Featured Articles Africa Scene: Fatin Abbas

Creating a Powerful Sense of Place

The year 2023 kicks off with a remarkable debut by Fatin Abbas, an author who will certainly have much more to tell us in the future.

Fatin was born in Khartoum, Sudan, but her parents were forced to leave Sudan when the military seized power there. The family settled in New York, and she received her MFA from Hunter College, the City University of New York. Her writing has appeared in Granta, Freeman’s, and The Nation.

GHOST SEASON, her first novel, is set in a fictional town near the border between Sudan and South Sudan, and as the war heats up again, the tension climbs. The sense of place is powerful, the characters superbly drawn.

Here, she tells The Big Thrill a little about her background and how it led to writing this compulsive novel.

Please share a little about yourself and your journey to writing GHOST SEASON.

I was born in Khartoum, Sudan. In 1989, Omar al-Bashir seized power in a coup, and a military-Islamist dictatorship took control of the country. I was seven. My father, who was an English professor at the University of Khartoum at the time, was a pro-democracy activist and political dissident. He was arrested within the first weeks of the dictatorship because of his opposition to the regime and spent a year in prison (between 1989-1990). Some of my earliest childhood memories are of going to visit my father in Kober Prison in Khartoum. He was, thankfully, eventually released without harm. But for obvious reasons, my parents felt that it was no longer safe for him or us to remain in Sudan. We landed in New York in 1990.

Becoming a novelist is very much tied up with these early childhood dislocations that began with the dictatorship, my father’s imprisonment, and our exile. I became consumed with writing as a child, soon after our move to the US. I’d fill notebooks and notebooks with stories. The stories allowed me to create fantasy worlds in which I could make a place for myself, when everything around me was new and strange—new country, culture, and language. Also, having a father who taught literature, a love of books and writers was always a big thing in my family. In New York and Cairo, where we also lived for a while, my father and I would often go on outings to bookstores. He’d buy me lots of books. So I grew up in a family with a deep reverence for literature and writers and for novelists in particular.

In GHOST SEASON, you depict the town of Saraaya vividly. Can you speak more about the setting of the novel and what inspired it?

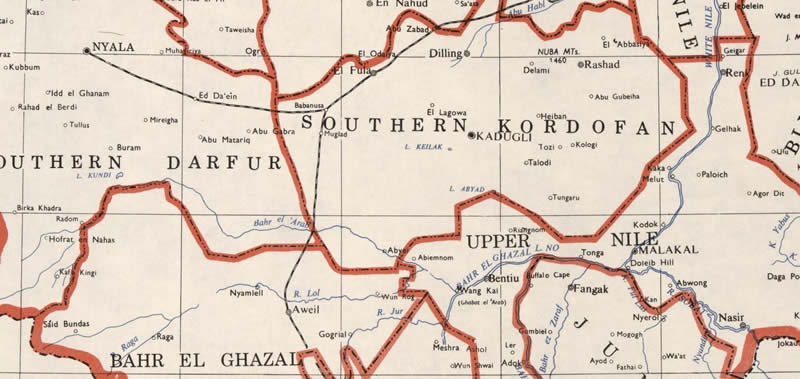

The town of Saraaya is fictional, though it’s inspired by a real place. In the mid-2000s, after graduating from university, I returned to Sudan and spent a year working for a small Irish NGO in Khartoum. Part of the job entailed traveling to and working in the town of Abyei, on the border of pre-secession North and South Sudan. Abyei became the inspiration for the town of Saraaya. But I decided to fictionalize the town in GHOST SEASON partly because I didn’t want the novel to be read as “ethnography.” I was aware that the place I was constructing in the novel is a fantasy, my own fantasy or projection of Sudan. So I decided to create a town that was fictional but had the feel of a real place, through which I could raise these questions about the nation-state itself as a fantasy, a projection, or a construct of the imagination. I wanted to play with the readers’ expectations: a Western reader might assume Saraaya is a real place, but a Sudanese or South Sudanese reader will probably know immediately that no such town exists on the border of North and South Sudan. I include some disfigured maps in the book; these are actual archival maps, and if you search these maps, you won’t find the town of Saraaya marked there. This is just one way in which I try to call attention to the “fabricated” nature of my own representation. The Sudan I have in my head is just one fantasy, one projection of many. There is no authoritative, definitive, or “authentic” representation of Sudan or South Sudan. There is only imaginative interpretation. I offer GHOST SEASON as one such interpretation.

Most of the novel is built around the characters at an NGO station in Saraaya. Dena is from Khartoum, but her parents moved the family to the US years before. She is making some sort of documentary, but although she’s a talented photographer, she has little real engagement with the local people. Alex is an American geographer tasked with making modern maps of the area but has little patience with, or interest in, Saraaya’s peoples. He relies on William, the Nilot translator, who is also the de facto manager of the NGO. William is in love with their cook, Layla, who is a nomad. The cast is completed by Mustafa, a young nomad boy trying to support his mother and siblings by doing odd jobs at the NGO and finding a more supportive family in the process. Why did you choose this particular cast of characters for your novel?

