Africa Scene: Andrew Brown

A Tale of Two Protagonists

Andrew Brown is an unusual South African crime writer. An anti-apartheid activist, he was given a three-year jail sentence in 1988 for his activities in support of the African National Congress. He argued the sentence down to community service, studied law, and became an advocate and occasional acting judge in the same High Court where he’d appeared as a defendant. Not content with that as a contribution to the community, he’s also a police reservist, which led to Street Blues, a book based on his experiences. Street Blues was shortlisted for the Alan Paton Award for nonfiction.

Somewhere between all these commitments, Brown finds the time to travel and write taut political thrillers that lay bare the issues of Africa through gripping characters. In 2005, Coldsleep Lullaby was published and went on to win the Sunday Times Literary Award, South Africa’s premier award for fiction. It was followed in 2009 by Refuge, which was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Literary Prize: Africa.

This year saw the publication of THE HEIST MEN, a thriller about a gang that attacks and robs cash-in-transit vehicles. The tension comes from two directions—on the one hand, we follow Captain Eberard Februarie in his efforts to track down the gang, but on the other, we follow Andile Xaba, the leader of a crew of heist men who sees his activities with the gang as a career. He leads a double life with a suburban girlfriend and township mother. Despite his role in the gang, he grabs our interest and wins our sympathy.

Brown’s last novel was Devil’s Harvest in 2014—it’s been a long wait for a new book. THE HEIST MEN is worth the wait. In this exclusive interview with The Big Thrill, he talks more about it.

THE HEIST MEN really has two protagonists: Captain Eberard Februarie with the special police unit set up to put an end to the spate of cash-in-transit heists, and Andile Xaba, a key member of the heist gang. Their paths are inexorably linked, not only from the perspective of the action. Did you set out to illustrate the two-way relationship between the police detective and the criminal he’s trying to catch, or did it develop with the story and the characters?

The storyline is based loosely on the movie Heat, with Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. Pacino is the tough cop and De Niro the rather likeable heist-gang leader. In my favorite scene, Pacino and De Niro meet in a coffee shop and have a conversation. They talk without acknowledging expressly who they are, although of course they are entirely aware, having tracked one another for the better part of the film. De Niro says, “I do what I do,” and Pacino responds, “Well I gotta do what I do.” They part knowing that they cannot both survive the hunt.

In my book, Eberard and Andile meet in a coffee shop and have a similar conversation, but the theme of their conversation is, in essence, that they need each other. The robber is defined by the cop, the cop’s existence presupposes the robber. That’s a long way of answering yes—from the beginning I wanted to portray both sides. Eberard isn’t a better person than Andile—they have made different choices, to be sure, but both have been motivated, and pressured, by their personal circumstances. I truly enjoyed the challenge of portraying both sides of the story.

Februarie has a complex personal life involving alcohol, an estranged wife, and a daughter he neglects. This seems to be a standard model for senior police officers in the South African Police Service. Are the demands of the job and the issues they have to deal with so crushing that this is almost inevitable?

On the other hand, things seem to be looking up for him in THE HEIST MEN. Did you decide it was time to give him a few breaks?

The demands of the job are crushing in many ways—in my two nonfiction accounts of being a police officer, I tried to give the reader some insight into the slow grinding traumas of police work. The demand of being courageous, strong, resilient, compassionate, sensitive, conscious all at the same time—and then witnessing on a daily basis the trauma that life happily dishes up to ordinary, innocent people—it is honestly a tall ask to expect anyone to maintain a normal, healthy lifestyle at the same time.

I recently pointed out to Deon Meyer that his Bennie Griesel and my Eberard Februarie seem both to be enjoying a rejuvenated personal life, having wallowed in self-pity and trauma for several novels. I asked whether it was coincidental that we had both experienced the anguish of divorce and now had rekindled our faith in relationships. He just laughed.

From my side, I felt it was time to give Eberard some happiness—he really has been through hell! The honest answer, I suppose, is that I wanted to try my hand at writing some romance, so Eberard got a lucky break.

The heist gang calls itself Boko Haram, which is the name of an Islamist terrorist organization in Africa. Is there any significance to the choice of name?

