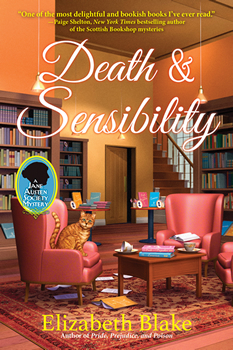

Death and Sensibility by Elizabeth Blake

Elizabeth Blake’s latest cozy mystery, DEATH AND SENSIBILITY, is set in the beautiful, historic English city of York.

In it, bookstore owner Erin Coleridge seeks the scoundrel who silenced a conference’s keynote speaker. Erin knows Barry Wolf didn’t die of a heart attack—he has no history of heart disease. So who did him in?

The suspects are many in Blake’s second installment of her Jane Austen Society mystery series. She talks more about Book 2—DEATH AND SENSIBILITY—in this The Big Thrill interview.

What do you like best about York? And have you ever gone hunting for the snickelways?

Wow, where to start? Like so many wonderful towns in the UK, history seeps from its very pores. Walking the cobblestone streets, you feel the thrill of centuries past, from the ancient people who first lived there to the Roman occupation through to the Vikings and England’s more recent history. You feel it the minute you enter the city—we came in through Micklegate, and I felt like I should have been astride a horse instead of in a rental car. I loved the winding streets of the Shambles, and York Minster was gorgeous. We went to a concert there, and the sound echoing from those ancient stones gives you chills. Walking the medieval city wall was utterly thrilling. The coffee shop I wrote about in the book really exists and is the coolest place I’ve ever had coffee in my life.

We did see a lot of the Snickelways, but it wasn’t until after I left that I discovered the wonderful book about them, written by the man who actually coined the term!

You skillfully use the weather, which is totally a British obsession, and pets (which we’re also batty about) in setting the scene for the book. What’s most important in terms of capturing a location without endless paragraphs of description?

I’m delighted you keyed in on my own obsession with weather—I am a self-described weather geek. I once knew an Episcopalian minister who had his own weather station above his office. I was enthralled and envious. When I lived in a rustic cabin at Byrdcliffe Art Colony in Woodstock, there was no internet—I had nothing but an old VCR. I got a video from the library, Twenty Most Amazing Tornadoes. I watched it twice. I would have watched a third time, but my VCR broke.

I love writing description, although I try to condense it to the essentials by reworking it over and over. It’s not uncommon for me to rewrite a descriptive passage a dozen times or more. I’m always looking to streamline or, in E. B. White’s famous dictum, “Omit needless words.”

Being one of those clever folks who writes for both stage and page, do you find writing for the theater a help or hindrance for writing books?

I think writing for theater is a great way of honing your dialogue skills. In prose, we have description, inner monologue, sensory detail, and extended action sequences, but in theater you have to accomplish everything through dialogue and onstage action. Screenplays are an even better form of discipline, because everything has to be so taut and condensed. I’ve written a few screenplays, which I think helped me enormously to develop this skill.

When I first started out, too often I would resort to “place-holding” dialogue—it did the trick, but wasn’t really special. The more I taught writing, the more I realized my own dialogue could be better. I tried harder to follow the advice I gave my students—that dialogue should either advance the plot, reveal character, or get a laugh. Ideally, it should do all three. So now I scour my own dialogue over and over, looking for “place-holders.” Then I either rewrite them or eliminate them.

I’m often asked about balancing the love storyline with the mystery one. Are there any tips for aspiring writers in the genre?

That is such a great question! On some level, it’s probably a matter of taste. I like a bit of romance, but I don’t want it to take over the story, so I tend to keep it more in the background, using it to twist the main storyline if possible. So my advice would be to try to intertwine the romance subplot with the mystery plot, rather than making them two parallel running stories.

I also think in a cozy mystery, readers expect some romance, but in moderation. I’ve kept Erin’s involvement with Peter Hemming pretty minimal, but at the end of this book it’s clear she’s falling for him, and vice versa. In later books in the series, the romance might have a more prominent role. But you don’t want the pair to get too comfortable with each other, or the tension drains out of the narrative.

I call that the Niles Crane Effect. In the American sitcom Frasier, Frasier’s brother Niles had a major crush on Daphne, their father’s physical therapist. It was a wonderful source of story tension and comedy. But as soon as he and Daphne got together, that whole vein of humor was lost. Romance is a wonderful source of conflict, but once the lovers get together, you have to find conflict within their relationship. Before that, the question of “Will they or won’t they?” is a natural source of story tension. The “prelude” to the kiss is always more enticing than the kiss itself. Jane Austen knew this and teased out the romance between Elizabeth and Darcy as long as she possibly could.

There’s also a real art in putting in enough clues for the reader, but also sufficient red herrings for them to feel they’ve a challenge on their hands. How best to do that?

Another great question! I try to have at least one clue and/or red herring per chapter, sometimes more. And, of course, every suspect needs at least one or two red herrings. A good way to camouflage a clue is to pair it with an even splashier red herring to draw the reader’s attention away from the clue. I learned that in the only writing class I ever took, a mystery writing class my friend Marvin Kaye taught at NYU.

What’s Erin’s strongest (and best) trait, and what’s her weakness?

My best friend has a theory that every personality trait has an adaptive side and a dark side—so the same trait can work for or against you, depending on the circumstances.

Like any protagonist worth her salt, Erin is strong-willed and inquisitive. The flip side of that is that she can be arrogant and nosy. She is loyal and brave, but her loyalty causes her to overlook certain things she should have noticed, and her courage can manifest as recklessness, which gets her into trouble.

Peter Hemming’s bad puns are as excruciating as Jack Aubrey’s mixed metaphors. Did you make them up yourself or did you squirrel away ones you heard? And is this detective based on a real person?

Thank you so much for saying they’re excruciating. Seriously, I consider that a compliment. It also raises the question of whether there’s such a thing as a good pun. I’m afraid I made them up myself. I’m not normally a punster, so I had to work really hard to come up with them.

Hemming is not based on anyone, though I do have a good friend who is a notorious punster: otherwise, he is nothing like Peter Hemming. My friend’s a gay lawyer who lives in Miami, loves early music, and speaks fluent Spanish (his husband is Colombian). He’s also handy with a hammer and a circular saw. I have a feeling Peter Hemming’s handyman skills don’t extend much beyond changing the occasional light bulb.

*****

Elizabeth Blake has written fifteen published novels, six novellas, and a dozen or so short stories and poems under other pseudonyms. Many of her works appear in translation internationally. Winner of both the Euphoria Poetry Competition and the Eve of St. Agnes Poetry Award, she is a two-time Pushcart Poetry Prize nominee and first prize winner of the Maxim Mazumdar Playwriting Competition, the Chronogram Literary Fiction Prize, Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Award, and the Jean Paiva Memorial Fiction Award. She was a finalist in the McClaren, MSU, and Henrico Playwriting Competitions. She is a Hawthornden Fellow and Writer in Residence at Bydcliffe, Lacawac, and Karun Colonies.

To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.

- The Deception by Kim Taylor Blakemore - September 30, 2022

- Death In The Aegean by M.A. Monnin - May 31, 2022

- Bad Blood Sisters by Saralyn Richard - February 28, 2022