Features Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix

Closing Costs

If you know anything at all about the publishing world, it’s probably this: It’s full of people who think you should have to choose between a nuanced, deeply moving tale of grief and family strife, and a barnburner of a horror yarn about evil puppets who gleefully ram sewing needles into the nearest unguarded eyeball.

Readers, it’s a false dilemma. Grady Hendrix is here to tell you that you can have both.

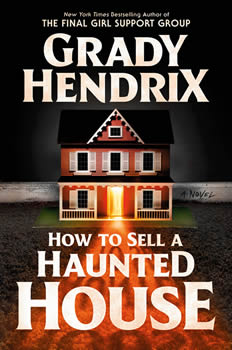

Hendrix’s latest novel (coming on the heels of his instant New York Times bestseller, The Final Girl Support Group) is HOW TO SELL A HAUNTED HOUSE, about a pair of emphatically estranged siblings who must sort out their run-of-the-mill issues to tackle a bigger one: Their parents have died under unusual circumstances, and the house they left behind is far from empty. Sure, there’s the matter of the hundreds of dolls, puppets, and decaying taxidermied animals that Louise and Mark Joyner’s mother spent her life collecting and constructing. But the real problem is the terrifying entity that has taken over the house in the form of Pupkin, a clownish hand puppet that was a fixture of the Joyner kids’ childhoods. Without their mother to dote on him and unable to accept the fact of her death, Pupkin becomes unhinged.

Meanwhile, Mark schemes to cheat Louise out of her half of the estate, and Louise isn’t having it. She’s a single mom and the money would be a boon for her and her five-year-old daughter, so Louise digs in and stakes her claim, murder puppets be damned. What follows is the trifecta Hendrix fans have come to expect: cringe-inducing horror, laugh-out-loud humor, and heart-tugging poignancy.

HOW TO SELL A HAUNTED HOUSE delivers in every way on its premise—if you’re strange enough to not be bothered by puppets and dolls, Hendrix will fix that (and he’ll make you look askance at squirrels while he’s at it). But the glistening, ever-beating heart of horror isn’t sadism; it’s empathy, and this is where Hendrix’s true mastery lies. He can write scares and extended action beats with the best of them, but it all works because his characters are finely drawn and fully realized. In the end—evil puppets, neighborhood vampires, or deranged slashers aside—they’re dealing with the things most of us will face: growing up, navigating the endless trials of adulthood, and losing the people who, if we were lucky, guided us through it all.

In his latest interview with The Big Thrill, Hendrix talks about the inspiration for his new novel, the economic subtext of haunted house stories, and his next, disturbingly relevant horror outing.

Can you trace the beginnings of HOW TO SELL A HAUNTED HOUSE to any specific moment or inspiration?

Standing in my mom’s garage during the pandemic and staring at three bags of fabric scraps she’s keeping to make a quilt. I’d gone down to South Carolina because she was having a health emergency, and I went into the garage to get something and just saw all this stuff she’d saved over the years, including the three bags of fabric for a quilt. My mom has never made a quilt. She is never going to make a quilt. And one day she will die, and I’ll have to throw out these bags of scrap fabric for her imaginary quilt, and that’s going to be hard. I can’t save them because they’re not a family heirloom, but throwing them out is going to feel like throwing out a little piece of her. And I realized that’s what we’re all going to have to do one day: go through our childhood homes and throw away the stuff our parents left behind. And what are ghosts besides something our ancestors left behind?

In a previous life, you worked for a parapsychology research group. Did that experience inform this book at all?

Actual parapsychology is deeply undramatic. It’s a lot of lab work, a lot of site visits to places where nothing happens, and when you do record people’s actual experiences, you realize that while they are often enormously important to them, they sound pretty banal to everyone else: They saw their grandmother walk down the hall, they heard someone call their name in an empty house, they felt a presence for a few seconds. Not the stuff of Big Bloody Horror.

What it did tell me, though, is that so many people have experiences like this, and they are profoundly emotional for them. It taught me that you can’t have horror without talking about the deepest emotional experiences we have: our thoughts surrounding death and loss and love and guilt and our perceptions of reality. Because let’s face it: If we as a society saw an objective, inarguable ghost, then everything we know about religion and science would change in a heartbeat. Horror has high stakes baked in. We don’t need walls weeping blood or swarms of flies to deliver it.

