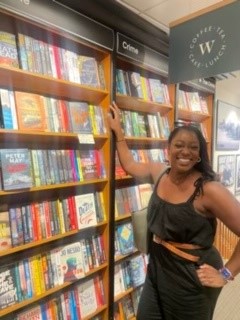

Up Close: Nadine Matheson

Exorcising the Ties That Bind

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

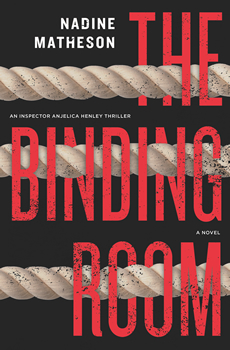

In her second #ownvoices thriller, THE BINDING ROOM, London criminal-defense attorney and award-winning author Nadine Matheson once again spotlights law enforcement’s misogyny and racial stereotyping—and this time mental illness is at the heart of the story.

Detective Inspector Angelica Henley knows what it’s like to be treated differently because she’s a Black woman in a white man’s job. She can’t count the number of times other law enforcement officers have asked her to prove her identity. Still trying to deal with the emotional fallout from twice being attacked by the serial killer Peter Olivier, she must also keep her emotions from getting in the way of their latest investigation in the Serial Crime Unit.

Henley and her coworker, Detective Constable Salim Ramouter, are called to the scene of a murdered pastor. Dr. Caleb Annan runs the first mega-church in Deptford, the Church of Annan the Prophet. And yes, Annan considered himself a prophet. But it’s obvious he didn’t predict that someone would stab him 48 times and leave him bleeding out on his sanctuary floor. Then, when Henley investigates the upper floor of the church, she discovers a hidden room and a tortured victim that shocks the hell out of her.

As Henley and Ramouter investigate, they find more tortured victims, all connected by suffering from mental illness.

Besides working the gruesome case, Henley must juggle her relationship with her boss—her old friend and lover, and also a victim of Peter Olivier—and with her husband. Ramouter must also come to terms with his injury from the Olivier case and the guilt he feels at not being able to care for his wife (who has early onset dementia) and their son like he needs to.

Then there is the accusation lobbed against Henley that she’s betraying every Black person whom she’s investigated or jailed. Just by doing her job, is she abandoning her responsibility to people of color? As the case continues, feelings of guilt and anger intertwine with the investigation.

Matheson again uses her narrative as a platform to address the need for justice: Issues of racial bias, misogyny, and the stigma of mental illness are skillfully written into the storyline, giving readers a real-world view of what it means to be treated as less than.

Below, Matheson talks with The Big Thrill about how a real-life defendant inspired the novel, how her job as a criminal defense attorney informs her books, and the importance of addressing social issues in her stories.

What was your inspiration for THE BINDING ROOM?

A few years ago, I was at Isleworth Crown Court in London for a trial, and in the courtroom next to mine, a defendant was on trial for “Causing Grievous Bodily Harm with intent,” which is one of the most serious assault charges in English law. I’m not sure what it was about the defendant—what he wore or the way he carried himself—but I remember thinking that the defendant wasn’t your usual criminal. I then discovered that the defendant was on trial because he’d attempted to perform an exorcism on a family member.

The strange thing about criminal cases is that sometimes they’re cyclical, and that year there was a torrent of trials where the defendants were charged with assault, manslaughter, and murder because they were conducting exorcisms. Everyone involved in those trials held the firm belief that they were trying to free their brother, sister, wife, or friend from demonic possession and adamant that they’d done nothing wrong. Those cases and the people involved, who looked as normal as your grandmother’s friends, always stuck in my mind because they were carrying out such violent acts, some going so far as to take the lives of family and friends with little or no remorse.

I also grew up in the church—my late grandmother was a reverend, and I went to Catholic school—and I always felt that churches were their own world, with separate rules and regulations that would appear abnormal in the non-secular world. It was these things that inspired me to write THE BINDING ROOM.

How has your experience as a criminal solicitor informed your novels?

I’ve been working in criminal law for almost 20 years, and I’ve always felt that my profession provided me with the best environment to observe human behavior. You can have the best plot in the world, but you have to convince your readers of the authenticity of the characters for them to be invested. We all have a clichéd image of how a burglar, thief, or murderer might look, but I realized early on that the defendants I represented were unique and multifaceted individuals.