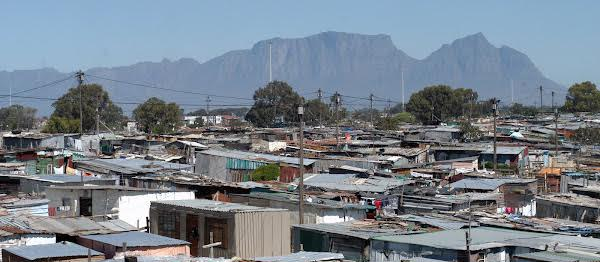

Boko Haram was the actual name of a heist gang from Nyanga. I was so fascinated by the fact that they chose to name themselves after a terror organization. It seemed both cynical and quite brilliant—even the police officers investigating them were nervous about confronting them. I was peripherally involved in tracking this group and got to learn of some of their tactics—which needless to say were substantially more vicious and terrifying than the approach adopted by the heist gang in my book.

Xaba is a fascinating character. He is a key man in Boko Haram, but he has a complicated personal life and is clearly multitalented. Greed is an issue in his career choice, but so are circumstances. Was it important to develop him as a three-dimensional person and not relegate him to the role of the main “bad guy”?

It was absolutely my intention to make Andile a rounded and hopefully resonant character. My hope is that a conscious reader will look at Andile and his choices and realize that, faced with his pressured circumstances, they might end up making similar decisions. He is motivated by a desire to support his mother, his child, perhaps win back the mother of his son, gain status in his community, and prove to himself that he is not destined for ambivalence and failure.

I’m not sure that he is greedy in the conventional sense, but he has ambition for success, though not purely in a financial sense. He justifies his activities on the grounds that it is a victimless crime, that the money belongs to no one. Of course, he knows that this is tenuous and that innocent people may well be hurt or killed.

Part of my interest in the theme is the fact that we all watch bank heists or other clever scams (the Ocean’s series of films comes to mind) where we wholly buy in to the idea of a victimless crime (or a victim who deserves it). In Heat, we would quite like De Niro to succeed; in your average Netflix bank heist series, we are rooting for the criminals. I would hope that at least some part of us wants Andile to bring it home.

You joined the South African Police Service Reserve in 1999, and you are now a sergeant. Clearly you have experienced a lot firsthand, and you must have great contacts in the SAPS. How much of THE HEIST MEN is based on real-life experiences?

I think all writers draw heavily on what they know, what they have felt, their own particular experiences. Certainly, many of the scenes in THE HEIST MEN are based on situations that I have experienced. I have worked in the gang unit, I ran the satellite station in Masiphumelele, I have tracked suspects all over the Cape Flats, so all of this helps. But ironically, much of the interaction with Eberard and Maria, his new relationship interest, comes out of my work in the Child Abuse team at Red Cross Children’s Hospital, which is where I am now based. The teenage pregnancy of his daughter, his involvement in a statutory rape case, his getting to know the social worker Maria—these are all drawn from my work in the Child Abuse team.

An important facet is the tensions between the “new” SAPS officers and those who were in the police before the change of government. It seems to generate suspicion and divided loyalties. This works well in the story. Is it still an important factor in the SAPS and will it continue until all those officers have retired?

I think that it is slowly resolving as time passes, but it is still always in my mind when I meet an older officer. The suspicion of “where were you in 1988” still plays in my thoughts. But for me personally, it has been part of my healing. I was traumatized as a young man at the hands of the South African Police and its security services. Working with some of those officers has allowed me to come to terms with some of my post-traumatic stress. I worked in the Nyanga Homicide detectives alongside a superb policeman who had been in the Riot Squad as a young constable in the ’80s. It turned out I had thrown rocks at him and he had shot me in the leg with a teargas canister. We laughed, shook hands, and got on with the murder at hand. Of course, there are those who I can never forgive. There are some who I believe have no place in the new police service.

It’s been quite a gap since your previous Eberard Februarie novel. Can we hope to hear more about him in the near future, or do you have a different fiction project in mind?

In fact, I have another manuscript with my publisher, which already has been given a green light. It’s an adventurous book stylistically, set mainly in Gaza but involving different historical threads and stories that all come together. I think it could be quite special, if it works, but the completed manuscript needs work. So that is my task for the next year at least. After that, we will see.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024