Up Close: Hank Phillippi Ryan

Embracing the Panic

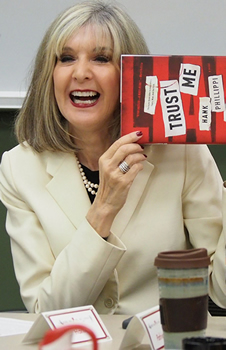

After 43 years as an investigative reporter, Hank Phillippi Ryan thinks, speaks, and dreams in the language of story. Though she didn’t get around to writing a novel until she was 55 years old, Ryan’s entire professional life—which has netted her 36 Emmys and 14 Edward R. Murrow Awards, along with numerous Agathas, Anthonys, and Macavitys—has been steeped in storytelling.

“After all these years as a reporter, I know how a story has to be,” says Ryan, who began her career as a journalist in 1971 with Indianapolis’s WIBC Radio. “It has to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has to have a character you care about and an important problem that needs to be solved. You need the good guys to win and the bad guys to get what’s coming to them, and in the end, you want some justice and you want to change the world a little bit. My thrillers have to have all those exact same elements that my television investigative stories do. So when I’m looking for a story, I’ve learned that I have this bizarre faith in the process—that at some point the universe will present an idea to me that will feel instantly like the idea that could launch a novel.”

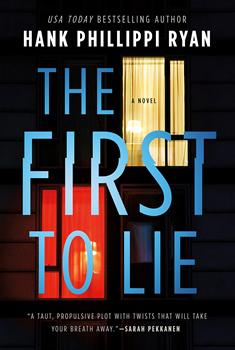

In the case of Ryan’s latest thriller, THE FIRST TO LIE, that idea took her to a very different place than where she started. The novel began as a meditation on the danger—or, perhaps, the dangerous allure—of going undercover: what if a reporter became so enamored with an assumed identity that she preferred it to her real one?

“That’s where the book started,” Ryan says. “Two people in one identity—how do we be someone else? And then I started thinking about how all of us, whether we’re in disguise or not, behave differently depending on where we are and who we’re talking to. All of us are sort of in disguise at one time or another. Who is the real you? is a big thematic question.”

The story that would become THE FIRST TO LIE eventually strayed far from that first what-if, but the kernel of it is still there. As the title hints, there’s more than one liar in Ryan’s latest cast of characters. We learn on page one that at least one character is playing at being someone else. “Nora for now” works for Pharminex, a big pharma company that stands to make billions on a drug that could offer hope for some women struggling with infertility—and, though they leave this part out of the brochures, devastating consequences for others. Meanwhile, investigative reporter Ellie Berensen is chasing a story about the same company for Boston startup Channel 11. As Nora and Ellie get closer to uncovering the company’s secrets, the powerful family that controls Pharminex proves it has no qualms about taking extreme measures to keep those secrets hidden. The Vanderwalds already have one suspicious death in their history, and they might be willing to add more.

What follows is a masterfully constructed puzzle box of deception, misdirection, and writerly sleight-of-hand that once again places Ryan firmly in the top tier of thriller writers. In this exclusive interview with The Big Thrill, she talks about the realization that launched her publishing career, the cat-and-mouse game she plays with her readers, and how she overcomes the insecurities that set in as she begins each new novel.

Do you have a certain type of reader in mind when you write?

I think my readers are smart and savvy and intelligent, and they’re also diabolically good. They try to figure out my stories before they get to that point in the book, and they crow when they do. And so my job, with my author’s sleight-of-hand and misdirection, is to prevent you from figuring out what I’m about to do. My books are cat-and-mouse thrillers, and that’s sort of how I look at my relationship with my darling readers: this is a cat-and-mouse game, and let’s see who’s going to win. I love it. I was just with a big book group last night on Zoom who had been wonderful early readers for THE FIRST TO LIE. They took me through their thought processes in how they read the book. And after a couple of minutes I said, “Can’t you just read the book and have the joy of surprises on every page?” And they said, “No, we have to figure it out.”

It’s Gone Girl’s legacy—we all look for the lie.

Totally! Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. And now I’m very cranky and annoyed about all the books that come out where it’s all about the twist: “You won’t believe that twist!” Don’t tell me there’s a twist, because now I’m gonna look for it on every page. I think it detracts from your pure enjoyment of the book. We know when we’re reading a good book, and the walls fall away, and we’re transported to a different world, and we are living in this story. That’s what I think a really good book does: takes you away from your analytical brain and puts you in once-upon-a-time brain. That’s what I’m hoping to do. But, no, I get these intellectuals. [Laughs] I get these intelligent, detective-y readers who are untangling things on their own. Anyway, the book group was inspirational because it does make me understand that my readers are smart and clever, and they’re on the storytelling train with me. It’s really a joy to imagine people turning the pages of my book and forgetting the real world. That’s my goal.

This novel involves an impressive display of literary sleight-of-hand. From a craft perspective, how was the experience of writing it different from your previous books, if at all?

