Up Close: Joshilyn Jackson

Revenge, Redemption, and a Mother’s Worst Nightmare

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

“I woke up to see a witch peering in my bedroom window.”

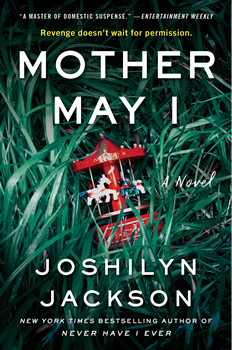

This is the opening line in bestselling author Joshilyn Jackson’s newest thriller, MOTHER MAY I, which explores revenge and how far a mother will go to protect her children.

Jackson says it was “low-down dirty dark fun” to write a revenge fantasy based on a “woman done wrong.”

Upper middle class mom Bree Cabbat has a wonderful life, with three kids, a great husband, financial security, and a beautiful home in the Atlanta suburbs. But everything unravels when someone kidnaps her baby boy from right under her nose.

She’d seen “the witch” twice again that day and suspects she’s the kidnapper. But why would an old woman want to steal her baby?

When the kidnapper calls, Bree expects her to ask for ransom. But instead, she demands that Bree perform a task—attend a cocktail party at her husband’s law firm and administer a drug to her husband’s best friend. And the woman warns her not to call the police.

Bree can barely function, but being an actress, she channels herself into a woman who isn’t falling apart. She follows the kidnapper’s instructions, but when her mission results in a horrific tragedy, Bree knows things are far more complicated than they appeared. The kidnapper has an agenda that has nothing to do with money and everything to do with revenge.

The only thing Bree has working for her is that the kidnapper is herself a mother concerned about her daughter. She hopes the connection between them will get her son back.

But what Bree discovers about the kidnapper’s daughter and her link to Bree’s family will tear her perfect life apart.

Jackson explains why she included the juxtaposition of a traumatic, underprivileged childhood to one of extreme privilege throughout the novel.

“Bree, the main narrator, grew up with a loving but very anxious single mother who clung to the bottom rung of the middle class,” she says. “Bree was never hungry, never homeless, but they were never quite secure, having no emotional or financial safety nets. She got a scholarship, married well, and is now upper middle class, although her in-laws are quite wealthy. Bree chooses not to be an anxious pessimist like her mother, but her current life creates the luxury to make that decision.

“The kidnapper comes from a very similar background, but she never got the lucky breaks that Bree had. Still, they understand each other. Their families are almost mirror images, and there is a dark unfairness in how life has treated them. The kidnapper is a terrible, frightening, dangerous person, but the reader, like Bree, also comes to feel for her.”

As a self-professed “redemption-obsessed novelist,” Jackson gives imperfection, guilt, revenge, and redemption center stage in the story. She “wants readers to think about economic privilege, race, and gender, and how the world treats people differently in a million deeply ingrained ways that are crafty and invisible if they are not affecting you, and debilitating if they are.”

Jackson recounts how her own life correlates to her novel’s protagonist.

“Bree didn’t have an infinite number of chances, but she was lucky, and she got several good breaks and opportunities, just like I did. I should be dead. I was very wild and unhappy as a young woman, but I was born into a fierce, loving, connected family. I made good friends, and educational systems valued me. So I ran for the edge of the world but was dragged back time and time again. I am so grateful.

“Now I’m a White, married, secure, middle-class, American mother. My incarcerated students almost always come from poverty and disordered and/or dangerous home situations. They’re often people who got only one chance, maybe two—sometimes none. If they were not perfect in their limited window of opportunity—did not excel immediately—they got no helping hands and no do-overs. We are such an affluent country, but we believe religious and secular versions of Prosperity Gospel—the good are rewarded with wealth and success, but if you’re poor or failing, you deserve it. We throw away the poor, we throw away people who come out of broken, dangerous families, we throw away what seems unpretty or inconvenient. We throw away valuable, lovely, and sacred human lives.”

Motherhood intrigues Jackson, especially how far a mother will go to protect her family.

“I write about motherhood because it was the single most transformative experience of my life. Having a child is always (or should always be) a transformative experience, but perhaps less so for high EQ [emotional intelligence] people who are already warm and empathetic and loving. But for me, motherhood was like being hit by a truck. I am on the autism spectrum, and I was attracted to writing, reading, and theater to learn empathy, how to recognize when I was experiencing feelings and to name them, and how to connect with other people.

“In grad school I’d get feedback on my stories like, ‘Oh this is funny and interesting, but heartless.’ ‘This is good, but sharp and cold.’

“Having my children changed my capacity for empathy more than the acting, writing, and reading. My love for them is so fierce and biological and sacrificial and greater-than-self. Motherhood let me tap into the deep well of primal love I already owned, but had never truly accessed.

“Bree is a naturally empathetic person. She loves her children as much as I love mine, but it surprises her less. Much of the novel’s depth comes from the fact that the kidnapper is also a mother. They understand each other.”

Jackson believes that art and education matter. Voices matter. She explains her work with the Reforming Arts program, teaching creative writing, composition, and literature inside Georgia’s maximum-security facility for women.

“Reforming Arts works in partnership with Georgia State University to bring higher education into the prison system, and to make space for students to express themselves and access their own narratives. The pandemic has been so challenging. Our students are a hugely at-risk population, and we could not get inside to teach. We’ve spent the last year focusing on and expanding our re-entry programs, which work to help returning citizens find educational opportunities and support, and process trauma.”

Jackson gives The Big Thrill a sneak peek at her next novel.

Jackson learns lines outside summer repertory theater in 1988. Jackson, a former actor, is an accomplished audiobook narrator whose voice work has earned her three Earphone Awards from AudioFile Magazine and three Listen Up Awards from Publishers Weekly.

“It’s a white-knuckle domestic thriller in which a former sitcom star moves home to Georgia to flee an obsessive fan, only to discover her stalker has followed her across the country. Or has he? The threat to her and her daughter is more serious than she ever dreamed, and home is not the safe place she imagined… But of course, it’s not that simple. It never is.”

What advice does Jackson give other writers?

“Writers write. I can’t tell you how many people considered my aspirations cute or silly and undermined me in a million ways. So value yourself. Make the time, honor your own work, and value the people who value your writing! My husband took our kids for entire weekends so I could sit in pajamas in an empty house and write. I married so well!”

What is there about the author her fans might not already know?

“Like Bree, I was a theater kid, and like Bree, I’m raising one. My first degree is in theater—I acted professionally as a young woman, and I do enough voice acting to qualify for a SAG card. I read all my own audiobooks and have read for other authors, including Lydia Netzer, Patti Callahan Henry, and Gin Phillips.

“In my wicked youth, I played everything from the murderer in The Mousetrap to Sonya in Uncle Vanya. Horton Foote himself watched me perform as Jessie Mae in his famous play, The Trip to Bountiful. After, someone asked what he thought of the production. He politely said, ‘I enjoyed it very much,’ but then he looked me dead in the eye, pointed at me and said, ‘And that is as good a Jessie Mae as I have ever seen.’ Having a career in theater, like one in publishing, is a lot about tolerating rejection. I lived on that moment for years.”

- Katherine Ramsland - April 25, 2024

- Flora Carr - March 29, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: EVERYONE IS WATCHING by Heather Gudenkauf - March 29, 2024