I feel like this book, more than anything else you’ve written, leans into Paperbacks from Hell territory; it feels very much informed by ’70s and ’80s horror literature. What are some books that were on your mind while you were writing it?

Most of what I was thinking about when I wrote H2SHH were 19th century ghost stories because I wanted this to be a classic haunted house book full of cold spots and doors that open and close by themselves, stories within the story, which was a traditional feature of 19th century ghost stories, and lots of family secrets. I was also reading a lot of Kenneth Gross at the time. He’s written several books and edited several others about puppets, dolls, and our relationship with them. As Maria Tatar is to fairy tales, Gross is to puppets and dolls. Highly recommended.

The horrors Louise and Mark face are intensely personal—the house in question is the one they grew up in, and what happens to them in that house is deeply tied to their own histories. Haunted house stories often involve people dealing with the trauma of strangers—they move into a house and are haunted by a previous family’s baggage. Was that history on your mind while you were writing HOW TO SELL A HAUNTED HOUSE?

I wrote H2SHH during the pandemic when I was separated from my family and I wanted to immerse myself in an imaginary family, which meant I had to write a haunted house book because they’re always about family — the things they hide, the stories they tell, their secrets, their curses, their legacies. You’re right that haunted house stories are often about encountering a stranger’s phantasmal family, or at least its ectoplasmic remnants, but books like The Shining or The House Next Door or The Haunting of Hill House are also about people dealing with the disintegration of their own families.

Haunted house stories are often tied to economic hardship or stress. Is that just a function of the plot—a way to get people to stay in a house that’s obviously not an okay place to be—or is there something deeper at work there?

One of the worst misfortunes we can imagine is becoming homeless. We long for a roof over our heads. We scrimp and save to buy our houses. We get wiped out financially and, even more importantly, emotionally when our houses are robbed or they burn down. Our house is our fortress, it’s our safe space, it’s our foothold on the economic ladder. It matters to us enormously, both financially and socially and psychically. So when a house becomes haunted, it cuts right through our defenses and hits us in our weak points. Sure, haunted house books often tie in the economic stress with emotional stress because the more pressure you can put on your characters the better, and while that’s in part a function of plot, it’s also a tradition that goes back to Margaret Riddell in the 1870s who wrote books like The Uninhabited House which yoked land speculation, bankruptcy, and social climbing together under stories about people investigating haunted houses.

One thing (of many) that delights me about your novels is that they haven’t really changed since you landed on the New York Times bestseller list and made the jump to a major publisher. Are you ever surprised by the broad appeal of your work?

I’m deeply surprised and deeply grateful that anyone wants to read what I write at all. I just try to reflect the world I see around me in my books, and it’s been an amazing feeling to see that weird point of view resonates with anyone. What’s wrong with them???

This is looking back a bit, but how did you make the jump from freelance film writing to writing Horrorstör for Quirk?

I went to Clarion Writer’s Workshop in 2009, and that changed everything. There were no more freelance writer jobs thanks to the 2008 economic crisis, so I decided to get serious and apply to Clarion. It made me step up my game and take what I was doing seriously. It showed me how far ahead all these other, mostly younger, writers were, how much better read they were than I was, and it introduced me to people who were doing what I wanted to do. It was connections I made there that led, through an enormously circuitous route, to writing Horrorstör at Quirk. And by the time I wrote Horrorstör, I had co-written three books, self-published two, and had a third in my drawer. So between going to Clarion and my sad and sick compulsive writing tendencies, I somehow landed that with Horrorstör, despite the fact that my editor at Quirk, Jason Rekulak, had serious doubts about me.

Can you tell us anything about what you’re working on now?

I’m writing a kind of Rosemary’s Baby set in a home for unwed mothers in 1970. I started working on it well before the Dobbs decision, and it’s been wild to watch what I felt was an obscure little corner of history become more relevant than ever.

Ed. Note: To promote the book, Hendrix is embarking on a nationwide tour of a one-man show called How to Sell a Haunted House in a Challenging Market. If you’re familiar with Hendrix’s live performances, you can probably guess it’s not so much a book signing as a whirlwind tour through the centuries-long history of haunted house stories. (Though he’ll sign your book, too.) He’s staging the show live at venues around the country, but Barnes & Noble is hosting a one-time, free virtual performance on January 17.

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022