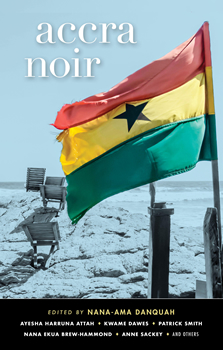

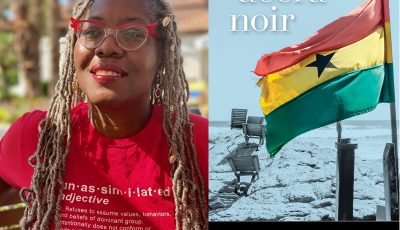

Africa Scene: Nana-Ama Danquah

The Paradox of Order and Chaos

Nana-Ama Danquah is an author, editor, freelance journalist, ghostwriter, public speaker, actress, and teacher. Her groundbreaking memoir, Willow Weep for Me: A Black Woman’s Journey Through Depression (W.W. Norton & Co.) was hailed by The Washington Post as “A vividly textured flower of a memoir, one of the finest to come along in years.”

A native of Ghana, Danquah is the editor of four anthologies: Becoming American: Personal Essays by First Generation Immigrant Women (Hyperion); Shaking the Tree: New Fiction and Memoir by Black Women (W.W. Norton & Co.); The Black Body (Seven Stories Press); and, the most recent, ACCRA NOIR (Akashic), as part of their popular noir series. She lives in Southern California.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Danquah talks more about the new anthology and her thoughts as to why African writing seems to be making its mark on the global literary stage.

African writing was in the spotlight last year, with the announcement of Tanzanian-born novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah as the 2021 Nobel laureate for literature, and South African Damon Galgut winning the Booker Prize. Would you agree that African literature continues to draw attention globally?

Every year, decade, and era has had its fair share of African writers who have reached great heights (insofar as the world of awards is concerned) with their work. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has been in the spotlight, winning awards. Teju Cole as well, and Helen Oyeyemi. If we want to reach further back, there has been Ben Okri, Wole Soyinka, Ama Ata Aidoo, Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee, Ngugi wa Thiong’o. I could go on. The African continent has continuously produced top-notch writers who have enjoyed acclaim in one form or another throughout the entire world.

Indeed, the history of accolades shows the weight and importance of African writing. You write in the introduction that Ghana became the first sub-Saharan, or ‘Black,’ nation to gain independence from colonialism, in 1957. How did independence influence the writing from Africa?

I believe that the creation of art—be it literature or visual art—has always been prominent in Africa. The access to outlets that were willing to publish what was being written was clearly limited during colonialism. That is why there was an explosion of African literature during the period of time when those African countries, one after the other, were winning their independence. Heinemann, for instance, began its African Writers Series imprint, and that made African writing accessible to the rest of the world.

Briefly, how did colonialism influence the development of Ghana, and what are the remnants, now, in Accra?

People have written entire books about the effects of colonialism on various nations, so I think it unwise to tackle any sort of direct answer to that. I do believe that the contributors to ACCRA NOIR, in their stories, do a wonderful job of describing the remnants of that colonialism—in the architecture, the street names, the names of certain neighborhoods, the English names of characters, and so on. The streets in Accra honor not only its own independence and the events that led up to it, but also the architects of independence in other nations throughout the world.

You write in your introduction that “Accra is a city that stands at the center of the world,” as a meeting point of East and West, a cultural crossroads. For those who have not visited Accra, how would you describe it in terms of being a microcosm of Ghana?

In most developing nations, people are drawn to the capital city because of educational and economic possibilities; citizens flock to any large metropolis in search of better employment opportunities and because they want to live in “the big city.” Ghana is no different. There are just more opportunities available in Accra than in the villages. So people come to Accra from all over the country, bringing with them their foods, languages, cultural, and religious beliefs. In this way, Accra is a microcosm of Ghana. It is a mini-Ghana.

And what of the city itself? The city we see in the stories? The passion, the color, the action and energy?

Accra has similarities to any other major city—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, London, Paris. The hustle. The bustle. There is thick traffic. There are plenty of taxis; the vehicles used for taxis are usually painted in two-toned colors (different combinations, so I can’t say blue/yellow or white/black). There are Land Rovers, BMWs, Mercedes Benzes, as well as Peugeots, Toyotas, and other vehicle makes and models. You will just as quickly spot a brand-new vehicle that has just been released by the automobile maker as you will a jalopy that is spewing smoke from its exhaust. At the traffic lights, hawkers will often walk up to cars selling all manner of things, from chewing gum to newspapers to shoes and purses, Q-tips, and food. The women hawkers have their merchandise on huge aluminium platters which they carry atop their heads.

The markets are filled with food sellers, some seated on low wooden benches, several silver platters in front of them, their merchandise—peppers or onions or tomatoes or smoked fish or giant land snails in their shells—displayed in front of them. Some of the sellers have stands, the height of a standard table, on which they place their wares. The markets are often a maze of activity. You turn a corner and you are no longer in the portion where food is sold but in the area for cloth, or shea butter, or household goods such as buckets and plastic tubs, or silverware and plates. Between the colorful food, the colorful wrappers that the women—the ones selling as well as many of the ones buying—wear, the smell of the food, and the noise of price haggling and negotiations, the markets are always a feast for the senses.

To talk more of crime, West African cities are said to be some of the most unsafe in the world in the 21st century. The stories in ACCRA NOIR cover rape to murder, from the intimacy of the bedroom to the hustle and bustle of streets and alleyways of the city. Rough justice can easily play out, as you say, “in the shadow of the Supreme Court and parliament buildings,” showing us the paradox of order and chaos. This paradox seems typical—poverty and desperation juxtaposed against wealth and the establishment. Is this chasm between rich and poor, tradition and modernity, a root cause of crime there?

