Between The Lines Between the Lines: Clay McLeod Chapman

Let’s Get Haunted

There are numerous takeaways from Clay McLeod Chapman’s outstanding new novel GHOST EATERS, but here’s the big one: If someone offers you a drug that will allow you to see and interact with the dead, just say no.

Erin Hill would have done well to heed that advice, but healthy decisions have never been Erin’s strong suit. Several years out of college, she’s stuck in her hometown of Richmond, Virginia, adrift in every way that matters and dependent on her wealthy parents for financial support. She’s still in thrall to her on-again, off-again college boyfriend Silas, whose drug use has become increasingly unhealthy. When Silas fatally overdoses shortly after Erin stumbles through an attempted intervention, she’s consumed by grief and guilt.

In other words, she’s a perfect customer for Ghost, a new, underground drug that promises users the ability to contact their dead loved ones. But if Silas was a powerful presence in life, he’s even harder to resist in death. Erin soon finds herself addicted to Ghost, desperate to reconnect with Silas even if it means being terrorized by hungry spirits everywhere she goes.

The general outlines of GHOST EATERS are sketched by early 20th century horror literature—there’s a stellar nod to M. R. James’s classic ghost story “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”—but the colors that make it pop are straight out of the bizarro fiction palette. Ghost tongues loll from forever-gaping throat wounds. A faceless infant scurries through the walls of a half-built house. Deeply unpleasant things happen to eyeballs.

But for all its cringe-inducing body horror and hallucinatory set pieces, GHOST EATERS is a nuanced, heartfelt story about addiction, grief, loss, and regret. We’re not saying Chapman has gone soft (remember the eyeballs), but GHOST EATERS is as humane as it is horrific—which is another way of saying it’s Chapman doing what Chapman does best.

The Big Thrill recently spoke with him about the winding roots of GHOST EATERS, his upcoming Netflix collaboration with Jordan Peele (Get Out; Nope) and stop-motion legend Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas, Coraline) and what it truly means to be haunted.

Can you trace GHOST EATERS to any specific spark or starting point?

I feel like I need to acknowledge a few major sparks for GHOST EATERS… I’ll map out three.

First and foremost, back in… oh, say, 2017, I was tapped by a film production company to develop a feature in-and-around the idea of a “haunted drug.” That was it. Two words. Haunted drug. What if there was some flashy designer drug that had been developed in a lab—DEK73 or something lab-born like that—that had an unintended side effect of tapping into the hereafter? The production company was gunning for a Freddy Kreuger-style character stalking a group of teens who drop this phantasmagorical pharmaceutical at a rock concert and… well, the project simply fizzled like a lot of misguided feature films in development do. But I just couldn’t get those two words out of my head: haunted drug. Haunted. Drug. The concept really stuck in my craw, and I needed to claw it out, somehow. There was a story somewhere rooted around those two words, and I just had to find it… like I was foraging for mushrooms.

I needed to ground the story in something that mattered to me. Something I could emotionally connect to. Years ago, I lost a close friend to addiction, and the more I thought about that loss, the more the story simply seemed to… coalesce around this moment. I drew a line and called it tough love, but really it was simply me hiding from him when he needed me the most. I’ve never forgiven myself for that. Abandoning him. It’s amazing when you start to interrogate yourself about your personal failings as a friend and ask yourself, genuinely ask, what are your truest regrets in life, your biggest moral failings as a human being… This was certainly up there for me. So I wrote about it. Not exorcised the regret but accosted it. There’s no atonement here for me. This isn’t Flatliners. He’s still gone, and nothing I write will ever bring him back.

The last thing I want to bring up is I read Rachel Harrison’s The Return and… I don’t know. It just floored me. Her characters. Her voice. Something about Rachel’s writing inspired me to write my own book. I wanted to try and do what she did. I can’t hold a candle to her book, but still.

Something about the intersection of these three things led to the genesis of GHOST EATERS.

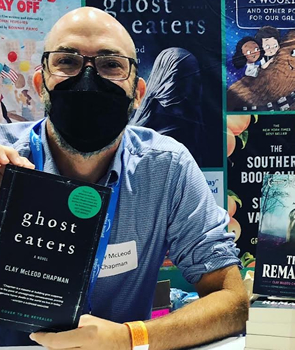

Chapman at San Diego Comic Con (SDCC) with panel moderator Maryelizabeth Yturralde, Kiersten White (Hide), and Anne Heltzel (Just Like Mother)

The characters of GHOST EATERS are haunted by literal ghosts (the people they’ve lost and can’t let go of) but also by figurative ones: the collective transgressions of the American South, from colonialism to enslavement to Jim Crow. Would this have been a dramatically different story if it had been set anywhere but Richmond?

When we were in the drafting process of GHOST EATERS, the hauntings were a little bit more… siloed, I guess you could say. Much like within spiritualism and séances of the day, there was something so… so privileged about the ghosts I wanted to write about. They were nondescript. Stripped of any identity. White, basically. But it got me and my editor talking about the core concept of the novel and the drug itself… and that conversation really cracked the book wide open: How presumptuous are the living to believe that they can simply reach out to the great beyond and contact their lost loved one when, in truth, there are unfathomable numbers of spirits lost on the other side, just waiting for their chance to speak or be seen. How could any spiritual medium link to that one single individual when there’s bound to be lord-knows-how-many ghosts clamoring for contact…

Look, America is one haunted piece of property. Look at what we’ve done on this soil. Look at the trauma, the bloodshed, soaked into the very soil. Especially Virginia! You can’t set foot into [Richmond] without stepping on someone’s grave. Now… take a drug that allows you to “see” those spirits bound to a particular locale and, well, you’re bound to see a hell of a lot. More than these characters bargained for. Which gets to that sense of privilege: It’s so damn easy for people to look the other way. To not address the poverty, the pain, the racism right in front of them. Ghost—the “haunted drug” in this book—becomes the great equalizer. Now we’re forced to see what’s right in front of us, no matter what. We can’t turn our heads. We can’t look away.

