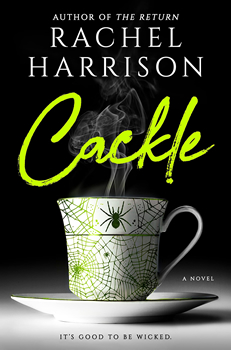

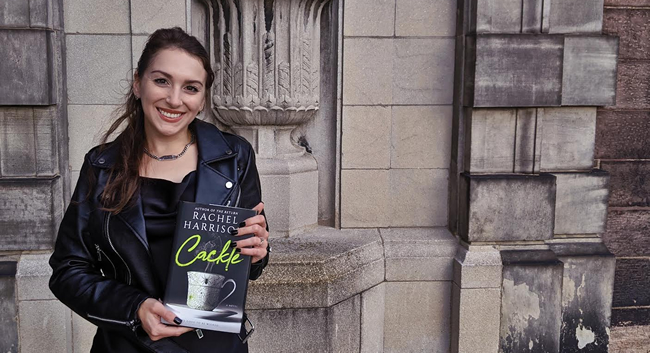

On the Cover: Rachel Harrison

When Life Is ‘a Romcom of Horror’

Rachel Harrison announced herself as a formidable new voice in horror with her 2020 debut The Return, a frightening and sometimes funny story about female friendship that slowly morphs into hair-raising body horror. Her follow-up, CACKLE, is both a marked departure and unmistakably a product of the same author. CACKLE doesn’t lean into gore and traditional scares, but it’s full of the wit, insight, and classic horror trappings that made The Return such a twisted delight.

Like The Return, CACKLE centers on a young woman who’s been dislodged from her previous, comfortable life. Annie Crane has recently been dumped by the man she thought she’d marry, and she flees New York City for a fresh start in a charming upstate town. As she settles into Rowan, New York, to teach at the local high school, Annie finds herself drawn into the orbit of Sophie, a glamorous, wealthy older woman who seems to hold the entire town in thrall. As Annie and Sophie’s friendship veers into a strange codependency, it becomes clear that Sophie isn’t what she seems—but, perhaps, neither is Annie.

If ever a book was crafted for October reading, CACKLE is it. Charming and creepy by turns and shot through with equal parts humor and dread, CACKLE has the feel of a beloved Halloween special that suddenly grows spider legs and needle fangs.

In her first interview with The Big Thrill, Harrison talks about her path to publication, how folk horror influenced her new release, and why she set out to write about witches in the first place.

I think I liked CACKLE even more than The Return. They’re very different, though, wouldn’t you say?

Yeah, they are. I’m a little nervous. I’m glad you say that, because the weeks leading up to launch are so vulnerable for a writer. I’m a little bit like Annie, and I’m very anxious. I’m curious to see how people will respond to CACKLE, because it is different. But I think it was important for me to write a different book, because I don’t want to write two [similar books] back-to-back. You might get stuck in a place where your readers expect a certain thing. I wanted to have freedom, moving forward, to kind of play around and do different things. I think the voice will always be the same, because it’s always going to be me writing it. But I want readers to know they can expect something different and surprising of each book.

When I first saw the announcement about your second book, I remember thinking, Of course it’s about witches. Of course it is. But CACKLE is nothing like what I expected. I went in knowing very little, and I’m glad I did; I had a hard time figuring out where it was going. Do you think it’s a horror novel?

I think there’s a lot of dread. Because I’m somebody who has an anxious personality, dread is really what gets me and makes me feel afraid. Louder, slasher horror—that stuff scares me too, but it doesn’t get under my skin the way dread does. I think there are some pretty powerful moments of dread in CACKLE, and I did want to build a sense of dread and have readers not know where it’s going. For anybody who’s a type-A planner like me, not knowing where something ends up is terrifying.

CACKLE is not loud horror, but I think horror can be many different things. And we’re seeing a lot of exciting things happening in the genre right now, where there’s just such a wide range of places that people are going and what they’re playing with and tropes and conventions and how they’re unraveling those. I think CACKLE is part of that conversation. I do think readers should go in knowing that it’s going to be different than The Return. And it might not be the kind of horror that they may expect having read The Return, but I do consider it horror.

Some of the things that were the creepiest to me were not the obvious things. Early in the book, there’s a scene where Annie is walking through this really charming farmers’ market, and everyone is so nice and it’s a beautiful, sunny day. As someone who watches and reads a lot of folk horror, that scene struck me as so foreboding. I feel like CACKLE kind of lives in the shadow of folk horror, which is a high compliment. Were you thinking about that when you were writing it?

I think what really kind of kickstarted me thinking about CACKLE—and my original concept was different and kind of transformed into this—was when I saw Midsommar. I went in without any expectations or spoilers, and I just had such an incredible experience watching that movie. I loved how I didn’t know where it was going. I loved the feeling it gave me. I loved that it was bright—I think it was such a clever idea to make a horror movie where, if you turn the sound off and came in in the middle of it, you wouldn’t know you’re watching a horror movie. That inspired me and got me thinking, and I really have a love and appreciation for folk horror.

Also, I grew up drinking the fairytale Kool-Aid. I was a kid in the ’90s, so I grew up on Beauty and the Beast, all of the Disney fairy tales. As I got older and more jaded, I kind of had a love-hate relationship with those fairy tales. And so those things were all in my mind when I set out to write CACKLE.

How did the experience of writing CACKLE compare to writing The Return? A lot changed for you between the two books.

