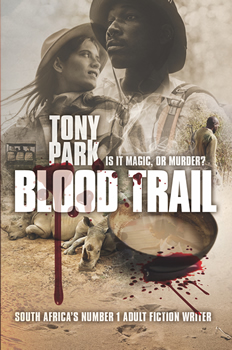

Africa Scene: Tony Park

Magic—or Murder?

BLOOD TRAIL is Tony Park’s terrific new thriller set at a private game reserve and a nearby rural village, Killarney, bordering the Kruger National Park. Mia, an expert tracker, and her partner, Bongani, are trying to keep Lion Plains private game reserve safe from poachers, but despite their dedication, they’re failing. Rhinos are being poached, and the poachers vanish apparently into thin air. Is black magic—muti—delivered by local sangomas (witch doctors) involved? Girls from Killarney village disappear. Then a boy who keeps reptiles and sells them to sangomas is murdered. Sannie van Rensburg from the South African police is doing her best with limited resources but making little progress. And that’s just the start.

Although an Australian, Tony Park is the author of 19 bestselling thrillers set in Africa. A “once-in-a-lifetime” safari holiday to southern Africa in 1995 turned out to be anything but for Park, who found in Africa the inspiration he needed to follow his dream—quitting his job in public relations and becoming a full-time writer. Tony and his wife, Nicola, split their time between Sydney and a game reserve in South Africa. It’s been a battle to pull that off in the last year because of COVID-19, but they hope to be back soon.

Park’s books look at the often bloody fight to save endangered wildlife and also draw on his 34 years of experience in the Australian Army Reserve, including a tour of duty in Afghanistan. Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald calls him one of that country’s “best and most consistent thriller writers,” and The Times of London has described him as Wilbur Smith’s spiritual heir.

In this interview for The Big Thrill, Park talks more about the elements that came together to become BLOOD TRAIL.

Mia is a great character. Essentially brought up by the local people in the bushveld, her passion is wildlife and tracking. She has made herself the best woman tracker, maybe the best tracker, in the whole area. Yet she lacks self-confidence in her work and her relationships. How did you develop her?

Mia’s not based on a real character, but I do know some female safari guides, and I drew heavily on stories they told me about what they like and dislike about their jobs. I think all of us, at times in our lives, suffer from self-doubt and a lack of confidence. I know that as a writer I feel so lucky and blessed to be doing the one job in life that I always wanted to, but I’m often wracked by self-doubt. I have to tell myself to trust the process (or, more often, those around me tell me that), and I worked some of this into Mia’s story.

One of the most fascinating aspects of BLOOD TRAIL is the detail about tracking and the poaching trade. I know you have a place in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve area. Is much of this based on your own experience there and with the local people?

Absolutely. One of the things I love about the African bush, especially living there, is that the learning never stops. I love going out on a game drive with a new safari guide and learning more about the environment—not just rhinos, lions, and elephants, but how trackers learn and employ their skills. A good tracker reads the signs and tracks he or she is following, rather than just looking at them. My wife, Nicola, and I are also part owners of a safari lodge in Zimbabwe, Nantwich Lodge, and I love spending time with the guides there, watching them work and learning from them.

On the poaching side, a war is being fought to protect endangered species, especially rhinos, and as I’ve explored in other books, the tactics on both sides keep evolving. It’s hard to keep up with, but it’s a fascinating and important struggle to study.

A key premise of the book is that rhino poachers are eluding expert trackers in a private game reserve in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve bordering the Kruger National Park. Their tracks suddenly disappear at spots usually marked with special symbols from sangomas. This affects the Black trackers dramatically, and even Mia starts to fear something supernatural. Indeed, even the reader starts to believe that something paranormal must be happening. Was exploring these belief systems a major motivation for the story?

Definitely. I was fascinated when a friend, an academic, explained to me that not only do poachers consult their local traditional healers for potions and spells to make them bulletproof, to disappear, but also the national parks’ anti-poaching rangers have the same beliefs and will also carry their own magic. As a Westerner, it’s tempting to dismiss this as superstition, but as an ex-military person, I know that the following of rituals, use of good luck charms, and religion, become incredibly important to people in war, which is what’s known as a high-risk (you might die) and high-reward (you win or you lose) situation. People involved in poaching or counter-poaching are in a high-risk, high-reward situation as well, and their beliefs become a matter of life and death for some.

