BookTrib Spotlight: Bryan Christy

A Wildlife Journalist Discovers the Most Dangerous Animal is Man

In Bryan Christy’s IN THE COMPANY OF KILLERS, Tom Klay has a unique and specific job—he’s an investigative wildlife reporter for a world-renowned nature magazine:

“Nature had become his murder book. From A to Z—from the spiral-horned addax to Grevy’s zebra—he exposed crimes against endangered species in the pages of The Sovereign, and then, like a television detective with a season to fill, moved dutifully on to the next victim. One didn’t linger over the dead, in fiction or in life. One moved on.

“He was selective in the stories he took on. Winnable cases only. He was no Don Quixote. He didn’t investigate crashing insect populations or stranded polar bears. He didn’t report on the global warming crisis for the same reason he didn’t investigate Russian money laundering, Mexican drug trafficking, or Wall Street’s financial crimes. Those stories weren’t winnable. He identified traffickers, designed investigations, reported his stories, and hoped the system did the rest.”

However, all that is about to change. In Kenya to report on elephant-poaching, a good friend is murdered, and he himself barely survives. It is the work, he is sure, of a South African criminal named Ras Botha, and given the chance by the magazine to work with a South African prosecutor—who is also an old flame—to bring him down, he seizes the opportunity.

Something feels off, though. His magazine has been bought by the media arm of an international security company. The CIA contact with whom he’d been working on the side has suddenly been replaced. His former lover is skittish, obsessed with secrecy. More people are turning up dead. Has Klay been sent to seek justice—or is he a pawn in a game so complicated he can’t even see the board?

In an intricate and exciting thriller that is full of surprises, Tom Klay will discover that everything he thought about this case—and the events of his own life—have not been what they seemed. The lines between good and evil have just been blurred, and in the end, it may be only his enemies that he’ll be able to trust. A little.

Bryan Christy knows what he’s talking about. He’s the former head of Special Investigations for National Geographic, a documentarian whose film “Warlords of Ivory” was nominated for an Emmy, and the author of a book about reptile-smuggling, The Lizard King, described by The New York Times as “a wild, woolly, furry, feathery, and scaly account of animal smuggling on a grand scale.”

How much of Christy was in the character of Tom Klay? It’s quite a story:

“That’s the beauty of fiction, what surfaces from your subconscious as you write—is it your invention, or is it you? Tom Klay is a fictional character. The story is made up. I drew on my experience as an investigative journalist to give him an authentic life, but Klay’s a different guy. He’s darker, more cynical. He’s had some terrible experiences I haven’t had. That said, we do have certain things in common. We both grew up in a funeral home, we both worked as criminal investigators for a famous international magazine. Klay employs investigative techniques I’ve used. In the end, though, Klay accepts the CIA’s offer, which is something I would never have done as a journalist.

Christy takes a break while on assignment for National Geographic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Christy is the founder and former head of the magazine’s Special Investigations Unit and a recipient of the prestigious Rolex National Geographic Explorer of the Year award. Photo credit: JJ Kelley.

“Until I came along, every male Christy since 1898 had been a mortician. If I was going to break family tradition, I felt I had to be responsible about it. I did what writers do when they can’t bear to disappoint their parents. I went to law school. I was working at a firm in Washington, DC when I got word my father had only a few days to live. Before he died, I decided I had to tell him why I’d become a lawyer. We were in the hospital. He was unable to swallow. I was moistening his lips with an ice cube. He looked at the bowl I was holding and said he would give everything he owned for a whole ice cube. Everything. He told me never forget that in the end that’s what it would come down to. He loved to fish, he said. If he had it to do over, he would have spent more time in his boat out on the lake, fishing.

“I enjoyed law, but it wasn’t my boat on a lake. I went back to my firm and quit. I was going to be a novelist. I waited tables for a while. After two years without a book, I sold my Capitol Hill house and moved back to the family funeral home. I lived upstairs and wrote. After a couple more years, an uncle who was an FBI undercover agent reached out to me and offered to tell me his story. That led to his training me to be a criminal investigator, which threw open my imagination. One of my childhood passions had been reptiles. I decided to investigate that industry.

“While I was working on The Lizard King, I met an editor at National Geographic who asked me how I would approach a story assignment from them. I looked at Nat Geo’s work on animals and realized their typical wildlife articles were crime stories that lacked both a villain and a crime story’s dramatic arc. I proposed modifying their approach to move from victim-based stories featuring endangered species to villain-based stories that exposed kingpins and corrupt government officials. As a trial, they hired me to go after a trafficker operating in Malaysia. The result was effective in terms of reader engagement and impact. Over the years some bad people went to prison and, some endangered species got better protection.

Christy with wild elephants at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s (SWT) Ithumba Reintegration Site in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya. The SWT operates the world’s oldest and most successful elephant orphan rescue and rehabilitation program. Photo credit: John Heminway.

“I loved all of it. Truly. The first time seeing an elephant in the wild. Or a giraffe running free. Getting arrested in Tanzania, of course. We were moving fake elephant tusks through the airport in Dar es Salaam for a story on ivory trafficking. The tusks had satellite-based GPS systems and lithium batteries embedded in them. But on the night before I was to put them into the black market, I realized we’d neglected to protect the batteries. People cut into ivory. Lithium batteries explode if you cut them. The tusks were weighted inside with ball bearings. What I was carrying was a bomb. I called off the operation and was bringing the tusks home when we were stopped. The x-ray machine identified the tusks. It was a long night, but I made a lot of friends among those who arrested me. Later we redesigned the tusks and launched them successfully.

