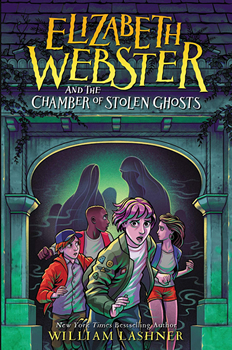

Elizabeth Webster and the Chamber of Stolen Ghosts by William Lashner

“Ghosts,” my grandfather often says. “Can’t live with them, can’t make any money without them.”

Elizabeth Webster is not your average seventh grader. Honestly, she’s not your average anything. What she is, though, is the youngest member of Webster & Spawn, a law firm for ghosts—and whatever other supernatural creatures can afford their legal services.

In this final book of the Elizabeth Webster trilogy, ELIZABETH WEBSTER AND THE CHAMBER OF STOLEN GHOSTS, our heroine finds herself dealing with yet another paranormal mystery—ghosts are disappearing. And not in the healthy, passing into the light sorta way. Someone is kidnapping—ghostnapping, more accurately—beloved and not-so-beloved ghosts.

But who? And to what end? It’s up to Elizabeth to find out—but that’s not where her role ends. Once she knows the villain, she has to collect evidence, interview witnesses, create a case, and sue for the ghosts’ release in the Court of Uncommon Pleas.

Difficult, yes. But for Elizabeth Webster, it’s just another hauntingly typical case at the law firm of Webster & Spawn.

Author William Lashner was kind enough to sit down with The Big Thrill and discuss all things Elizabeth, friendship, and authorial obligations. (That last one is not nearly as tedious as it sounds—so stay with us!)

This book has more adult themes in it than I expected for middle grade. It reminds me of some of the books that deeply impacted me when I was reading middle grade—books that addressed topics like loss, death, or unhealthy relationships. In that vein, your note to The Big Thrill mentioned obligations in writing for middle graders. Could you expand on that?

With middle grade, I felt like I had a different obligation to the kids than when I was writing adult books. I was conscious of the choices that kids have and what goes into those choices. In the mysteries that I used to write for adults, there was a sense of there’s only so much you can control. It’s a little like China Town—you know, “Forget it, Jake, it’s China Town.” And I didn’t want to do that at all. I wanted to make sure that the readers felt that my characters were empowered to make their own choices. And I have strong ideas about freedom, and so that became a theme in all three books: the freedom that Elizabeth has to make her choices, whatever those choices are.

When I decided when I was going to write this, I wasn’t going to write down to anybody. I was going to be aware of certain limitations, but I remember reading The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman, and his vocabulary was not watered down. And I thought, okay, so I don’t have to water down my vocabulary so much, and I’m not going to write down to anybody. Middle school is such a big period of you discovering yourself and the world and your power. I didn’t want to limit what the readers could talk about.

Right, kids are constantly having to deal with difficult things. It’s great that you wrote a book that doesn’t shy away from hard problems, where your readers can see some of their own issues solved by a character that they can look up to.

When I wrote this, I originally wrote it as young adult—they were in high school. But my agent thought the market was better for middle school.

One of the things my agent said was, Let’s avoid the romance stuff. And I liked that, I found it liberating. It changed things, because when you’re writing a book, generally, you have friendships. But they’re taken for granted because you’re really reaching for the romance. When you take out the romance or the possibility of romance, suddenly the friendships become much more important. And that became one of the big themes in this third book: the friendship between Elizabeth and Natalie. I wanted to give them a little bit of distance and difficulty. Which opened up for me the story at the orphanage.

Which was horrifying. Everything about that, from start to finish, was “Oh no. Oh no. Oh no.”

That was a story that I created to talk about Elizabeth and Natalie’s friendship. That’s what it was there for. How, in the middle of it, Elizabeth and Natalie are able to break away and come to an accommodation: they don’t have to control each other or have expectations, they’re just going to be friends forever—or until high school.

Something I found interesting was the idea of identification in a friendship. When the Mel and Juniper plot line started off, Mel was adventurous and brash while Juniper was nervous and hesitant. And when they started changing roles, Mel had a moment of reckoning where she had to come to terms with the idea that her friends will change, and it’s okay. And also like the idea that, to try to put it in her voice, “It doesn’t matter who I am in relation to my friend. Her being adventurous does not make me not adventurous. I am me and she is her and no matter what, we are friends—whoever we become.”

Right. That change was exactly what I was working for from the beginning. And there was that moment when Mel says she wants to go back to a world that makes sense, and Juniper doesn’t see the world that they were living in as making the same sense that Mel did. There is that change, and Mel’s so upset by it, she uses the words “pissed off.” [My editor and I] had a long discussion about if those words should be kept in, and I said at that moment the language has to be strong enough to pop the reader out in a way, you know. “Oh my gosh, this is The Moment.”

I would love to see a wrap-up book. Elizabeth as a lawyer in her 30s or 40s. Or Grandma Elizabeth, running the firm, and what she would be like at 70 with a couple of wild grandkids.

One of the things that I like about how the book ended is that Elizabeth started feeling her own power to make her own life. I’m not sure where she would go, to be perfectly honest. I mean, it’s not like I have control. It’s Elizabeth. She has her own life, and I don’t know what choices she’s going to make. I would love to see it.

*****

William Lashner is a former criminal prosecutor with the Department of Justice in Washington, DC and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His novels have been published worldwide and have been nominated for two Shamus Awards, a Gumshoe Award, an Edgar Award, and been selected as an Editor’s Choice in the New York Times Book Review. When he was a kid, his favorite books were The Count of Monte Cristo and any comic with Batman on the cover. Elizabeth Webster is his first series for kids.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- ITW Presents: The Breakout Series - April 25, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: THE GARDEN GIRLS by Jessica R. Patch - April 25, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: AN INCONVENIENT WIFE by Karen E. Olson - April 25, 2024