Author Guided Tour: Jeff Soloway

Getting Close to the Edge

By Jeff Soloway

When it came time to select the setting for my second Travel Writer novel, I presented my editor with several options. He nixed my first choice. “You can’t have a murder in Walt Disney World,” he said. “We’ll get sued.”

The place we settled on was the Grand Canyon.

The Grand Canyon is perfect for a crime novel. It’s beautiful, of course, and like a lot places of great natural beauty, it’s potentially deadly, but more than that, it’s obviously and immediately deadly. In the Grand Canyon, you don’t have to spend all day climbing a mountain to risk a deadly fall. There are plenty of breathtakingly steep drop-offs within a few steps of any viewpoint parking lot. The accessibility of danger is part of the Grand Canyon’s appeal.

You hear lots of nervous laughter at the top of the Grand Canyon. As likely as not, a couple nearby will be giggling about the famous “Grand Canyon Divorce”—no lawyers, no papers, no hassle, just a shove.

Most people, after getting their fill of the vertiginous view, quickly step back from the edge. But some feel the urge to start clambering. At many of the viewpoints, you can skirt the protected areas around the nearest cliffs and instead take little informal trails among the surrounding rocks and crags. The best trails dead-end at stunning little outcrops that jut out into nothingness. You’re free to gaze down over the edge and have your own private near-death experience.

Of course, you’re not really going to die in the Grand Canyon. You watch your steps. You stay a few feet from the edge. You hold your children’s hands. You could just as easily slip and fall off the sidewalk in New York City and kill yourself in traffic. Millions come to the Grand Canyon every year and manage to survive.

But not all. About a dozen visitors die each year, according to the National Park Service.

My last trip to the Grand Canyon had a specific purpose—I wanted to find the very best place in the Canyon to set my novel’s murder. I decided to take the family along, because there’s nothing like bonding over imaginary murder.

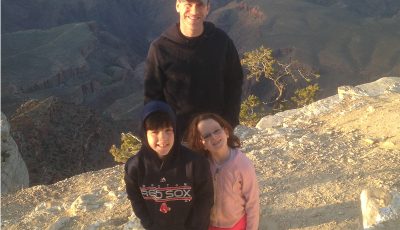

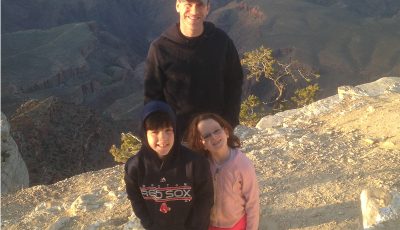

We began, at everyone does, by exploring those rimside, parking-accessible viewpoints. They were as stunning as I remembered, but also as crowded, even on a chilly April evening.

As sunset fell, we strolled—carefully—down some winding trails for better views.

My son and I scrambled further out.

But our strolls and scrambles still left us in full view of hordes of viewpoint visitors. My novel required a more private crime scene. To find one I knew I would have to head down a trail.

The South Kaibab and the Bright Angel trails are the Canyon’s most popular, best maintained, and safest. They’re also mobbed. Luckily, there are quieter trails, unpatrolled by rangers.

When veteran Grand Canyon hiker Robert Spangler decided in 1993 to murder his wife, he took her on the Grandview Trail. After a few days of camping below the rim, the couple stopped for a break just above the most formidably steep rock layer in the Canyon, the towering Redwall. There Spangler shoved her over. Then he hiked back up the Grandview Trail, drove to Grand Canyon Village, and waited in line at the Backcountry Information Office to report her supposed accident to the rangers. He might have gotten away with it if a local sheriff hadn’t noticed that his previous wife had also died mysteriously. (Spangler eventually confessed to both those murders and more. For full details on Spangler’s fascinating and odious career, I recommend Robert Scott’s Married to Murder.)

My son on the Grandview Trail, which was built by miners in the 1890s to accommodate their pack-mules.

But the Grandview Trail, while truly scenic and impressively steep, failed to suit me. My plan for the novel involved a resort development that threatened to devastate the Canyon’s water supply. The Grandview Trail, however, is bone dry. It has no water supply to protect.

So the next day we tried the Hermit Trail, at the far western end of the park’s access road.

Our efforts were immediately rewarded. Just steps past the trailhead, we made the delightful discovery (aided by our guidebook) of countless fossils of the shells of brachiopods, ancient marine animals. Millions of years ago, these creatures flourished in shallow seas over what today is the Arizona desert. Today they’re a powerful symbol of the transformative ebb and flow of time in the Grand Canyon.

Like most writers, I love a good symbol.

After an hour, most of the family turned back, and I hiked on with just my father. We saw few other people but plenty of wildflowers and lizards. The Hermit Trail leads to various water sources, including Santa Maria Springs and Dripping Springs. Its greenery adds life and color to the views.

All that I needed now was a locale suited to murder—that is, a cliff. After a few hours of hiking, I found it. The branch trail that leads to Dripping Springs runs over a ledge amid a rock structure knows as an amphitheater, a long curved cliff-face that marks the terminus of a side canyon.

My father and I stepped to the edge. The sheer red cliffs plunged deep into the canyon’s shadows. A bird, some carrion-feeder, maybe a condor, wheeled far below.

Just the place for a murder. Now all I had to do was write it.

*****

Formerly an editor and writer for Frommer’s travel guides, Jeff Soloway is now an executive editor in New York City. In 2014 he won the Robert L. Fish Memorial Award from the Mystery Writers of America. His Travel Writer mystery series is published by Alibi, Random House’s digital imprint for crime fiction. The second novel in the series, THE LAST DESCENT, which takes place in the Grand Canyon, just came out.

- ITW Presents: The Breakout Series - April 25, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: THE GARDEN GIRLS by Jessica R. Patch - April 25, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: AN INCONVENIENT WIFE by Karen E. Olson - April 25, 2024