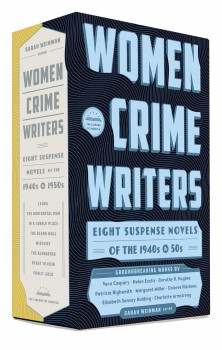

Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s and 50s, edited by Sarah Weinman

The 1944 film Laura is a noir classic, cherished not only for its haunting score and performances–alluring Gene Tierney, acerbic Clifton Webb, and relentless Dana Andrews–but also for the chills of the brutal murder at its core. Less well known is the 1942 detective story the film was based on, written by Vera Caspary. It’s a tense read, more nuanced than the film, with daring point of view switches and well developed characters, set in a world of newspaper-columnist divas, impoverished fashion models, striving ad executives, and ice-cold heiresses.

This may change, now that Caspary’s novel has been brought to light as part of the stunning collection Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s and 1950s, published by the Library of America and edited by Sarah Weinman. The other chosen authors: , , , , , , and

Weinman, a crime fiction aficionado, selected the “top of the class” women writers of suspense of that era: “They had good sales in hardcover and paperback, excellent reviews, high regard among their writer peers.” This is not Weinman’s first foray into earlier decades. She edited Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, published by Penguin Books in 2013 and nominated for an Anthony Award. When reading through the work she gathered for Women Crime Writers, she was struck by how universal and timeless the stories are. “Mothers still do everything to protect their children, still fear murderous men, still struggle with expectations placed upon them by society, family, peer groups, and the like,” she says.

On the Library of America website, each story is enhanced by a contemporary writer’s appreciation, offering her own textured perspective. Caspary, author of Laura, could create such a convincing 1940s Manhattan world because she lived it, as a journalist and copywriter. Writes Sara Paretsky: “Like her heroine, Caspary carved a major professional life for herself at a time when it was both rare and hard for women to occupy that space. Coming of age at the end of the First World War, she moved to New York in 1925 and lived a Gatsby kind of life of wild parties (she was thrown into a china closet during one of them) and lovers. At the same time, she worked hard, built a career, and believed, at the end of her long life, that she had done what women are so often told they can’t: had a highly successful career and a fulfilling private life.”

Another gripping story in the collection is In a Lonely Place, written by Dorothy B. Hughes and also the source of a famous film that takes considerable liberties, in this case directed by Nicolas Ray and starring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Graham. The novel In a Lonely Place is, quite simply, terrifying. In her introduction, Megan Abbott says, “While not the first serial killer tale, In a Lonely Place set up a template for hundreds to come, anticipating even Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952) by bringing the reader inside the killer’s fevered head. But, unlike Thompson and many later writers, Hughes directs her gaze inward only to then direct our gaze outward. She has in mind something larger—about the nature of sex crimes, but also about the complicated, freighted environment of America just after World War II. In fact, if you wanted one book to tell you about the consuming gender trouble and sexual paranoia of that moment, you could do no better than Hughes’s too long neglected masterpiece.”

Patricia Highsmith, best known today for The Talented Mr. Ripley, is perhaps the rock star of the eight. The release this month of Carol, based on another Highsmith novel, starring Cate Blanchett, will no doubt increase interest in the author even more. For Women Crime Writers, Weinman selected The Blunderer, written early in her career. The story, like so much of Highsmith’s work, is “a meditation on obsession and guilt,” says Karin Slaughter in her introduction. When a man’s hands close around the throat of his nagging wife, he’s aware “only of pure joy.” Declares Slaughter: “This violent, startling outburst is pure Highsmith.”

Certainly anyone expecting a “softer” take on crime in these stories is in for a shock. In fact, Weinman says, “These women in large part wrote without much in the way of sentimentality. Tell a good story, tell it well, and whether or not there are noble romantic characters is less important. Whereas the men popular of the time relied heavily on sentimentality, whether they admitted to do doing so or not. Philip Marlowe is a romantic. Mike Hammer is a cartoon character puffing up his, and his readers’, masculinity. Lew Archer had disappointed romance all around him.”

In some ways, ironically, it was easier for women to get their crime fiction into print in the 1940s and 1950s than in 2015. Weinman says: “There were so many publishers to choose from! Now mystery and suspense publishing has contracted considerably.”

With women’s crime series and standalone novels flying high on today’s bestseller lists, attention is obviously being paid. “Overall things are better than they were, but we still have a long way to go,” Weinman says. “Too many publications still seem to favor reviews of crime novels by men more than women, though more seem to be aware of the problem, thanks to Sisters in Crime and to some extent (at least in an overall capacity) VIDA. What I know is there is a freshness and vitality to crime writing by women that marks their books as distinct and interesting, and so of course I keep gravitating to them. 2016 will see some really strong books. There still needs to be more voices, always. ”

*****

Film Forum in Manhattan has programmed a series revolving around Women Crime Writers from Dec. 11th to 17th, including Laura, In a Lonely Place, Strangers on a Train and The Reckless Moment. Sarah Weinman, Megan Abbott, and Library of America Editor in Chief Geoffrey O’Brien will make introductions to the films. For more information, go to http://filmforum.org/series/women-crime-writers-series.

Sarah Weinman is News Editor for Publishers Marketplace, where she works on Publishers Lunch, the industry’s essential daily read with more than 40,000 subscribers, and the editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, published by Penguin in 2013. She also contributed a chapter to the NYT bestselling serial suspense novel Inherit the Dead.

Sarah Weinman is News Editor for Publishers Marketplace, where she works on Publishers Lunch, the industry’s essential daily read with more than 40,000 subscribers, and the editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, published by Penguin in 2013. She also contributed a chapter to the NYT bestselling serial suspense novel Inherit the Dead.

To learn more about Sarah, please visit her website.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018