What an interesting question. First of all, thank you. I’ve written nine books in two series, and then three standalones: Trust Me, The Murder List, and THE FIRST TO LIE. The glorious exercise was learning to write a standalone. In a series, the suspense has to come from something other than the main character’s mortality, right? Jane Ryland is not going to die in book five of my Jane Ryland series, because there’s going to be a book six. The reader knows that no matter what the level of peril, Jane will come through that somehow. So the key to writing a series is to make a fabulous, riveting, interesting adventure that is still compelling even though the reader knows that the main character is safe. And that’s a juggle. So in a series you’re always putting someone else at true risk.

But in a standalone, it was this gasping realization to me that anyone could be good, anyone could be bad, anyone could be lying, any seeming good guy could turn out to be a bad guy and the other way around. And anyone could be guilty, and anyone could die. I just remember sitting at my desk thinking, Wow. The reader has no expectations in a [standalone] thriller. The main character could die, the main character could be bad. Who is the main character anyway? The main character could be someone unexpected. You can do whatever you want, and that is the glory of writing standalones.

You talked about the similarities between reporting and writing a crime novel. I’m also curious about the differences. Are there any skills that you had to learn from scratch? Are there any habits that you have to make sure don’t transfer from one to the other?

Two things. One is, when I started writing fiction, I really worried that I would not be able to make things up. I’d been a reporter for 30-some years and I’d spent 30-some years only giving the facts, only describing what I’d seen, only using the dialogue that people actually said, only being allowed to use documents and facts and papers and research and actual evidence to turn into a story. In some ways, being a journalist is easier because the puzzle pieces of the story are already presented to me. I dig them up. And my job is to take these complicated puzzle pieces, select which pieces are the important ones for the story, and then put them together in a compelling way. But in writing fiction, not only do I have every puzzle piece that I could possibly want, I can have any puzzle piece that I could possibly imagine. And so I worried that I would not be able to think of puzzle pieces, because I was so used to using facts as my pieces. I remember writing the first page of my first novel, Prime Time, and looking at that page and thinking to myself, Where did that come from? It almost brings tears to my eyes to tell you about it. I know this sounds so silly now, but there was this moment of real awareness that my imagination could work. And it could make up a realistic, reasonable, but exciting and unique world that didn’t exist before. And that was a profound moment in my life.

Twelve books later, has it gotten easier or harder?

I’m in the midst of my 13th book, and unquestionably, it’s more difficult now than it was before. Early on, when I didn’t understand how difficult it was to be good, I would just sit at my computer and type along and pat myself on the back and tell myself I was a natural and how great this was going to be. And then at some point I became an author, and this became a Job with a capital “J.” And I say this in the most delighted of ways, in the most respectful and joyful of ways. But now I have a responsibility to readers to make these books be fabulous and better and raise my level every time. I’m determined to do that.

I still wonder if I can make stuff up. There are days that I sit at my desk and I think, I don’t know how to do this. How did I ever do this before? I have no idea how to write a book. I don’t even know how I wrote those other books. No matter if I did or not, I can’t do it now. I mean, absolutely just a complete brain-not-working situation. And what I do at those moments is I say, Okay, you can’t do it. Too bad, honey. I feel bad for you. Just write one sentence. If it’s terrible, you can fix it later. So I write one sentence. And I think, Well, that’s terrible. Now write another terrible sentence. And I just keep writing terrible sentences. And at some point, I’ll have an idea. And then I think, Oh, this is what I’m meant to be writing. And somehow those terrible sentences aren’t so bad. And then at some point, with a little tweaking, they’re kind of good. And then I go ahead. You know what I’ve learned to do? I’ve learned to embrace the panic. That’s a good way to put it.

I want to return to something that you said earlier when we talked about writing a series versus standalones. Do you find one more fulfilling as a writer? Or do they each scratch a different sort of creative itch for you?

It is such a different experience to write a standalone [versus] a book in a series. In a series you’re going back to a world you know, with a character who’s on a big arc. A series book has two tracks: the track of the actual plot of that specific book, which will end in that book, and the emotional, personal track of the main character, which will not end in the book. So while I’m writing a series book, always in the back of my mind is the question of how to give it everything I’ve got within a time span. It’s not that I’m holding back, but some parts of the story can’t be told because they haven’t happened yet, if that makes any sense. The glory of a standalone is that everything is on the table all at once. This is as big and good and fabulous as it’s ever going to get. This is the most important thing that has ever happened in these people’s lives, and you’re going to hear about it right now, and that’s pretty exciting. So I feel that I can go bigger in a standalone.

Can you share anything at all about what you’re working on now?

Is there a way for you to type that she burst out laughing? Let me check my little chart: I am at word number 62,659 of the new book. Thirty thousand of those words are fabulous; I just don’t know which ones they are. It’s due in about a month. I am terrified about it, but I know that this is how I feel with every book. So yet again, I am embracing the panic. I look at my Agatha Awards and I look at my Mary Higgins Clark Award and I say to myself, This has worked in the past, and you can do it again.

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022