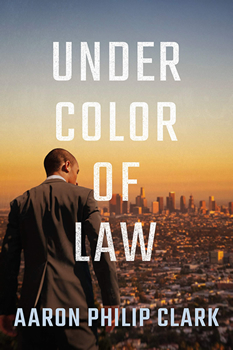

Under Color of Law by Aaron Philip Clark

In UNDER COLOR OF LAW by Aaron Philip Clark, the body of a murdered Black police academy recruit has been found in the Angeles National Forest. The case may have racial implications, so the LAPD bosses assign Black detective Trevor “Finn” Finnegan the most troubling case of his career.

Finn knows that to catch the killer, he must follow the evidence no matter where it leads. He scours the underbelly of a volatile city where power, violence, and race intersect. But it’s Finn’s past as a beat cop that may hold the key to solving the recruit’s murder. This could lead to the end of Finn’s career. Or worse.

Even though I usually prefer a dead body in the first few sentences of a crime story, author Clark got the smell of charcoal, mesquite and grilled meats along with the promise of cold beers. I asked him to talk a bit about how he uses sensory details in his writing.

“My writing style,” he says, “varies slightly from book to book, depending on the character’s POV. In Finn’s case, he studied visual arts, so he’s developed a strong keenness on his surroundings. He analyzes and deconstructs everything. As a police officer, those skills are heightened. So while riding through LA, he’s an antenna, picking up all types of frequencies. I particularly like to write about scents and odors, which can be very telling.

“One of my favorite books, A Voice Through A Cloud by Denton Welch, is told through the POV of a character confined to a bed. The man relies on his senses to decipher what’s going on around him and to him. Welch uses sensory impressions to paint a picture for the reader. He describes everything, sometimes to the smallest detail. While I strive for some measure of that, I struggle to capture what things sound like. I sometimes can’t find a description that feels true. Describing the sound of metal scraping against stone may not be challenging, but someone sinking in quicksand, begging to be saved, would have a distinct sound—the gradual sinking and the mutters or screams of the doomed person—and that’s not easy to describe, viscerally.”

There are many LA-based crime stories. So what makes Finn’s LA different than all the others?

“The novel is told through Finn’s POV,” Clark says. “He’s the type of character I haven’t seen written about in crime fiction. He’s a Black man who grew up in suburban LA and learned to fear the city from watching the news and seeing his father, an LAPD officer, come home with bruised knuckles and blood on his shirt. As a suburban kid, he existed in a bubble. It isn’t until Finn becomes a police officer that he’s forced to travel neighborhoods he never experienced in his youth. He develops a deep love for those neighborhoods and residents, and throughout the novel, he explores that love through memory. It’s an approach that puts the reader in Finn’s shoes, not only witnessing the horrors rife in the city but also its beauty.”

Clark tells Finn’s story during two different times of his life and uses the past and present tense. What are the advantages and disadvantages to that approach?

“The past often informs the present,” he says. “Not to sound too philosophical, but as Faulkner said: ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ For Finn, he’s somewhat stuck in the past, psychologically and emotionally. It’s where much of his trauma took place, and trauma doesn’t adhere to time. It can be raw, as if it happened days ago, rather than years.

“Playing with time can be fun but also daunting,” Clark admits. “It’s tricky when crafting a memory in first-person, present-tense. It’s all about placement, so the cadence of the primary story isn’t disrupted.”

Speaking of time, I asked why UNDER COLOR OF LAW is set in 2014 and not 2020.

“2014 was an interesting time for law enforcement and the country,” Clark says. “An NYPD officer had choked Eric Garner to death, and it was captured on camera. Michael Brown had died in an altercation with police in Ferguson, Missouri, and Black Lives Matter was moving from a rallying cry to a movement. It was very much the tipping point, and I wanted to capture that period. Now, fast-forward to 2021, and things don’t look that much different. Perhaps that’s the underlying tragedy in the novel? Nothing changes except the years.”

It’s clear Clark sees the power of crime fiction as social commentary. Why is that important to him?

