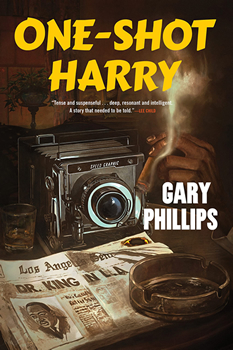

One-Shot Harry by Gary Phillips

By Tim O’Mara

By Tim O’Mara

As ONE-SHOT HARRY opens, it’s 1963 Los Angeles on the eve of a visit by Martin Luther King Jr.

Korean War vet turned crime photographer Harry Ingram looks to cover King’s Freedom Rally at LA’s lesser known Wrigley Field. A foxhole buddy from the war returns to town and then dies under mysterious circumstances. As he seeks answers in his friend’s death, Harry’s investigation will uncover larger schemes being played out by the hidden power brokers who run the city.

In this interview for The Big Thrill, author Gary Phillips shares insight into the inspiration for both the plot and his protagonist, plus puts together his dream panel for ThrillerFest.

Your protagonist, Harry Ingram, is a Korean War vet and crime photographer. How do those two characteristics affect how he views and navigates Los Angeles in the early ’60s?

It’s not giving too much away to note that Harry carries with him a guilt from an incident in the war. It’s also in the war where he essentially inherits the Speed Graphic camera from a correspondent who is killed in combat covering the squad Harry’s in. Interesting too that the Korean War ends in a stalemate, the north and south divided, yet all these lives lost, disrupted, and uprooted over what could have been settled at the conference table. These are factors rumbling in Harry’s psyche. He realizes he’s drawn to conflict, keeping two police scanners in his apartment, and when something hot comes over the airwaves, out he rushes to capture someone’s arrest or death. But he’s operating in a city that, while still segregated, is changing nonetheless. Harry has a car, theoretically he can go wherever he wants—yet he knows there are parts of the greater Los Angeles area where he’d best be wary.

Harry and a buddy of his, who lost his sight in the war, have what was back then called “shell shock.” These are all elements that come into play regarding Harry and his relationships to the other characters in the book.

What are the similarities and differences between being a crime photographer and a crime novelist?

On the surface, we both give you a portrait of the thief, the gambler, the short-cutter, the poor schmuck lying there with a knife in his forehead. Where we deviate is the crime novelist has to get below the surface of those frozen images presented in stark black and white to explore what events led up to the corpse in the vestibule, or that woman who has a black eye and is holding a handkerchief to her bloody nose near the body. What was her life up to that point and even afterward?

What is the significance of LA’s Thomas Guide?

Oh my. In those days before you kids had them Internets (a series of tubes as the late Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said) to access Google maps or even had Mapquest, there was this wire-bound, plasticene-covered rectangular guidebook. Its pages contained street maps, including freeways. You looked up the address and street you were looking for by municipality in the index and this gave you the coordinates to find the location on the correct page. You could then figure out from that which major streets or freeway to take, as it showed you off-ramps, to get where you were going. You kept that bad boy in the car ’cause you were going to get turned around. Harry Ingram knows the city pretty well, but even he’s not so smug as not to keep his well-used Thomas Guide with him.

ONE-SHOT HARRY is infused with jazz and blues. Do you listen to music while you write? For inspiration? Which musical artists do you believe were/are the best “storytellers”?

Funny enough, I keep the radio going when I write, tuned to either one of the NPR stations or the Pacifica one here in town, KPFK. News of the world, local talk programs, a music show called Morning Becomes Eclectic. All of it is a kind of white noise that somehow one part of my brain hears yet I can focus on writing. But for sure when it comes time to decompress, jazz and blues are what I listen to. Sometimes it’s online, or a CD, radio station KJAZ, or late at night in my sanctum sanctorum, to borrow the phrase from Dr. Strange, I’ll listen to the archived Ann the Raven show on KCSN. She’s had a blues show on the radio since the ’80s.

There’s too many artists to name as compelling storytellers, but John Lee Hooker, Sister Rosetta Tharp, Lightnin’ Hopkins, B.B. King, and Warren Zevon (not blues but still) always come to mind. Their lyrics and evocative song stylings work so well together.

Your work has been described as having a “political edge.” How can crime fiction (and photography) be used as such?

Mindful that my goal is to entertain and not preach, I try my best to blend in those elements of a socio-political nature. ONE-SHOT HARRY is set in 1963, so there’s no escaping depicting certain attitudes of that era; how a mostly white police force related, or not, to a Black citizenry, housing practices then, and so on. On top of that, here’s this man with a camera, an interloper, who because his job is to get the shot, finds himself in different parts of the sprawl of the Southland often on the scene when people are grieving or in shock. And yet he’s this cat snapping away.

You’ve been story editor on Snowfall for years now. How does telling stories on TV compare to, and differ from, telling them on paper?

It’s quite a charge to hear your words coming out of an actor’s mouth. That’s pretty sweet. Too, the writer’s room is such a charged process; ideas fly about fast and furious. Sometimes we go far down a path where we want to take our characters then two days later scrap all that. A lot falls by the wayside while other scenarios make it to the board and even make it into the script. Everybody gets a say, but there are times when the show runner has to make the final decision based on hours or days of input. In that way it’s so different than writing a novel since it’s just you and what you decide to put on the page. Though I will say while we work from an outline in TV and I also outline my novels, like in the room, I riff and change course and jettison parts of the novel’s outline as well as I write and re-write…and rewrite again.

If you could put together your dream panel for ThrillerFest—participants need not be living to be invited (why discriminate?)—who would be on the panel, why, and what would the topic be?

Wow. How cool would it be to have Hammett, Chester Himes, Dorothy B. Hughes, Ida Lupino, (queen of ’50s noir directors) and Sam Fuller on a panel? As to why—well, hell, they all influenced a whole bunch of us old timers as practitioners of the tough and terse. The topic? Hardboiled as Hell.

*****

Gary Phillips’ background includes being a community activist and labor organizer. He’s published various novels, comics, and short stories and edited several anthologies. Violent Spring, first published in 1994, was recently named one of the essential crime novels of Los Angeles. He’s been a staff writer on Snowfall, an FX show about crack and the CIA set in 1980s South Central where he grew up.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman - September 30, 2022

- Homeland Insecurity by J.L. Abramo - August 1, 2022

- Unruly Son by Neil S. Plakcy - May 31, 2022