BookTrib Spotlight: David McCloskey

A Journey Through the Minefield

He was midway through a cup of booza, an elastic Levantine ice cream, and nursing a bottle of water when the mind games started. He’d executed the tradecraft perfectly, he thought. Or had he? Had the woman buying ice cream been the same woman from the jewelry store? Had the quick peripheral movement outside the pharmacy actually been a teenager kicking a soccer ball?….In the eerie silence, a crackle, maybe a radio, maybe a footfall on crumpled foil….

He felt hunted.

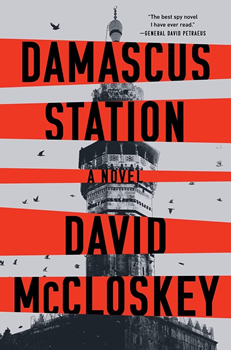

Sam Joseph is a CIA case officer, and a good one, but in David McCloskey’s DAMASCUS STATION, his time in Syria has taken a decided turn for the worse. The nation has descended into chaos, a steady succession of mortar volleys, suicide bombings, and daily atrocities. The two people he was sent to exfiltrate—a compromised asset and his handler—have both been captured. His attempts to find out what happened to them have led him not only into a perilous forbidden relationship with a Syrian Palace official named Mariam Haddad, but brought him to the attention of the men who run Syria’s security services: Ali Hassan, the country’s senior spy-catcher, and his older brother Rustum, head of the Republican Guard. The two hate each other, but their individual calculations for the way this war must go has no place for spies or traitors, and their efforts to eliminate both have escalated in ruthlessness.

The rebels are planning a spectacular last-ditch effort to turn the tide. The Mossad is getting restless. The Russians have been called in. Sam Joseph has a strategy, but since it includes withholding a lot of information from his own station chief, it’s beginning to seem questionable at best. Good tradecraft is important—but what if the other side’s is better?

DAMASCUS STATION is an extremely effective modern espionage novel, filled with action and incident, but also a profound knowledge of the people and factions of Syria, the complex maneuvers of spycraft, the gray areas and competing egos and overlapping priorities that make every day a journey through the minefield.

DAMASCUS STATION is an extremely effective modern espionage novel, filled with action and incident, but also a profound knowledge of the people and factions of Syria, the complex maneuvers of spycraft, the gray areas and competing egos and overlapping priorities that make every day a journey through the minefield.

It’s a dazzling debut, and comes from a place of great personal knowledge. McCloskey himself covered Syria as a CIA analyst from 2008 to 2014, living and working in field stations throughout the region and briefing officials in Washington.

“The seed for the novel,” he says, “goes back seven years, when I was leaving the Agency. I had been working on Syria and was struggling to process the tragedy and hopelessness of that conflict. So I started writing about it. To be honest, the copy from that period is aimless and florid, but it birthed the two primary Syrian characters in this book: Mariam Haddad and Ali Hassan. I think I wrote almost one hundred thousand words and eventually set it aside. Five years later, I picked it up again and decided it was awful. But this time I really did want to finish a coherent novel, so I was more structured about the plot and the character development.

“Ultimately, I was interested in telling an authentic story: one that described the actual CIA, its tradecraft and operations, and the real Syrian war. The story came to life as I wrote. Over time—and this was not obvious at the beginning, by the way—it became clear that the relationship between Sam and Mariam was this story’s emotional core. Their relationship provided a lens for the operations, the intrigue, and the civil war. The novel became their story.

“I wanted to write a spy novel in which the protagonist is a CIA case officer—not an assassin or in the Special Forces—so I created Sam as a composite of several people that I knew well at Langley. The job is fascinating: these men and women spend their days spotting, developing, and recruiting sources to spy against their governments. A case officer protagonist opens the door to action and suspense and intrigue, but because the centerpiece of the job is to recruit agents, there is an authentic emotional component that I think runs the gamut of the human experience. It’s certainly possible some of me ended up in Sam’s character—I mean, how could it not?—but I really tried to let the sketches of these real-life case officers be my guide.

“The most memorable set of moments for me were in the middle of the Syrian war, when I traveled around the region with a group of very senior Agency folks. I cannot share much about the trip, but it was one of those experiences in which, as a decently young person, I was given a peek behind the curtain of power. We sat down with some of the top people in a host of regional capitals. It was a masterclass in espionage and the way the Middle East really works. I’ll remember it for the rest of my life.”

He couldn’t depend entirely on his own experiences, though: “I did a lot of research. I knew Syria and the CIA, but once the Pandora’s Box of a novel has been opened, you realize there are thousands of things you need to know that you do not. Some are small and manageable to research in short periods of time. For example, what would a fashionable Syrian woman wear to a party in Paris, or on the French Riviera? What species of trees grow in northwestern Syria (I had visited, but I was not paying attention to this detail at the time)? These were not facts I had in my brain, but they also did not require an immense amount of effort. Some bigger topics demanded more study. The mechanics and emotion of surveillance detection routes and how to build a car bomb were probably the two most interesting.”

Other details jump out at the reader as well, and I had to ask him about a few of them. True or false?

- Sam has an assigned “funnyname,” Burt O. Goldjagger, an absurd-sounding alias to use in written cable traffic. Real CIA aliases are just as absurd. “True. The censors wouldn’t let me put the real-life ones in here, many of which are more insane than Sam’s.”

- The funnyname was generated by a computer program using a British phone book from the 1950s. “Not sure, actually. I’d heard this mentioned in the Langley rumor mill, but I think the truth may have been lost in the mists of the early Cold War.”