It was different, because when I wrote The Return, I didn’t have an agent. I didn’t have a publisher. It was just me alone on my couch, with hope but no expectation. And then when it came time, and they were asking, Do you have another book? I’m like, Sure! And then I got 30,000 words into a second book. I write pretty fast, so I had a month where I was like, Oh, I got something. And then I was like, Nope, don’t got it. It was a false start. And then after I saw Midsommar, I had a boom of creativity, and I wrote an outline and sent it to my agent. And she said, There’s stuff here, but it’s not it. So I decided I couldn’t work from an outline and I started writing a draft. I got 30,000 words into that, and it wasn’t working but there was something there. When I started rewriting that draft, that’s what became CACKLE. So I think it was just kind of typical for me—because I write so fast, I can easily waste time taking off running, and then realize I’m going in the wrong direction and have to turn around and go back. Which panicked me a little bit, because now I have people who are waiting on something.

Let’s talk about Annie and Sophie—how did they take shape for you? And what did you enjoy most about writing them and their relationship?

I’m a little hesitant to admit how much Annie and I are similar. But Annie is very much a version of me—my anxiety and inner monologue can be very similar to Annie when I’m feeling vulnerable or self-deprecating. So she was very much a funhouse mirror image of me, in this kind of fantastical world. But I had a ton of fun writing her. All of the goofy thoughts that I have when something embarrassing happens to me, or when I’m feeling awkward in a social situation—I was able to take those things and give them to her. It was kind of like having a friend on the page. If she and I met in real life, once we got past the initial awkwardness, we would be really close.

As for Sophie, I was kind of a shy kid in middle school and high school, and I befriended a few older girls. When I was a freshman, I befriended a senior who was and probably still is the coolest person ever. She just kind of took me under her wing. When somebody who is older and self-assured can reach out a hand to somebody who might be trailing a little bit, I think there’s something so special and powerful about that. And so Sophie was inspired by all of the older women who took me under their wing.

So let’s talk about witches. I’m guessing you’re probably someone who has enjoyed witch stories for a long time. Would I be correct?

Yes—I think, again, because I grew up with fairytales. I started writing this book pretty much on my 30th birthday. We treat women differently as they get older—either you’re a young, beautiful ingenue, or you’re the undesirable old hag. I had this moment as I was moving out of my 20s, where I was like, I’m not the young ingenue anymore. Why do we have this dichotomy of either/or? And as I got older, I started to wonder, What’s wrong with a witch who lives in the woods and is fine being by herself? Why do we assume she eats children? Why do we vilify a woman who just wants to do her own thing? I wanted to explore the archetype of the witch—why was it created? And why is she scary?

Going back a little bit, can you tell me about your path to publication with The Return?

I’d written drafts of novels before, but The Return was the first one where I finished and had a good feeling about it. So I randomly did a Twitter pitch contest called PitDark. I took the day off work on a beautiful fall day in October, and I had my four pitches. I tweeted out my pitch, and the first one got a few likes. And then the second one started getting a lot of attention. I remember thinking, Is this happening? It was so surreal. I went for a walk—all the leaves were changing color and I had my pumpkin spice, was being very generic. And then all of a sudden, I was getting requests. And I thought, I have to run home and send out my manuscripts! So I met my agent through the Twitter pitch contest. She gave me some edits, and I took another day off work and worked all day on the edits. And then, within a month, we were out with a manuscript. It’s kind of an annoying story, because you don’t see the years of struggle behind it.

Yeah, “overnight successes” in publishing usually come after years of hard work and persistence.

And exploring different avenues. Because if I had said, Oh, this is a Twitter pitch contest, I should just go the traditional route of querying, I would have missed out on the opportunity. So I think being open-minded helps. For me, it was years of persistence, and then just being open and finding the right opportunity. It was kind of like this brilliant moment of luck.

Have you always been drawn to horror?

Yeah, I think I’ve always been obsessed with horror. You know in romcoms, where there’s the childhood best friends, and you know they’re gonna end up together, but they’re kind of reluctant? I feel like that’s me and horror—like my life is just a romcom of horror. I’ve always had a relationship with horror, but I couldn’t admit to myself that I loved it, because I’m afraid of everything. I have an early memory of seeing The Blair Witch Project. We had just moved into a new house in the woods, and we didn’t have window dressing. So I was maybe 11 or 12 years old, lying in bed, trying not to stare at the woods. It was torture! It was agony. So I was like, I don’t like horror. But it’s because it scared me and it affects me so deeply that I think I just needed to give myself permission to scratch the itch.

Some people think horror is a misogynistic genre, and others think it’s essentially a women’s space—that we’ve sort of been brainwashed into thinking male voices are the dominant ones in horror. What do you think?

I think horror is for everyone. We live in a patriarchal society, and a lot of horror is a product of the world we live in. I would like to think there are a lot of really amazing people working really hard to make this world a better place, even though a lot of it’s been very difficult and it seems very hopeless. But I think there are a lot of talented artists who are relentlessly pursuing art that matters and will make a difference. And out of that, there are a lot of incredible up-and-coming horror writers who are telling different stories, and I think there’s a lot of room in the genre for different stories. There are plenty of seats at the table, and I think we need to start pulling out chairs for everybody.

Why do you think horror literature seems to be booming right now?

It’s hard to say. At the beginning of the pandemic, I kind of thought, you know, it’s a safe place to feel your fear. The Return got picked up in 2018, it seemed like, Oh, well, Hill House just came out on Netflix, and this is going to be a trend. But it’s three years later, and I don’t think it’s a trend. Finally, more diverse voices are coming in, and hopefully we can still, as a community, build up more voices. It’s because of these new voices who’ve worked so hard to be here and to be heard that horror is finally connecting with everybody, instead of just feeling like a niche market.

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022