There’s a lot of in-depth background information about sangomas and their work embedded in the story. How did you research that?

Two academics studying the use of traditional medicines and beliefs in this field gave freely of their time, answered dozens of questions from me, and checked the manuscript. I also conducted a number of interviews with an African friend of mine in South Africa who spoke openly about his dealings with a traditional healer and the medicines and talismans he’d used. When he was younger, he was working as an armed security guard in Johannesburg. Sadly, in parts of that city, there is very real risk to law enforcement and security personnel from armed criminals. He freely admitted that he needed all the protection he could get in his job. To round things out, I was incredibly lucky to learn that one of my editors at my publisher, Pan Macmillan South Africa, was also a practicing sangoma! Her feedback on the manuscript was invaluable.

Sannie van Rensburg is another strong female character. She’s appeared as a protagonist in your books before. In BLOOD TRAIL, she’s working through being a single mother after the devastating loss of her husband, but she remains totally committed to her job as head of the Stock Theft and Endangered Species unit in the South African police. Now she’s faced with kidnappings, murders, and the smuggling of animals—and possibly girls—for muti. Would you tell us a bit more about her?

Sannie came into “my world” in the sixth of my 19 novels, Silent Predator, first as a South African Police Service protection officer, or bodyguard, where she met her new husband. I love her. She’s tough and resourceful and probably bears an uncanny resemblance to Charlize Theron, so what’s not to like?

Seriously, though, her journey has mirrored the ups and down of her country, South Africa, in the post-apartheid era. As a White woman, she had come from a period of privilege and wealth to having to fight for her job, do time back on the streets investigating robberies (in another book, The Hunter), and her family’s farm, her inheritance, was repossessed by the government and redistributed to indigenous farmers. She’s had to face the fallout of violent crime and now lost a partner, all while raising three kids who face a future far less predictable than that previously offered to people of her generation.

Sannie has had to work for everything she’s got. She’s fiercely protective of her children, and while she’s taken some blows herself, her innate sense of fairness and justice always shows through.

An interesting part of Sannie’s journey (from my point of view) is her exploration of the way some African cultures use traditional healing and medicine to deal with grief and what other cultures would refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder. I think there are some lessons in those scenes worth examining.

One of the girls kidnapped is the daughter of a wealthy tourist staying at the upmarket lodge; two others are from the nearby poor rural village. The story juxtaposes these two settings. Mia has a foot in each one. Was this a way to illustrate the diverse strata of society in South Africa?

Yes. Some time ago, before I started writing BLOOD TRAIL, I learned of a terrible trend in parts of rural South Africa and worked this into my fiction. People in a village not far from where I lived were protesting because they perceived that the local police were not investigating the disappearance of a couple of local kids—allegedly because they were poor, or orphans, or “not important.” Action was taken, but it shouldn’t have come to that. It’s impossible to ignore the gap between rich and poor in South Africa, and that stratification is not necessarily on racial lines.

Having said that, I see so much, every day, to inspire me in South Africa. The book is set during the COVID-19 lockdowns and, as happens in the novel, I was inspired to see so many comparatively well-off people there and in other places around the world banding together to provide food parcels, clothing, and other aid for poorer people during the pandemic.

One of the attractions of your books is that there’s so much variety in settings and characters. What are you dreaming up for your next one?

I’ve had to write my 20th novel from the spare bedroom of our apartment in suburban Sydney, Australia, so it’s been difficult! I’ve decided to work a bit of Cape Town and a bit more of an urban environment into the new book as it’s relatively easier to describe from afar. However, I’ve also drawn on my love of Zimbabwe (and our lodge, which I am missing like crazy), to fulfill my daydreams and travel virtually back to the African bush. The book is about arms smuggling and a different type of smuggling—the wholesale pillaging of abalone, a shellfish delicacy prized in some parts of the world.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024