- “The bipolar nature of the Agency never ceased to amaze: CIA had the ability to find and kill a person in the remote Hindu Kush, and on the other hand, he couldn’t find a working stapler at Langley.” True(ish). There were sporadic shortages at Langley. I’d call this one mostly true.

- Sam tells Mariam about a handler who used a taxidermied cat as a dead drop. (“The agent would stuff papers and messages in a compartment that had once held intestines.”) Roadkill-based dead drops have been used.

- Live bomb tests have been used on cadavers wheeled out on rollerblades and suspended on IV poles. “Completely false. I had help creating my fictional bombs from a couple EOD techs, and when they read this part, they said, ‘This is totally insane, the US government would never do this.’ I said, I get it, but this is too fun to cut. I left it in.”

“I have a 9 to 5 mentality about the writing process,” McCloskey says. “When I’m working on a book, I sit down in front of a computer Monday through Friday and write like I’m punching a clock. I find that some days the words and ideas flow; other days, not so much. But it’s impossible to tell in advance which kind of day it is going to be, so you just have to do the work.

“Within that framework, I think about the whole thing as a dig site. There are no computers or scanners to see what’s below the ground. There is a patch of dirt. I believe this is Stephen King’s analogy, by the way, and I’m shamelessly stealing it. I first try to make sure I’m at the right site. This is the setting, the mood, the high-level arc, the main characters in the most general of terms. Not the plot. Not the chapters. But this is important to get right before I put words on a page. If you’re at the wrong dig site, nothing is going to work. Once I have that, I start shoveling out the earth by writing. Some days you dig out big clumps of dirt, and other days you find dinosaur bones, and still others you find you’ve wandered off the site entirely and have to come back. The process is frustrating and non-linear, but I have not found a way to write a book other than by experimenting to see what works.

As I write, I’m really rushing to get that first pass (or draft) done. I want to dig out as much earth as possible to see its general arc and shape. Then, on the second, third, and maybe even fourth passes, I’ll sharpen the plot, character motivations, and overall themes. That first draft is sloppy, but it’s something to react to.

“I’m an avid reader of the genre, and I am sure many of its leading lights have influenced me in some way: le Carré, McCarry, Deighton, Clancy, Greene, Cruz Smith, Higgins, Forsyth, the list could go on. More recently people like David Ignatius, Jason Matthews, Daniel Silva, and Alex Berenson come to mind. One aspect of the genre—though by no means important to every author writing in it—that has influenced my work is the tension between moral clarity and moral ambiguity permeating so much of the intelligence business. I love stories that have good guys and bad guys while at the same time entertaining the gray areas. I like the complexity and the ambiguity that come with the intrigue, and I hope to carry that through in my novels.”

His skill at finding that complexity helped him to his publisher, and so did a piece of luck: “My wife knew an agent through a colleague at her old think tank in DC. I told him I was working on a spy novel, and he was kind enough to counsel me on the plot and offered to read it along the way. We had just submitted the book to publishers in February 2020 which, it turns out, was a bad time. COVID hit, and for several months we heard crickets. Then, out of the blue, Star Lawrence at Norton called. He said he liked the story, but had a few things he wanted to work on. Most of the problems were Writing 101 mistakes I made because I’ve never taken a class on writing and I’m generally skeptical of books on how to write. Star helped me improve the prose and the story, and we worked together over the summer on the manuscript. When the process was done, he bought the book.”

I had one final question for McCloskey. During his time covering Syria, did his views about the country and the global response to the war change in any way?

“Writing the novel brought back some tough memories about this. The policy decisions facing the Obama administration in the early years of the war were tangled, and I certainly did not envy his foreign policy team in 2011-2013 when they were wrestling with how to handle this. That said, I think a fundamental mistake was to let our rhetoric outpace our political will or, frankly, our true capacity to affect change in Syria. In short, I think we let down our Syrian partners, provided space for Assad to consolidate control (with help from Iran, Hizballah, and Russia), and undermined US regional credibility in the process. There was a mistaken belief among some influential players in the Obama administration that Assad would eventually fall: Mubarak was gone, Ben Ali was gone, Gadhafi was gone (never mind we acted as the Libyan rebel air force), and Saleh in Yemen was tottering.

“To some (not to the CIA, for the record), Assad’s demise was a matter of when, not if. This was a mistake, possibly the original sin of the whole US approach. If you think he will inevitably fall, you can sit back and tell the world that Assad must ‘step aside’ and not really do much to back that up because he will be a goner soon anyhow. The truth is that the regime has been far more resilient than anyone could have imagined, willing to do anything to survive, and the US simply never had the political will to match.

“To bring this back to the novel, one of the sad realities is that Syria disintegrated as this global thumb-twiddling happened. And, of course, it was ordinary Syrian people who suffered most. The book is dedicated in part to the people of Syria. My hope is that readers walk away with some understanding of what it was like to live through the war, as well as an appreciation for the complexities of a conflict in which normal people took up arms on all sides, mostly out of the basic human desire to protect themselves and their families.”

McCloskey’s next book is another spy novel, centered on the next stage of the US-Russia spy war: “It’s not a sequel to DAMASCUS STATION, but it’s in the same universe, so some characters will reappear.”

It’s certain to be exciting—and just as essential.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- ITW Presents: The Breakout Series - April 25, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: DEATH UNFILTERED by Emmeline Duncan - April 25, 2024

- AudioFile Spotlight: Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks for April - April 25, 2024