“One of the most important things I learned in my years as an investigator is the power of humor and that decency exists at the bottom of most people. The challenge is to communicate yours and listen for theirs. In my fiction I want to continue to give life to that.”

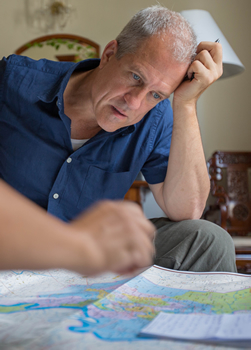

Christy plans strategy to meet and expose an ivory trafficker in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Photo credit: John Heminway.

He also credits his influences: “My uncle the FBI undercover agent taught me how to investigate. My father the mortician taught me empathy. I spent a number of years with a Philadelphia jeweler and fence who showed me the difference between right and good; wrong and evil. After quitting law, I had the extraordinary fortune to spend a summer with James Alan McPherson at the Iowa Writers Workshop. He showed me the importance of writers to society and helped me believe in myself as a writer.

“Ralph Ellison’s celebration of natural language got me off the ground as a writer early on. For this book I read Miller’s plays and Tarantino screenplays to keep a rhythm going. Samurai stories like Lone Wolf and Cub and Kurosawa films like Seven Samurai and Yojimbo for mood.”

And there’s more. The book is filled with intricate detail about a host of things—hunting, Africa, international geopolitics, weapons systems, computer security, and a good deal more. Some of it came from his own work, of course, but other areas required research:

“I approached the book the way I would any investigation. I drew a tree of my main issues and characters and set about learning everything I could about them. More than once I imagined the most outrageous form of corruption I could, only to see it happen in real life. In most cases I scrapped those scenes. A few times, I made them bigger.

“I was surprised to learn that the CIA actually does maintain a non-profit venture capital firm to seed high tech startups. It’s called In-Q-Tel, the Q purportedly coming from James Bond’s fictional inventor. The mixing of fact and fantasy by real world spies engaged in Wall Street investing struck me as too good to pass up as a novelist.

Christy prepares for antipoaching patrol in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Garamba National Park. Photo credit: JJ Kelley.

“I was also interested to discover that National Geographic has early history with the CIA, including one disastrous effort to plant a listening device on the Chinese border, resulting in plutonium rolling down a Himalayan mountain into the Ganges. Charles McCarry was CIA before he became editor-at-large for the magazine; he later turned to writing successful spy novels, as you know.”

I was particularly curious about one anecdote in the book concerning the magazine, a bull’s balls, and a particular variety of grapefruit. It sounded way too specific to be anything but a true story—but, asked about it, Christy sidestepped gracefully: “Hah. I’m glad you liked that vignette. I’m going to evade your question so that it doesn’t inspire further parsing, but it is certainly true that a lot goes on in a magazine’s kitchen, and I try very hard in the book to convey the feel of magazine life as I experienced it. I note that the word grapefruit does not appear anywhere in my published work. Of course, in the end, it also doesn’t appear in Klay’s.”

The Lizard King was nonfiction, but as anyone knows who’s tried both, fiction is an entirely different animal. What was the transition like for him?

“You’re right. Non-fiction has handrails, especially true crime. Chronological sequence is always there to assist you. So are facts. You have them or you don’t. You hit limits on what you can accurately say about a character’s internal life. At some point you have to move on.

“Fiction has no limits. Genre helps. A crime helps. But you have many, many more choices to make, and discarded choices don’t always stay dead. A geopolitical thriller should feel real, the danger impending. One of the main reasons I left National Geographic to write fiction was to explore topics that are too large to fit into a magazine article. If I’m right about what’s coming, readers should definitely be concerned.

“I loved writing the book. I wanted to write the kind of book I like to read—a good adventure story involving real world forces and full characters that makes me feel a little smarter for having spent the time. I’ve crossed paths over the years with a fair number of private military contractors and long wanted to write a story about that world. I’d recently done a project in South Africa where I met some criminals who were both ruthless and charming, and then just when I needed extra inspiration in the villain category, Rupert Murdoch bought National Geographic. Imagination took over from there.”

It was still a long slog to publication. His enthusiasm for fiction didn’t necessarily mean that other people were interested in his fiction. But as with everything else about Christy, there’s a story.

“Years ago I wrote a novel and sent the manuscript out to dozens of prospective agents. I received so many rejections back I thought if everyone deluges them the way I had, they can’t possibly be keeping track, so I picked out the most famous New York agent on my list of rejections and wrote back, ‘I’m glad you enjoyed my manuscript. Yes, I’d be delighted to discuss it further…’ It worked. I got a meeting. Sadly, our meeting was set for September 11, 2001. Instead of discussing my book that day, I found myself as a volunteer near ground zero when the towers came down.

“Like many people I wanted to do something in the wake of 9/11. I abandoned that novel and decided to explore two paths, promising myself that whichever opened up first I would follow it. I reached out to a contact at the CIA, and I set to work writing my first article as a freelance journalist. Journalism won out. Twenty years later, I’m back to fiction, getting to explore all three worlds on the page.

“Jennifer Joel at ICM has been my agent since The Lizard King. I was thrilled Putnam responded so positively to the early draft of this novel and have very much enjoyed working with my editor Mark Tavani.”

And now? “By the end of In the Company of Killers, Tom Klay has finally found peace. It turns out that doesn’t last.”

Can’t wait. For readers, Tom Klay is definitely a winnable case.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- MARS, THE BAND MAN, AND SARA SUE with L. Marie Wood - May 3, 2024

- HITCHHIKER with Vincent Zandri - May 3, 2024

- JIM AND KATHERINE with Traci Hunter Abramson - May 3, 2024