Africa Scene: Joanne Hichens

Getting Under the Skin of Her Characters

Joanne Hichens is an author and editor who lives in Cape Town, South Africa. She has broad interests, having written young adult novels and recently published a moving memoir titled Death and the After Parties. In adult fiction, she’s written several thrillers and edited a number of short story anthologies, including two South African crime-thriller collections—Bad Company and Bloody Satisfied.

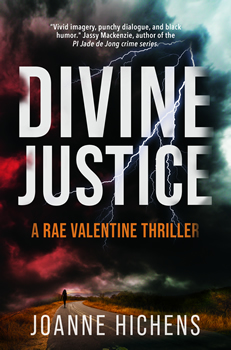

In her crime novels, Hichens features Rae Valentine, an ex-junkie amputee turned PI and motivational speaker. I find Rae one of the most interesting protagonists of the South African crime genre, and I’m delighted that Catalyst Press has just published the first Rae novel, DIVINE JUSTICE, in the US.

Publishers Weekly loved it, saying that “Staccato prose moves the action along at machine-gun pace reminiscent of classic hard boiled mysteries…” and that “…fans of George V. Higgins and James Ellroy are sure to have a blast.” This is a book to kick off a great 2021 of thriller reading.

In this interview for The Big Thrill, I chat with Hichens about Rae and the development of DIVINE JUSTICE.

Rae Valentine is a wonderful character. An amputee who lost her leg to drug addiction, she has been tortured and nearly raped, but has “pulled herself up by her armpits.” Although an attractive woman, the story begins with her being dumped by Anthony Durant, her boyfriend and partner in a private investigator business. Durant is quickly pulled out of the story by being arrested on a trumped-up charge, leaving her to run the business with just the third partner, who is an alcoholic. And it gets worse for Rae from there.

How did you conceive Rae, and how did you research the details of how she would operate with her disability?

Rae was a bit player in another novel I’d written and at the time, even then, I wanted to explore her character as an ex-junkie, an amputee, and a woman of color more fully. She has issues with her past as she was fostered and brought up in a privileged home. She’s an unconventional sleuth. A city gal. She lives squarely in the modern world, in an apartment in Cape Town, at the foot of the famed Table Mountain. She loves the natural beauty of the city, but is also appalled by the poverty, by the double standards.

Rae shot up heroin once too often between her toes, lost her leg, went into rehab, and reformed. As I was writing, it dawned on me that such physical disability is particularly restrictive and I needed to do research, but I also really imagined myself into the body of Rae. I hopped around and used crutches to get a sense of what it was like to be without a leg. And, of course, I read plenty of accounts of the experience and talked to a number of people who are similarly disabled.

My strong view is that we’re all disabled in some way. The term more commonly and currently used is “differently abled.” This rings with truth, as every one of us has an issue, physical or mental, that could be labelled a “disability”—whether one wears glasses, or suffers bipolar, or is a recovering alcoholic (as so many fictional cops and PIs are), we each have an albatross around our neck—now, it remains how to deal with it. How to accept disability, cope with being “differently abled,” and not allow it to affect one’s competency.

Cape Town, where the majority of the action takes place. Photo taken from the top of Table Mountain at night.

DIVINE JUSTICE was released in South Africa some years ago, but its themes seem even more relevant today. An extreme religious-right conspiracy with a White supremacist agenda is straight out of last month’s US headlines. Coming closer to home, was the concept inspired by the antics of Eugene Terre’Blanche and his Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB)?

Indeed it was. As well as by other right-wing groups, and also by the growing neo-Nazi movements in general.

To give a little history, particularly in the 1980s, armed groups emerged as the authoritarian apartheid regime struggled to maintain its legitimacy in the face of widespread internal resistance and international diplomatic and investment opposition. One group, the AWB, built considerable conservative White Afrikaner support, attracted international attention, and committed acts of violence that threatened a race war.

The AWB believed, fanatically, in their duty, as God’s Chosen, to protect what they considered their birthright and their culture. Their members threatened to fight for their own Volkstaad, to provide Whites with a homogenous “homeland.” They paraded in khaki uniform, on horseback, through the streets of small towns, draping their version of the neo-Nazi flag as well as the old South African flag on their shoulders, and they touted rifles and made threats.

The parallels to the Proud Boys are distinctive. The brazen way Trump supporters waved their Confederate flags outside and inside of the Capitol during the US insurrection is eerily similar. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

At the time I first penned DIVINE JUSTICE, many post-apartheid crime writers were tackling the dynamics of a new racial order through police detective pairings of mixed race, or creating precincts of Black and White officers. I wanted to do something different. I wanted to expose the “hate” that still festered, in some quarters, like a boil waiting to be lanced.

On the back of general and growing strife in the country, I created a White supremacist group, “The Core,” loosely based on neo-Nazism and using the AWB as context. Warped by their own particular brand of racism, “The Core” is not only a threat to private investigator Rae Valentine, who gets drawn into their web, but the group are seen as a threat to national prosperity as they carry out their malicious deeds—bombings, and drive-by shootings of immigrants on the streets.

