Features Africa Scene: Kwei Quartey

A Missing Persons Case Stretching from Ghana to Libya

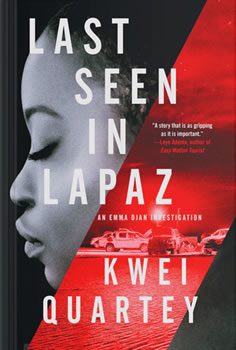

Kwei Quartey has just released the third novel in his private eye series set in Ghana, featuring PI Emma Djan. The first book in the series, The Missing American, was a 2021 Edgar Award nominee, and winner of the 2021 Shamus Award for Best First PI Novel. The sequel, Sleep Well My Lady, was a nominee for Best Novel of 2021. The new novel, LAST SEEN IN LAPAZ, easily lives up to the standard of its predecessors.

Ngozi, the daughter of the erstwhile Nigerian high commissioner to Ghana, vanishes from her parents’ home. The last time she’s seen is at a supermarket in the Ghanaian town of Lapaz by an acquaintance. Has she run away with a young man she knows, Femi Adebanjo, or has she been kidnapped as her parents fear?

When Emma is given the case to investigate, she discovers that aspects of it stretch from Ghana to Libya—and that it involves sex workers and people smugglers.

Here, Quartey tells us more about his latest release, LAST SEEN IN LAPAZ.

The new book seems to show Emma as more introspective. She has a serious boyfriend and wonders where the relationship is going; she loves her mother, but struggles with her controlling manner; she worries that she oversteps the mark as a PI or that she doesn’t do it well enough. Would you comment?

Yes, Emma is and has been maturing, expanding in knowledge and perspective. What dogs her somewhat is a complex insecurity over whether she’s quite “good enough” at her job. It seems to stem from never having had a chance to show her late father, due to his untimely death, that she followed in his footsteps as a homicide detective. Even more than that, Emma seems to be trying to prove to herself that she’s that good. In that zeal, she sometimes steps over a line during investigations beyond which her life could be jeopardized. Added to this is a taint of disapproval from the perspective of her mother, who appears to think her daughter could have a “better” and less dangerous job.

Detective Inspector Boateng (Diboat, as Emma calls him) is an amenable police detective, willing to work with Emma and her team and share information. It seems to work out pretty well. Given that the police seem to be overworked and lack resources in Ghana, is this a natural relationship between PIs and the police there?

According to the two Ghanaian private investigators that help me gather information for my novels, it’s a mixed picture depending on the particular individuals with whom they’re dealing. Some share information willingly, while others quite frankly dislike the PIs. The areas in which there’s mutual collaboration include tracking and tracing criminals to facilitate arrest, and kidnapping cases. However, it’s something of a “one-way street,”—for example, the PIs have a lot more to offer to the cops than the reverse. In one case I have personal knowledge of, the PI did all the work, including luring the criminal to a restaurant where the cops were waiting for him. So, the bottom line is that Emma definitely struck lucky with “Diboat.”

Femi Adebanjo is one of the main characters in the story. At the start of the book, he is shot dead but we learn his history as the book unfolds. An unsuccessful small-time crook in Nigeria, he joins his friend Cliffy as a recruiter of migrants to Europe, charging them fat fees for very little. However, he soon moves to managing sex workers in Ghana. One of his colleagues says that although Femi may love Ngozi, he loves money more. Is greed the basis of his character? There seems to be violence in there too.

Greed accounts for much of his character, but Femi also has the psychopathy of a personality disorder that began during his teens. He has superficial charm and glibness combined with narcissism. He lies and manipulates easily without any guilt or remorse, lacks concern for the suffering of others, and lacks impulse control, as manifested by his explosive anger and violence. He’s the kind of person who can suck you in without your realizing that you’re entering a dangerous web you might never emerge from.

Ben-Kwame is the son of one of the owners of the Alligator Hotel, a brothel. He is the enforcer, and enjoys the job of beating up the women and worse. In fact, his brutality and stupidity help Emma make progress with the case. Did you use the Alligator Hotel to show how powerless the women themselves are in the sex industry?

Yes, the Alligator Hotel, which is a real brothel in Accra, highlights one system of sex work in Ghana that is the most antiquated and most tied to tricking sex workers into indentured servitude laced with violence. The Alligator contrasts with a more modernized, independent type of sex work in which the women have more latitude in gaining clients through sophisticated sex websites and phone apps that facilitate direct interaction with the client without an intervening “pimp” or “madam” calling the shots.

Much of LAST SEEN IN LAPAZ is concerned with the human traffickers who “help” would-be migrants make their way from West Africa to Italy via Libya. One part of the book vividly details the journey of two migrants from Nigeria to Libya. How did you research this aspect of the story?

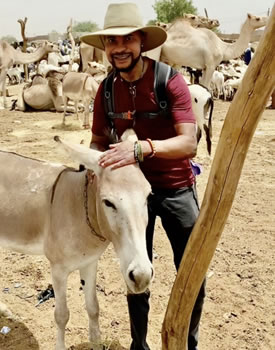

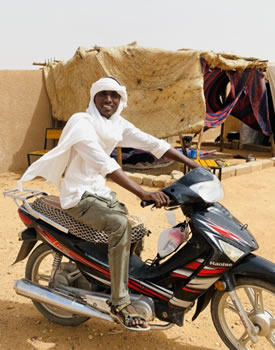

Kwei’s guide Ibrahim on the most-used form of transportation in Agadez. His headdress has no religious or ideological meaning—it’s protection against the stinging wind should a sandstorm occur.

That part of the story was indeed the most intensely researched in which I interviewed a dozen or so migrant returnees in Nigeria, the source of the migrants, and in Niger, the intermediate stop on the way to Libya, a truly harrowing and often horrifying and hazardous journey across the seemingly endless span of the Sahara Desert.

All the events in the novel from Nigeria through Niger to Libya are a combination of different experiences of the migrants I interviewed—to which I added the fictional characters—rather than one or two specifically. For instance, the women’s stories differed from those of the men in several ways, so I incorporated their narrative into the main female migrant character in the novel, and did the same for the males. For a paltry sum, I did assist one Sierra Leonean young man to get back to his home country from Niger, and he appeared in the novel as well. One of the book’s most painful scenes, which I don’t recommend to the squeamish, is taken directly from a secretly recorded video sent to me by a survivor.

Nigeria should be the powerhouse of Africa in terms of the size of its economy and its resources. Yet the picture we get from books set there is of a country so mired in corrupt practices and inefficiency that people there want to go anywhere else (Europe or elsewhere in West Africa). Is this your impression?

Nigeria should be a success story. Instead, it’s a disaster. Young Nigerians in particular are so desperate to get to a better life that they will do almost anything. So strong is the desire that there are even migrant returnees who are willing to make a second and even a third attempt to get to Europe. Ghana serves as the less expensive and less dangerous alternative destination for Nigerians.

What’s next? Another Emma investigation? A return to Darko Dawson? Or something completely different?

Next is the 4th Emma Djan Investigation called The Whitewashed Tombs, which centers around the present wave of anti-LGBTQ sentiment in Ghana, whose parliament is debating whether to pass a draconian law that will criminalize any form of gay activity or attempt to support or “promote” homosexuality. If the law passes, it will be possibly the most regressive piece of legislation in Ghana’s history.

Regarding Darko, barely a week passes in which a reader begs to have Darko back. I think I might do that in 2025.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024