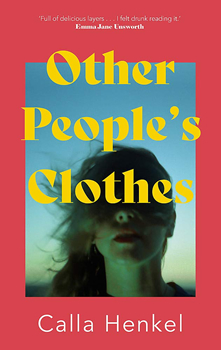

BookTrib Spotlight: Calla Henkel

In Glittering Berlin, Fiction and Reality Collide

“Start from the beginning,” she insisted and if I were allowed to smoke, I would have lit a cigarette. I was always good at telling stories and this one always felt like it belonged to someone else. [But] everyone knew why I was there. [We] were all anyone could talk about.”

You’d be talking, too.

The young woman speaking in Calla Henkel’s OTHER PEOPLE’S CLOTHES is Zoe Beech, an American art student who has fled to Berlin in 2008 for any number of reasons. She doesn’t know who she is, and she hates the school she’s in now, which revolves around toxic masculinity: “In the pit, the easiest way to dismiss a female’s work was by calling it domestic. Or decorative. The double Ds.” That’s not even mentioning the pornographic multigenerational mural of freshmen girls wrapped around the ceiling adjacent to the senior studios.

Mostly, though, Zoe fled because of the murder of her best friend, Ivy, her body found stabbed 14 times in a Florida sand dune next to a highway. The horror of the murder itself is bad enough; the guilt of having pushed Ivy to take the trip is even worse.

The Berlin art school—“a labyrinth of unheated, debris-littered hallways that reeked of turpentine”—isn’t much better than the one she escaped, and the city itself seems completely inhabited by cool people going to fabulous parties to which she is decidedly not invited—but at least she has Hailey. A conceptual artist filled with all the boldness Zoe lacks, it is Hailey who’s found them the wonderful apartment: a high-ceilinged prewar sublet belonging to a famous thriller author named Beatrice Becks, who is about to leave for an extended writing retreat.

Zoe is interested in Becks, but Hailey is obsessed with her—her fame, her books—obsessed by anyone living in the glare of the public spotlight, for that matter: Amanda Knox, Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan. And when she reads an interview stating that Becks’ work-in-progress has changed to become about two clueless 20-something American girls in Berlin, she becomes obsessed with what Becks is going to write about them. “We have to give her something to write about,” she says: “It can’t be about our depressing life… It will be a performance. We could build a real spectacle, [so] we control the narrative, so Beatrice writes our version.”

And they begin to build a story. Exceeding all their expectations, they turn the vast apartment into an after-hours, invitation-only club called—what else?—Beatrice. It’s filled with glitz and music, and as with any exclusive club, the more people get turned away, the more people want to come. The parties get bigger, louder, wilder, a whirlwind of excitement… but then they start spinning out of control. Who are those people lurking in the corner? What are those noises in the night? Why does it feel like someone’s spying on them? What does it mean that no one at that writer’s retreat has ever even seen Beatrice there?

And why is none of this enough for Hailey’s thirst for drama? The arc, she tells Zoe desperately, they need a better arc. “We need something to really pop…a love triangle or murder or incest.”

What comes next pops, all right. It is outlandish, unforgettable, horrific—and only the beginning of a tale that keeps unwinding. Filled with twists and turns, told with psychological richness, barbed social commentary, and a ton of wicked black humor, Calla Henkel’s novel becomes both a terrific thriller and an acute exploration of fame, friendship, identity, and the lengths we will go to fit in—and stand out.

Other people’s clothes. Other people’s lives. Other people’s crimes.

Whose story are they living—and how will it end?

Certain elements of the book echo the author’s own history. A writer, playwright, director, and artist, Henkel moved to Berlin as an art student, and currently owns a combination bar, performance space, and film studio there.

“Back in 2008,” she says, “I went on exchange to Berlin, and my best friend and I stumbled on a sublet from an iconic ex-pat author. We moved in, and with nothing else to do, devoured the author’s library and obsessed over her.”