The Boyz, part of “The Core,” are losers—vicious thugs who hardly pretend even to themselves that there are true political and religious motives behind their mayhem. They remind me strongly of the Terre’Blanche era to say nothing of the Proud Boys of today. But JP, Christoff, and Alex are real personalities, if unpleasant ones. How did you get under the skin of young men like them?

This is the job of the writer. Using the imagination and allowing imagination to bloom, and also tuning in to empathy, a writer gets under the skin of all sorts of different characters. As for these men, they perceive themselves as redundant, as passed over, as being placed second to the immigrant. They are manipulated by others—a prophet, a criminal—to the point where their grievances are so heightened that they turn to violence.

A glimpse of the AWB, a White supremacist group active in the ’80s, with their adapted neo-Nazi flag.

To get into the heads of these characters, I imagined myself as disenfranchised, as bitter, as angry, connecting with those emotions (we all have them in some measure), and I then allowed myself to go into that territory of criminal behavior—what violence would I perpetrate? I think we’re afraid of facing the violence in our own heads, but it exists there… and by connecting with it, I’m able to bring that viciousness to my characters. I recognize that resentment and anger, fueled by a measure of idiocy, can easily devolve to criminality.

A major theme in the book is that a group of fanatics—be they religious, White supremacists, or extreme right or left wing—can be manipulated by clever people for their own ends. Would you comment?

We’ve seen a great example of this just recently, particularly with the storming of the Capitol. Trump, the arch manipulator, used the kind of language in his White House address that gave his supporters “permission” to take things into their own hands. Indeed he specifically told his supporters to march on the Capitol, even saying boldly he’d be there with them. Yes, manipulators are clever, but more instinctively they target groups of the disenfranchised or weaker, unstable people susceptible to whatever is their message, driven home in language of intolerance and division and essentially—hate. They are out of touch with reality, becoming more deluded as they spew untruths of conspiracy theories and downright lies. As American historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat has said, this type of authoritarian leader “wants us to lose our faith in our ears and our eyes, what we read and what we observe, so that we can be more dependent on him.”

Rocco Robano is the puppetmaster of the Boyz, and we immediately know that his interest in the pharmacist and part-time preacher Heinz Dieter has nothing to do with religion. Clearly he’s after money, but there’s much more to him than that, and none of it is pleasant. You give him a powerful voice in the thriller—much of the story is from his point of view, perhaps as much as from Rae’s. Why did you decide to tell the story in that format?

I’ve always loved reading thrillers in which the bad guys have a voice. It adds a wickedness to the writing. And these thrillers and crime fiction novels are underscored by a black humor which appeals to my sense of the morbid and the absurd.

Writers like Elmore Leonard and Carl Hiaasen often write from the perspective of the bad guy. I enjoy a story that unfolds from different angles, from different points of view. I’m less interested in more traditional whodunits written from one perspective, unless the character is superb, and here I’m thinking of how seductive is Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther. But certainly the darker side of life appeals to me, and to do it justice, I want to show it.

As a writer, putting myself in the head of a mad fanatic such as Heinz Dieter, who spews the prophecies of Nostradamus and warns of an Apocalypse, was challenging, but it also called for insight as to how the fanatic was formed, how the fanatic or the right-winger came to believe his extremist ideology, always remembering that it doesn’t come from nowhere. I had always to remember that the rotten, corrupt leader exploits and manipulates people for his own ends. As for Rocco Robano, he is malicious, malevolent, a psychopath—the ultimate puppetmaster.

Fire on Table Mountain, a sign of the Apocalypse, according to Pastor Heinz Dieter. (Photo credit: Bryan De Kock)

The climax occurs when the characters all meet at a farm on the Orange River in the middle of nowhere. By now Dieter is completely mad, the Boyz are out of control, and Rocco throws Rae into the mix to try to handle Dieter, first confiscating her prosthesis. What could possibly go wrong? Well, a few ostriches for a start… It’s a great thriller climax! How did you come up with that scene?

I let my imagination run riot! I’d been down the Orange River myself on a canoe, so I knew the terrain. Situated between South Africa and Namibia, it’s a fabulous stretch of river which offers white-water rafting. At night we slept on the banks of the river, under the stars. It was tremendous. And I remember thinking this would be a great spot for a grand finale. Also, I wanted to turn the idea of an “African farm” on its head. An African farm is not always a calm, beautiful place. An African farm, in this case, is the culmination of all the hate and brings it to a head.

We hope to see more of Rae. Will you be bringing her back in the future?

I’m hoping the sequel, Sweet Paradise, set in a psychiatric clinic (I worked in a psychiatric clinic as a therapist for a number of years, so much of it is based on my own experience) will be published by Catalyst Press, and I’m working on a third Rae Valentine thriller.

I’ve also written a memoir, Death and the After Parties. My husband died of an unexpected, massive coronary a number of years ago, so I turned my attention to writing memoir. Life throws curve balls! But I’m back to crime writing and loving it.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024