Authenticity is very important to me—I can invoke my personal experience when describing the claustrophobic feel of a police interview room or the smell of a court cell. In my opinion, “storytelling” is part of being a criminal solicitor. I’m basically telling a story when I’m giving a closing speech to a jury or drafting a legal argument. I want the jury to believe that what I’m telling them is true and to be invested in my defendant’s story. Those basic principles apply when I’m writing my novels.

Can you expand on the themes in your novel that revolve around equity and change? Not just for victims, but for law enforcement professionals of color.

I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that there could be 20 people charged with the same offence, but their own individual circumstances and standing within the world—whether that’s socio-economic, ethnicity, or both—will affect both their perception of their predicament and how they choose to navigate their way through a case. This not only applies to defendants but also to the victims and law enforcement professionals of color.

The lack of equity means that both victims and law enforcement professionals of color must always overcome the hurdles of clichés and racial stereotypes. This includes proving that their race and gender aren’t barriers in their ability to do the job or to receive equitable treatment when their case is investigated.

In my novels, it’s important to show how Detective Inspector Henley, as a Black woman and Detective Constable Ramouter, as an Asian man, constantly have to reinforce to victims, colleagues, and even their family members that their color isn’t a hindrance in their ability to do their jobs. That we’re not in a space of equity means there’s always an element of mistrust in the relationships that victims and law enforcement professionals of color must overcome.

Can you give us more insight into how the justice system is biased against marginalized groups and people of color, specifically against those in law enforcement (especially as a Black woman)?

To be blunt, there isn’t a level playing field, and it would be unrealistic to not show how the constant battle of dealing with people’s prejudices, preconceptions, and stereotypes has both an emotional and mental impact on marginalized groups. People of color are overrepresented both in the court and the prison system, and they’re continuously stigmatized. In the UK, a Black person is four times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police compared to a white person.

From my own experience, the justice system is biased because the starting point is always one of racial stereotypes and clichés, and this breeds mistrust. I’ve lost count of the number of times someone assumed that I was the defendant’s girlfriend, family member, probation officer, or anyone else other than the defendant’s lawyer. Can you imagine how exhausting it is to repeatedly defend your position and the authority you hold?

There is an unconscious bias on both sides of the justice system that your race, gender, or inclusion in a marginalized group is a precursor to your guilt or your role in law enforcement. Those from marginalized groups and people of color who choose to enter law enforcement always have to be prepared for community members and their own colleagues to challenge them about the position they hold. I don’t think the drive by institutions to make the justice system both more diverse and fairer will work if they don’t address the unconscious bias that people hold.

Is there a message you’d like readers to take away from the novel?

Mental health and the dismissal of mental illness are strong themes of the novel. There are countless occasions of people saying “Oh, I thought something was wrong, but I didn’t say anything.” You’re not invading someone’s privacy if you enquire about their well-being and don’t accept “I’m okay” as a final answer.

Sometimes, there is a misconception that asking for help or even acknowledging that mental illness exists is a sign of weakness. Check on your neighbors, check on your family and friends. My message for readers is to never fear asking for help or asking if someone needs help.

Can you give us a hint about your next book?

Henley and the Serial Crime Unit will reopen a 25-year-old murder investigation when new evidence suggests that the man convicted of the murders is innocent, and that the actual killer may be out of hibernation.

What advice can you give other writers?

There are no overnight successes, so don’t get distracted by who’s on top of the bestseller list or who’s just got a seven-figure deal. Don’t worry that you’ve submitted a novel to an agent and that it’s been rejected—again. There is not one writer who doesn’t have a rejected novel (or two) sitting in a drawer; it’s all part of the writer’s journey. Persevere and write the story you want to tell. And never stop reading.

Tell us something about yourself your fans might not already know.

One year, I made a New Year’s resolution that I would appear in a film. After joining a casting agency, I was an extra when they filmed an episode of 24 in London and in an Idris Elba movie called The Take. I quickly decided that waiting around in the cold for hours on a film set was not the life for me.

- Katherine Ramsland - April 25, 2024

- Flora Carr - March 29, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: EVERYONE IS WATCHING by Heather Gudenkauf - March 29, 2024