“My approach to writing always begins with the story,” he says. “I think the social commentary part comes naturally. In UNDER COLOR OF LAW, it would be odd having a Black detective not reflect on the protests for police reform and accountability. When I read police procedurals with premises set in the present-day that omit critical issues that pertain to the characters’ jobs as police officers, it just feels undercooked and skewed. While writers may want to avoid these topics, I can say firsthand that police officers often talk about them privately. While in the academy, I came across three senior officers debating the use of the chokehold that killed Eric Garner. One officer was defending its use, despite LAPD having banned its use as a restraint. When they saw me, they stopped talking, threatened to tell my drill instructor I wasn’t where I was supposed to be, and directed me elsewhere. Their conversation was only one of the many I’d hear in which officers discussed race, policing, and politics. There are no apolitical cops—they’re human beings with strong opinions and biases, unconscious and blatant. The challenge is keeping their beliefs from spilling into their interactions with the public.”

There’s so much father/son material in this book—and Clark dedicated it to his dad. “My father was a therapist,” he says. “And he had a massive library. It was an incredibly diverse collection of books: literature, autobiographies, biographies, theological texts, politics, American history, psychology, and the social sciences. I have fond memories of going into his study and randomly picking a book and reading it. Sometimes I had no clue what I was reading, but if it was interesting, I kept at it. I can say I learned a lot about brain development pretty early in life. I think those early experiences helped shape my love for reading and, subsequently, writing.”

Why do readers never tire of the themes of atonement and redemption?

“People want to believe change is possible,” Clark says. “It speaks to the human spirit, the need to believe that our actions don’t define us—that we can be greater than the worst thing we’ve ever done. It also makes for strong characters. If a character has to overcome something challenging—emotional, physical, or otherwise—it creates conflict and tension. If you pair that with solving a crime, you have the quintessential recipe for detective fiction.”

I had to ask: Finn mentions Columbo as one of his favorite shows. (It’s one of mine, as well.) What’s Clark’s favorite episode and what other TV shows had an effect on his writing?

“I loved Columbo growing up!” he says. “It was one of the shows my father and I watched all the time. Putting it in the novel was an ode to my dad. One of my favorite episodes is Butterfly in Shades of Grey. William Shatner stars as this powerful and conniving father hell-bent on keeping his daughter’s manuscript from being published. Second to Columbo is Homicide: Life on Street. Andre Braugher’s portrayal as Detective Frank Pembleton is brilliant. The show felt authentic in a way other cop shows around that time didn’t. I also love Boomtown, Southland, and Luther —all great police procedurals that feature compelling characters.”

Finally I asked Clark to put together his dream panel for ThrillerFest—who would be on the panel, why, and what would the topic be?

“Maybe this is too many authors for one panel,” he says, “but I’d take any combination of the following: Rachel Howzell Hall, Tod Goldberg, Walter Mosley, Steph Cha, Ivy Pochoda, Nina Revoyr, Naomi Hirahara, Denise Hamilton, Gar Anthony Haywood, Gary Phillips, and Michael Connelly. I admire how each author captures an aspect of Los Angeles, often building upon the city’s history and examining something that’s been forgotten, or in some cases, erased from collective memory. Listening to them discussing writing about place, memory, and the true crimes and/or events that inspired their work would be interesting.”

That’s not too many authors, but to paraphrase Sheriff Brody from Jaws: We’re gonna need a bigger table.

*****

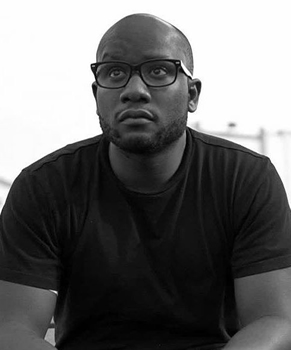

Aaron Philip Clark is a novelist and screenwriter from Los Angeles. In addition to his writing career, he has worked in the film industry, higher education, and law enforcement.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman - September 30, 2022

- Homeland Insecurity by J.L. Abramo - August 1, 2022

- Unruly Son by Neil S. Plakcy - May 31, 2022