Like Zoe, she felt like an outsider: “I was definitely an idiot. I think foreign exchange students are one of those ultimate forms of late capitalism, privileged kids who are expected to consume (food, language, culture) until they become. There is an absolute violence to it. I think maybe that’s another part of the reason Amanda Knox was so interesting for me. But yes, I felt like an idiot, and I was.

“But the idea to set that time period to fiction came years later, while thinking about the inky territory of the sublet and how it enables one to take over someone else’s life from the inside. I completely mutated our mundane reality. I was working with my real timeline. I went to art school, I moved to Berlin, I opened a bar, etc…but it is truly fiction. Most of my friends can’t even really recognize anyone in the book. And it was important to me to avoid rendering a caricature of the scene. That being said, there are plenty of real anecdotes and experiences baked in, and after years of running bars, and endless nights of listening to drunk people’s stories, I had a lot to pull from.”

That included her time in the New York art school, and the Berlin nightlife scene, both then and now: “I went to art school at the end of the lumberjack-bro era, and I didn’t realize how impacted I had been by that energy until I sat down to write the novel. There was a lot that we, the female students, just accepted as normal. The murals about girls on the wall is all true. So was the frat energy. There was of course brilliant work that got made—and a lot of insane parties—so it wasn’t all bad, but I do think there have been a lot of healthy strides away from this era in the past decade.”

As for the other: “I actually think the unofficial parties and weirder hybrid spaces are what make Berlin amazing. The best parties that I used to go to were at an art studio that turned into a club on weekends. I think the pandemic also brought the old scrappiness back, all the official club energy moved outside, and there were all these micro raves, and the parks were flooded with people dancing, and the door politics evaporated; anyone could join.”

Also resonant of her own history is Zoe’s journey of self-discovery. “Over the course of writing my novel,” she noted in an online essay, “I came out. I mean, I had already come out (unexpectedly) to my best friend while drunk at a wedding years prior. And I had since then occasionally dated women. But still I kept holding out from doing so fully, not certain of my queerness and selfishly frustrated that acknowledging my sexuality hadn’t magically solved my problems.

“I had wanted an explosion. Instead, I found that I was the same person, only with different baggage. In the process of writing the novel, I was able to hover above the chaos that lingered inside of me to untangle my hang-ups and then twist them back together in a different formation for the page….”

“I think there was something really powerful about being quiet and in my head,” she adds now, “and unpacking Zoe’s relationship to women and the language I had been denying myself.”

Twisted in a different formation as well was Zoe’s and Hailey’s determination to dictate their own story: “The book is definitely built with the same questions that show up in my art practice. I work collaboratively, and often through photography with ideas of performance and documentation, unpacking how one can control personal narrative through image. I think Hailey and Zoe’s practices are both linked to my own, and it was really energizing to allow them to grow in absurd ways which I would never allow myself.”

As for the choice of a thriller format: “I love thriller novels. My family is from Florida, and I grew up reading Carl Hiaasen. I also love Patricia Highsmith. The Talented Mr. Ripley is definitely burned into the DNA of my book. The characters of my novel all feed on aspiration, a want to become something, performing versions of themselves in a hall of mirrors, hoping to catch the truth.

“I think everyone should strap the engine of a thriller to the narrative of their lives.”

Her next novel will also be about art and murder, “a book about a girl who defects from the art world and moves to the mountains, only to end up bingeing murder podcasts and obsessing about her ex-boss who has mysteriously disappeared.”

In the meantime, though, OTHER PEOPLE’S CLOTHES is not only a sensational read—it’s due to become a sensation on the screen as well. In an eight-way auction, Mark Gordon Pictures bought the film and television rights, with Alexa Karolinski, the writer of the brilliant Berlin-based limited series Unorthodox, set to adapt. “I can’t want to see these girls come to life in all their dark, sparking intensity,” says Henkel.

After reading her book, you’ll feel the same.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024