When I started writing the novel, the characters appeared and formed organically. In retrospect, I understand that they exist in this constellation for a reason. This is a novel about a non-biological family, a family made up of a group of individuals from vastly different backgrounds, ethnicities, religions, socio-economic and gender experiences. Through this constellation of characters, I think about community. How is community, a sense of family, formed outside of the bounds of blood kinship? Mustafa’s father is dead, and though Mustafa is a nomad and William a Nilot—that is, they belong to different ethnic groups—William becomes a surrogate father to Mustafa. Layla, too, by falling in love with William, steps outside the bounds of her ethnic community and enters into a new “family” at the compound. Dena and Alex are the privileged outsiders, but the vulnerability to which the war exposes them means that they can no longer take their privileges for granted; they must rely on each other and on William, Layla, and Mustafa to survive. By bringing together this group of characters, I was trying to think beyond the limitations of the nation-state—a construct that’s very much grounded in shared ethnicity, religion, culture, identity. Utopian political possibilities often first exist in intimate relationships: a post-national, post-ethnic community first exists amongst a small group of intimates. Once that possibility is realized in the intimate sphere, in the sphere of friends or family, it perhaps becomes possible in the political sphere. This group of characters point toward that utopian possibility.

Early in the book, a burnt body is discovered. The body is unrecognizable, and they don’t know whether to bury it in the Christian Nilot section of the cemetery or the Muslim nomad section. Who was killed, by whom, why? It haunts the people at the NGO compound. The answers will affect their lives, yet the police have no real interest in the matter. As the characters’ thoughts return to the body, the tension rises. Is it also a metaphor for the whole situation in Saraaya?

The corpse is the first thing I wrote of GHOST SEASON, and for a long time I myself wasn’t sure what to make of it. Was I writing a murder mystery? Did I have to “resolve” the mystery of the burnt body? What does the corpse mean? These were all questions I struggled with, and yet from the beginning, I knew that the dead body was one of the key organizing images of the novel. The moment in which the characters hesitate over where to bury the corpse—in the Nilot or nomad cemetery—is important because ethnic and religious identity is central to the story, and to the story of Sudan and South Sudan generally. And yet ethnic and religious identities are often far more complex than we take them to be. Because the dead body is ashes when it’s discovered, the ethnic and religious markers that the characters—and the townspeople—take for granted are erased, are no longer visible on it. It becomes impossible to classify the body according to these markers. So the unclassifiable nature of the dead body points, in fact, to the complexity and fluidity of identity when we have nothing to go on other than bones and innards.

On another level, I think the image of the corpse is so central, for me personally, because it’s an image of the lifeless nation-state. I wrote this novel in the aftermath of the secession of South Sudan in 2011. The South Sudanese fought for decades for independence from Sudan because they were never treated as equals and were never going to be treated as equals within the larger nation-state of Sudan. The nation of Sudan, as the offshoot of colonialism, was already dead upon inception in 1956; it was a failed state because it was an unequal state, inheriting legacies of inequality and exploitation from the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium. And then, South Sudan seceded in 2011, and almost immediately collapsed into civil war, despite the sacrifice of millions of South Sudanese who fought, suffered, and died in the civil war against the north. The promise of the “nation-state” has yet to materialize in Sudan and South Sudan. So for me, the corpse is an image of the “dead state” of all nation-states, not just Sudan or South Sudan, but of course also nation-states such as the United States and all national powers that operate on principles of extraction, exploitation, and violence.

Finally, the dead body poses a question at the beginning of the novel: Who is the corpse? GHOST SEASON is preoccupied with the five characters around the corpse. By the end, I think (and hope!) the book gives an answer to the question Who is the corpse? Albeit indirectly.

Maslahat Al-Misāhah. Sudan. Khartoum 1976. Access granted by the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

As the political friction in Sudan rises, the distrust between the northern authorities and the southern rebels escalates, leaving the Nilotes in Saraaya sandwiched between them. Suddenly the NGO is drawn violently into the conflict. Was this inevitable?

I think it was. The NGO compound in which much of the action takes place is a kind of “bubble” in which the characters exist. They venture out, observe the war from it, but they are contained within it. Finally, the war spills into the compound, and it’s a key moment in which the safety of this “inside” bubble is burst. For Dena and Alex especially, who are the privileged ones, it’s the first time they truly experience themselves as vulnerable. The war is no longer an abstraction, something happening “out there,” to be filmed by Dena or mapped by Alex. It is a reality that leaves its scars on the body. And this experience transforms their understanding of themselves, of their place in Saraaya, and of their relationship to each other.

The novel is part thriller, part love story as William carefully develops a relationship with Layla, although it’s across the ethnic and religious divides. GHOST SEASON is really William’s story. Would you agree?

Yes, I think William is the pillar of the story. He is the translator figure: the one who is able to communicate across all divides, to hold all identities and differences within himself. Often these identities and differences exist in tension, but he’s the character who points to the possibility of openness and multiplicity.

Do you have another book underway? If so, would you tell us a little about it?

I’m working on a collection of stories and a novel. The novel is still very fresh, so all I’ll say is it’s set in the US.

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024