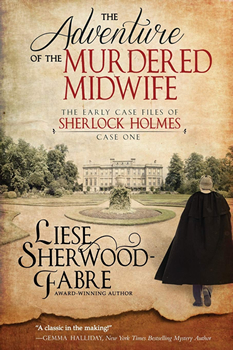

The Adventure of the Murdered Midwife by Liese Sherwood-Fabre

In THE ADVENTURE OF THE MURDERED MIDWIFE, only weeks into his first year at Eton, Sherlock’s father calls him and his brother back to Underbyrne, the ancestral estate. The village midwife has been found with a pitchfork in her back in the estate’s garden, and Mrs. Holmes has been accused of the murder.

Can Sherlock find the true killer in time to save his mother from the gallows?

In this The Big Thrill interview, author Liese Sherwood-Fabre shares insight as to what she loves about Sherlock Holmes, and why she was drawn to him for this novel.

Holmes remains a popular character and one who provokes a lot of loyalty amongst readers. What implications does this have for a writer who is tackling him today?

A few years ago, I participated on a panel at the 22lB Con on alternate universe Sherlock Holmes. I’d written such a story for an anthology. In my story, Curious Incidents: More Improbable Adventures, Sherlock is a vampire in a world of vampires, and someone is killing them—not easy when you’re dealing with the undead. Other panelists had the Sherlock character as a cyborg, genderqueer, a woman, etc. Despite such diversity, something basic in the character still provides the “essence” of the original Sherlock Holmes. Fresh, yet familiar.

In A Study in Scarlet, Watson lists 12 limits to Sherlock’s knowledge. While they don’t all necessarily have to be reflected in a character, there must be something that rings true to parts of the list. While not appearing in Watson’s original list, I think the most important is the logical process he uses in his investigations, and the insightful way he weaves disparate pieces of information and observations into the right conclusion.

When I crafted my young Sherlock, I had to ensure this character was not too different from the one in the original tales, but I did have some leeway, given his age. He hadn’t developed all his skills, but they had to be there in incipient form. He had to be evolving—both intellectually as well as physically and emotionally—into the man he would become.

The gaps and unanswered questions in the Holmes canon are both renowned and intriguing. Do you have a secret theory about part of Holmes’s—or Watson’s—life that you could share with us?

I became intrigued with the question of how Sherlock Holmes became the detective Sir Arthur Conan Doyle described, given that Conan Doyle provided very little about his character’s origins. In one story, Holmes shares that his ancestors were country squires and his grandmother was the sister of Vernet, the French artist. That information, along with having a brother named Mycroft, represented almost all his history. It also offered a basically blank slate to create a series about his early years.

One of the “rules” of writing is to do the unexpected. A conventional answer might have been that his father or some other male mentor played a major role in his education; I decided to make his mother the one who shaped his development. This aligns with Victorian society. Until boys were sent to boarding school, the mother was in charge of all her children’s education—arranging for tutors, governesses, and the like.

At the same time, Sherlock’s mother had to be unconventional. Because he and his brother had to get their superior intelligence from someone, I decided it would be her. At the same time, Victorian restrictions limited how much education she could pursue—although I did have her obtain some medical education in France. In keeping with Victorian conventions and her own unconventionality, I created a mother who viewed part of her duties as developing her children’s intelligence. Sherlock is always having something to learn and his mother is usually the one he seeks out for advice.

You’re clearly as fascinated as I am by life in Victorian England. What was the most surprising thing you discovered in your research?

I think the most surprising thing I’ve discovered was the evolution of the role of women within the society, as reflected in some of the original stories. Especially in the later ones, we are presented with women who had careers, such as governesses and typists. One even rode a bicycle, a true expression of independence and freedom at that time. Sadly, they all needed a man to save them in some way, but still they were out there making their own money to pay his fee.

Is Underbyrne, the Holmes residence, based on a real house?

I knew that Sherlock’s ancestors were country squires, and as such they would have to have an appropriate ancestral home. Searching for “country squire homes” didn’t really provide me with any good examples except for some that would be more like manor houses (one step down from Downton Abbey-size). These were larger and more prosperous than I wanted for this family. On one search, I found a photo of one of Conan Doyle’s houses. That provided me with an image of a home similar to what I imagined for the Holmes family.

What’s the influence behind Uncle Ernest, who positively leaps off the page?

Thanks for the endorsement of Uncle Ernest. I did have fun creating him. When I considered what sorts of mentors young Sherlock might have in addition to his mother, I thought an inventor-type would provide another facet of instruction—his own special Q-Branch a la James Bond—but with an “absent-minded professor” air about him, like Doc Brown from the Back to the Future series. To provide an explanation of why this bachelor uncle lived with the family and his quirky personality, I gave him PTSD—although it wasn’t something that was identified in the early 1800s. To explain the PTSD, I made him a soldier sent to India—not an uncommon occurrence back then. Even Watson spent time there.

Balancing the needs of a modern-day, maybe US-based reader and a historical, English-based story is a bit of a juggling act. How do you reconcile the two and what choices have you had to make in terms of vocabulary?

Several famous authors and statesmen have been attributed to a saying that the US and Britain are two countries separated by a common language. For the most part, I write US English because I’m not really adept at the other. I did include references to gaol, instead of jail—but that’s about it.

What’s more fun to me are the slang and everyday items common during Victorian times that are no longer in use today. I will sometimes put in a filler modern equivalent saying/term, and then go back and find something that would have been used at that time. A Victorian would know the difference between a Hansom and a Clarence carriage, but most modern readers wouldn’t. When I use such language, I believe it is important to provide enough information for the reader to know what it means. It is similar to using foreign terms in a story.

Perhaps the most important technique to make the story feel more “authentic” is the narrator’s voice. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the stories—for the most part—from Watson’s point of view in a conversational style with contractions and a lot of dialogue. Where I differ from this style is the more modern emphasis on the characters’ emotional aspects. Otherwise, the tale would just be a reporting of what happened, and that makes for a very dry story for modern readers.

*****

Liese Sherwood-Fabre was born in Texas and knew she was destined to write when she got an “A” in the second grade for her story about Dick, Jane, and Sally’s ruined picnic.

For several years, she focused her talents on professional writing, earning a PhD in sociology from Indiana University and working on various policy and research projects for the federal government for 30 years. After 10 years abroad in this capacity (serving in Honduras, Mexico, and Russia), she returned to her native Texas with her family.

She has been writing for about 20 years and garnered a number of awards, including a Pushcart Prize nomination. Steve Berry described her debut novel Saving Hope as “a tantalizing premise that toys with the most basic of emotions—a parent’s drive to save their child.”

Most recently, she has turned a childhood interest in Sherlock Holmes into a series of novels relating to the previously unknown story of his development into the world’s greatest consulting detective. Her research essays into Sherlock and Victorian England are published across the globe and have appeared in the Baker Street Journal, the premiere publication of the Baker Street Irregulars.

To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.

- The Deception by Kim Taylor Blakemore - September 30, 2022

- Death In The Aegean by M.A. Monnin - May 31, 2022

- Bad Blood Sisters by Saralyn Richard - February 28, 2022