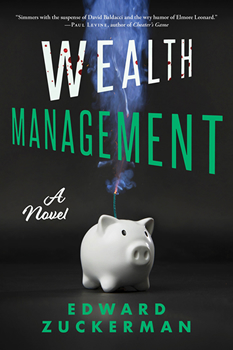

Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman

By Tim O’Mara

By Tim O’Mara

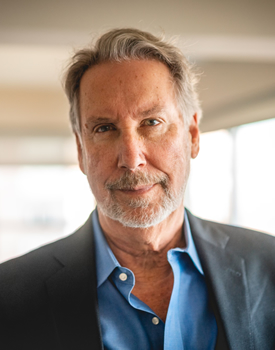

It’s not often a reader looks at the cover of a novel by a first-time author and says, “That guy’s name sounds familiar.” It’s also not often the “first-time author” has written and produced hundreds of hours of JAG, Blue Bloods, Law & Order, and Law & Order: SVU (“That’s where I’ve seen that name!”) and has an Emmy and two Edgar awards on his mantel. (We’re assuming he has a mantel.)

Ed Zuckerman’s debut novel, WEALTH MANAGEMENT, takes us to Geneva and into the high-risk world of three young wealth managers—friends who also happen to be involved in a love triangle—who are handling investments for some dubious clients. The trio comes to realize—a little too late for comfort—that their clients may be Mafiosi or terrorists. They’re not only accomplices, they’re also under threat and—because it’s a thriller—there’s no easy way out.

After a successful career in journalism, including work with Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, and Harper’s, writing two well-received nonfiction books, and then his prolific career in television, what did Zuckerman find most surprising as a first-time novelist?

“It was hard!” he admits. “After writing narrative nonfiction and devising well over 100 plots for TV cop and law shows, I figured writing a novel would be a reasonably achievable extension of what I’d already done. It wasn’t.

“In a script, if you have two characters talking in a bar, you just slug the scene: ‘INT. BAR – NIGHT. John and Mary are sitting at a table.’ And then you launch into dialogue. In a novel, you have to describe the damn bar. (I generally find description in fiction uninteresting and kept mine to a minimum. But I had to write something.)

“Also, even a short novel, which mine is, has so much more stuff in it than a one-hour TV script (which is roughly 55 pages long, with a lot of white space). Characters, their feelings, their backstories, the main plot, a secondary plot, various subplots, stray minor characters, the weather (well, actually, I don’t do weather) are all woven into a tapestry where all the elements come together (surprisingly but inevitably) for a dramatic thriller climax.

“It took me a lo-o-ong time.”

What about the differences in keeping a fiction narrative moving forward compared to nonfiction?

“In writing nonfiction,” Zuckerman says, “you are bound (or should be) by what actually happened. I was fortunate in my narrative nonfiction book (Small Fortunes: Two Guys in Pursuit of the American Dream) that the two Texas businessmen I was writing about were extraordinarily colorful (orgies in hot tubs, airline travel with red cows, etc.). My plan was to chronicle their rise to success, and to do so, I followed them around for a couple of years. At which point one of them ended up going broke and borrowed money from me (the chronicler of his success) to hire a bankruptcy lawyer. The other one lasted a little while longer. This was bad for them but good for the story.

“In fiction, you have to make everything up, which is (have I already mentioned this?) really hard.”

Zuckerman chose to write about characters working in the world of high-stakes finance. What was his research process like?

“I knew people who knew people who worked on Wall Street,” he says, “and some of them consented to talk to me and tell me how things work there. (Although I took a lot of major liberties—Hey, poetic license!)

“My novel is set in Geneva, where some friends of mine were living. I made several trips there to soak up Geneva lore. One of my characters is a detective from Nigeria,” Zuckerman says. “Not surprisingly, I don’t know any Nigerian detectives, and I didn’t know anyone who did. So I needed to find a way to meet some. This is a whole separate long story, but I eventually tracked down an Oxford sociologist named Olly Owen who’d spent time embedded with Nigerian police, and he connected me with several current and former officers in the Nigeria Police Force. I flew to Lagos to interview them, which is extremely helpful. You cannot beat research as an underpinning for fiction.”

How about managing the three main characters’ points of view?

“When I reached a point where something had just happened to one of the characters, and there was some suspense about what might happen next, it was time to leave them hanging and switch to someone else,” Zuckerman says. “I didn’t end my chapters with Hardy Boys-type cliffhangers, exactly. (‘As Joe stepped off the curb, he looked up to see a giant laundry truck speeding toward him!’) It’s the same idea, but a little more subtle.”

Zuckerman chose to write WEALTH MANAGEMENT using very short chapters. Is this related to his writing for television?

“Uh, yeah,” he says. “I’m not sure I should admit this, but it does flow a lot like a television episode. Short scenes (I mean chapters) where something happens. Then you get out early, leave something hanging, and cut (I mean, transition) to something else.”

With all the risks his characters face, Zuckerman was able to keep the tone and dialogue light throughout the book. How?

“I think a dose of humor is essential in good dramatic writing,” he says, “either for television or in a novel. I don’t mean being jokey, but some wit—in the situations, the characters, the prose itself—keeps things lively and interesting. As a reader, I’m bored if I don’t see it. As a writer, it felt only natural. I am not comparing myself to these guys, but John le Carré and Elmore Leonard, both great writers, are very witty. (Ditto, more recently, Mick Herron.)”

Zuckerman uses many parenthetical asides in the characters’ POVs throughout the novel. (They provide humor and some exposition.) Again, what was behind that choice?

“I’m just a discursive kind of guy. I did manage to restrain myself from using footnotes,” he says.

Finally, if Zuckerman could put together his dream panel for ThrillerFest—participants need not be living to be invited (Why discriminate?)—who would be on the panel, why, and what would the topic be?

“Okay,” he says, “let’s go with Leonard, le Carré, and Herron. Let them try to explain why some hugely bestselling crime writers (whom I will not name) write prose that is dry as dust. What is wrong with people?”

We have no idea—but if you come up with an answer, be sure to let us know.

*****

Edward Zuckerman began his career as a journalist, writing about zombies, killer bees, talking apes, and other subjects for Rolling Stone, Spy, The New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire, and many other magazines. He wrote two well-reviewed nonfiction books, The Day After World War III and Small Fortunes, and then moved into writing for television dramas, including Law & Order (50+ episodes) and Law & Order: SVU. He has won two Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America and an Emmy for his work on Law & Order. He lives in Manhattan and Manhattan Beach, California. WEALTH MANAGEMENT is his first novel.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman - September 30, 2022

- Homeland Insecurity by J.L. Abramo - August 1, 2022

- Unruly Son by Neil S. Plakcy - May 31, 2022