But, yeah, anyone who’s naïve enough to dose on Ghost in Richmond, Virginia, of all places is out of their damned minds. Where would the least-haunted spot to have a good trip even be?

GHOST EATERS is an entirely standalone novel, but in some ways, it feels like a thematic follow-up to The Remaking. That novel explored the evolution of a ghost story through multiple mediums. In GHOST EATERS, you present the ghost story as an addiction that spreads through a community. How have your ideas about ghosts and ghost stories evolved between those books?

Storytelling—specifically the oral tradition—is going to have a root in everything I write. It’s just what I love. Telling ghost stories, spinning yarns. Hell, even Whisper Down the Lane—which was about a fib that takes on a life of its own and leads to the satanic panic—is about storytelling in its own abstract way. If my ideas on ghosts have evolved at all between books, it’s almost in how they stubbornly remain the same: I always go back to that campfire. I always begin with an audience, a story, and a storyteller. That’s where our ghosts begin. Mine, at least.

What might’ve evolved is the idea of the listener… Who’s actually being haunted here? With GHOST EATERS, I wanted to actively ask both myself and the reader: What is it like to be haunted? It’s such a stoner-style question, but I felt like there was something to be explored in that simple query… What if, instead of our houses, we are the vessels for these spirits to roam? That gets to grief, gets to addiction, gets to all these grand themes I wanted to explore in the book.

Your ghost fiction feels like an active dialogue with centuries, if not millennia, of ghost stories. What is it that you’re trying to figure out?

Well, when you put it like that… it almost sounds like I’m trying to figure out if there really is an afterlife or not. Perhaps I’m trying to prove the existence of ghosts? Or whether or not I believe in them? Wouldn’t that be wild?

Or maybe it’s more poking at the raw nerve of what frightens me. Death frightens me. Ghost stories tend to actively tap that fear. It’s like a loose tooth that you just can’t stop prodding with your tongue, worrying the nerve underneath. With GHOST EATERS, maybe I’m just using my tongue to push-push-push at that loose tooth until the nerve itself snaps, drawing blood, and uproots itself once and for all.

In GHOST EATERS, ignoring spirits is a bad idea, but embracing them doesn’t work out so well either. What the hell do you want me to do if I encounter a ghost, Clay?

Ha! GHOST EATERS is just one big PSA for séancing! “Just say no, kids!” My first reaction was to recite the “Choose life…” mono from Trainspotting. I don’t know if that’s the answer I want to go with, but that’s what first came to mind… and I think our protagonist reaches a vaguely similar realization at the end of GHOST EATERS. Choose life over death. No ghosts, no Ghost.

I think a lot of the ghosts in GHOST EATERS just want to be seen… They’ve been marginalized and ostracized for so long that the simple notion of someone on the living-side of things seeing them for the first time in decades, centuries, is so… so… wondrous to them. Someone’s paying attention! But the dead want what the living have: Life. So… yeah. It’s a toughie. Just. Say. NO.

Mushrooms have long been a popular horror trope, but it seems like they’re everywhere now, from Fear Street to Mexican Gothic to What Moves the Dead. You’re as much a scholar of horror as a writer of it, so I’m curious about what you think might have gotten the portabella rolling for this latest cycle.

Mexican Gothic, definitely. I mean, come on. That book is amazing. How could we not all bow down to Silvia Moreno-Garcia? But I do believe fungal fiction—or sporror, as it were—has always been here, lingering under the surface of our skins, waiting for its moment to burst out.

There’ve been minor outcroppings… Remember that one episode in Hannibal? Amazing stuff. Jeff Vandermeer? Amazing, amazing. Sorrowland. The Wanderers. The Girl with All the Gifts. The Beauty. So many wonderful sporror books! The Last of Us? So much! Sporror, everywhere!

Switching gears a little, how did you get involved with Henry Selick and Wendell & Wild?

It was Jordan, as a matter of fact. I owe it all to him. We had dinner back in 2015, just as The Boy had its limited theatrical release, and we talked about what we were working on… He had this little indie, I dunno, he was working on… what was it called again? Oh, yeah—Get Out. I was just finishing up this trilogy of middle-grade action/horror novels I wrote for Disney, which I guess must’ve planted a seed, because a few months later… I got the call about Wendell & Wild.

So Jordan came onboard before Get Out hit theaters—in other words, before we knew. What made you realize he was exactly the guy you want to work with on a project like Wendell & Wild?

He is an honest person. He is honest with himself. He is honest to his collaborators. He speaks to a certain truth that gets the best out of the people he works with. It lifts the material to a higher level because it comes from a sincere place. These are the stories we’re dying to tell…

Since this interview will appear in our October issue, can you please suggest five under-the-radar horror novels that should be in our readers’ TBR pile?

The Hollow Kind by Andy Davidson. The Ghost that Ate Us by Daniel Kraus. White Horse by Erika T. Wurth. The Thing Between Us by Gus Moreno. Such Sharp Teeth by Rachel Harrison.

What’s next for you?

Well… a few exciting things are simmering right now. There’s a podcasty thing that is about to get announced, but I can’t say just yet. But let’s just say it’s going to be very, very spooooky.

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022