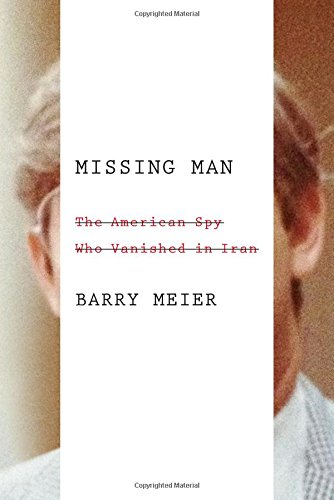

Missing Man by Barry Meier

The Haunting Tragedy of an Abduction in Iran

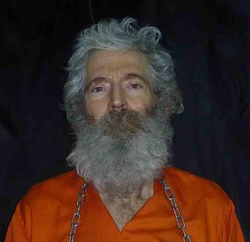

In December 2011, a disturbing video hit the news. In the brief clip, an American in his sixties, Robert Levinson, missing since March 2007, said to the camera: “I have been treated well, but I need the help of the United States government to answer the requests of the group that has held me for three-and-a-half years. And please help me get home. Thirty-three years of service to the United States deserves something. Please help me.”

Our media has since overflowed with horrific videos of Americans imprisoned in the Middle East. But Levinson is an unusual case. He went missing while on Kish Island off the coast of Iran, his precise status within the American intelligence community is debated to this day, and he remains missing. His wife, seven children, his many friends and former colleagues, all are scarred by the mystery of Robert Levinson.

In MISSING MAN, the nonfiction book published by Farrar Straus and Giroux, award-winning journalist Barry Meier delves deep into that mystery, painting a vivid—and troubling—picture of an American intelligence community that ultimately failed Levinson through timidity, ineffectiveness, and political infighting and fingerpointing. While ingenuity and loyalty to comrades is a central theme of TV shows like Homeland, saving one’s job trumped saving Levinson’s life at the real CIA.

“By not standing up, they basically doomed him,” says Meier of Levinson. “He was road kill.”

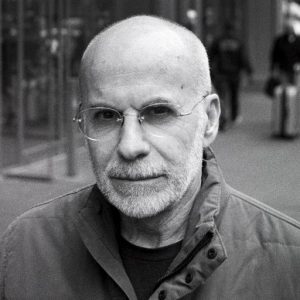

A Pulitzer finalist at The New York Times, Meier was looking for his next big story in the fall of 2007 when he happened to see a Financial Times article on Levinson’s recent disappearance. Intrigued, the reporter started digging. His awards were won because of Meier’s investigations into the dangers of various drugs and medical devices, including a defective heart device. He was the first reporter to shed light on the abuse of Oxycontin. While these medical-journalism credentials might seem irrelevant to writing about a man snatched in Iran, there is significant overlap. Before disappearing, Levinson spent years gathering information on cigarette smuggling as a private investigator; Meier has sources in the tobacco industry. In fact, Levinson ostensibly traveled to Kish Island in 2007 to look into a cigarette-smuggling case in Iran for a client, British American Tobacco.

It wasn’t true. Levinson went to Kish to meet with an American who fled to Iran after assassinating an Iranian exile in Washington, D.C. The man’s name is Dawad Salahuddin; Levinson got in contact with him through a journalist and mutual friend. Levinson hoped to “turn” Salahuddin. The two did meet at a hotel on Kish, a free-wheeling island where Levinson could travel without needing to get an Iranian Visa. But after the meeting, no one in the U.S. knows what happened except that Levinson disappeared.

As Meier reports, Levinson, a retired FBI agent, held a consultancy contract with the CIA at the time he went missing, a fact denied for years and then, once confirmed, withheld from the American public in hopes of saving Levinson’s life. But did his CIA contacts know why he went to Kish Island—or was it Levinson’s freelance fishing expedition to reel in Salahuddin (“a supreme sociopath,” says Meier) in hopes of shaking loose more money from the CIA on his next contract?

It’s no accident that this sounds like a John le Carre book. Meier is an admirer of le Carre’s work and early in his career wanted to write spy fiction. In MISSING MAN, Meier’s years of reporting–interviews with dozens of key players and access to Levinson’s emails–fuel a rich narrative populated by Russian gangsters, FBI and CIA agents, ethically challenged journalists, and icy diplomats. The book is “chock full of intriguing characters,” says Meier.

It is in his description of Levinson, a warm-hearted, “morally complex” man of drive and determination tormented by financial pressure, that the story becomes heartbreaking. Levinson is one of several aging professionals in MISSING MAN desperate for a big win. Levinson was not a trained spy nor in any way prepared for Iranian security forces. After retiring from the FBI, he struggled in the private sector for nine years. “He had a sense of pride, he wanted to be a player again,” says Meier. Anne Jablonski, the CIA analyst and member of the agency’s “Illicit Finance Group” who “ran” Levinson, was an old friend he called “Toots.” She was forbidden to send clandestine operatives to places like Iran and ended up losing her job over the Levinson scandal. She “was very ambitious,” says Meier, who met her as part of his reporting after she was fired. Ultimately, the CIA “had no moral fiber.” By denying that Levinson was gathering information for a CIA unit until the Associated Press broke the news in 2013, the agency made it that much more impossible to secure his release. (The CIA has paid the Levinson family a reported $2 million to prevent a lawsuit; the agency also refused to cooperate with Levinson in any way, even denying his request to set foot in Langley.)

Another jolt in reading MISSING MAN is discovering how ineffective the FBI (“the agents used were not the best or the brightest”) and the diplomatic community were in finding out what happened to Levinson on Kish, or later in Iran, and then negotiating for his release or swap. The United States had no success in discovering the details of his arrest or imprisonment, ignoring a mysterious email early on that could have provided answers, and reveals a complete lack of sources in Iran or any ability to pressure Iran’s government. “The book sheds a lot of light on how we operate and how a country like Iran operates,” says Meier. “They were always playing with us.”

The author of MISSING MAN says he was “shocked” that Boeing recently made a $25 billion deal to sell jetliners to Iran without the U.S. using this as an opportunity to get answers about Robert Levinson for his devastated family.

“We are in a twilight period,” says Meier.

*************

Barry Meier, a reporter for The New York Times, has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and is a two-time winner of the George Polk Award. His reporting at The Times has concentrated on the intersection of business, medicine and the public’s health. Meier is the author of an e-book, “A World of Hurt: Fixing Pain Medicine’s Biggest Mistake” (The New York Times, 2013), and Pain Killer: A ‘Wonder’ Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003). Before he joined The Times in 1989, Mr. Meier worked at The Wall Street Journal and at New York Newsday. He lives in New York with his wife and their daughter.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018