I don’t believe crime has a single root cause. Some people commit crimes out of desperation; some people out of curiosity; and some out of boredom, and for other reasons. That is the beauty of the stories in ACCRA NOIR: they explore the motivations for the crimes that are committed. And those motivations range from poverty to jealousy to insecurity, to power, and on and on.

Crime has always, to some extent, existed in all societies in the world. That said, I do believe that income inequality, as we are currently seeing even in many so-called developed nations as well, does serve as something of a prelude to crime as well as to revolution. I think part of the reason the chasm to which you refer even exists is that so many societies exist in binaries, so it can often be challenging to find a middle ground, especially when the distance between two realities grows too wide.

Getting to the writing, you say in the introduction that Accra is “a city of storytellers.” The people of Ghana “live and love in parables and aphorisms and proverbs.” Apart from the crime aspect—corrupt cops, crooked politicians, thwarted lovers, disillusioned citizens in despair, all represented—I loved the language of the book, the turns of phrase, the cultural references that come through.

I labeled Accra a city of storytellers because everything one encounters is an invitation to story—there are aphorisms, symbols, street names everywhere that are all just stories waiting to be told. There is a story even in an individual’s name because we have names that can indicate whether someone is the first or second of a twin birth, names that indicate whether someone is the single birth that followed a twin birth. Children are not formally named until the eighth day after birth, so our “day names” correspond with the days of the week. Kofi, for instance, is a baby boy born on Friday. Ama is a baby girl born on Saturday. Thus, one might assume, since my name is Nana-Ama, that I was born on Saturday, but really I was born on Wednesday and would ordinarily be given the day name Akua, had I not been named after an elder whose day name was Ama, hence the name Nana preceding Ama.

Everyone in Accra has a story to tell, a story prompted by their name or facial tribal mark, or cloth they are wearing, or the symbols on that cloth or on their jewelry or home décor. This shows up beautifully in many of the stories.

How did you go about commissioning the stories? Many of the writers are well known beyond Accra. You’ve put together a wonderful collection of erudite minds.

I commissioned stories from authors I thought would bring a unique angle and voice. From there, the authors chose a neighborhood in which to set their story. They chose the plot, characters and, of course, crimes. I had no say in that at all. I only made sure that we didn’t have ten stories with the same crime and motive—but, given the contributors and their different backgrounds and experiences, there was no chance of that.

Kwame Dawes, who is based in the US, is a prolific, award-winning poet and fiction writer. Nana Ekua Brew Hammond, who is US-based, and Ayesha Harruna Attah, who is based in Senegal, are both award-winning novelists. Gbontwi Anyetei, who is based in Ghana, is a novelist as well. Billie McTernan, currently based in Ghana, is a highly respected journalist in Europe, where she worked for many years, and in Ghana. Patrick Smith is the editor-in-chief of The Africa Report and Africa Confidential magazines and is based in Paris. Though some of the writers are being published for the first time in ACCRA NOIR, they are high achievers in their own right: Anna Bossman is Ghana’s former commissioner on human rights and administrative justice and the nation’s current ambassador to France. Anne Sackey is a highly sought-after marketing expert; Adjoa Twum, who is based in South Africa, is a public health manager; Eibhlín Ní Chléirigh, who is based in Ghana, has worked extensively in design and communications. Ernest Kwame Nkrumah Addo, who is Ghana-based, is studying in South Africa for his PhD but has previously taught at the university level and worked for the presidency as a speechwriter.

What was the driving force behind splitting the collection into four parts, and what does each part signify?

It was merely organizational. I labeled each section with an aphorism that is commonly seen or heard in Accra: Sea Never Dry; All Die Be Die; Heaven Gate, No Bribe; and One Day for Master, which is one of my favorites. It’s a shortened version of “Every day for thiefman, one day for master.” In that section, the stories are really about betrayal and comeuppance. In Heaven Gate, No Bribe, the stories are about crimes committed in the name of financial greed. All Die Be Die means that regardless of the motivations or reasons, death is still just that—death. The stories in that section overlap love, jealousy, and murder. In the final section, Sea Never Dry, I included stories about situations that are, sadly, not uncommon—such as a young woman needing to free herself of an older, ailing husband who is not dying quickly enough; a young boy who, because of the death of a beloved parent, finds himself on the streets only to be used and discarded like rubbish; and the dangers and complexities of both transactional romantic relationships and mob justice.

I have to add that the organization of these stories into these sections was done after the stories were all submitted; none of the authors wrote their story in order to fit into a certain section.

Here is an unfair question. Do you have a favorite story? Or a few?

Hahaha. That’s like asking a parent to choose their favorite kid. I love all the stories, and they take turns being my favorite. Each one has its own personality and daring. I am absolutely gutted by “Fantasia in Fans and Flat Screens” by Kofi Blankson Ocansey because he worked so very hard on that story but passed away before the book was published, so that one has a special place in my heart.

And of course, what drives your own love of noir fiction?

I love good literature. I am not a fan of any particular genre of literature. I love any type of well-written literature that explores the human condition. Noir tends to explore the darker side of the human condition, and that’s what draws me to it.

When I realized that, at the time, Akashic’s popular Noir Series, in which each book focuses on a particular city, did not have any books focusing on any African cities, I pitched Accra because I thought it would lend itself well to the genre. Thankfully, the publisher agreed with me, and thankfully there are now numerous African cities represented in the series.

For readers who don’t know Africa, I would say this is a must-read, particularly for noir readers wanting to explore a thriving, throbbing African city. I’m sure you agree!

I believe people should read the collection because the stories are well-written and interesting. Some of them offer new twists on old noir tropes. Others are utterly original takes on the genre. And then, too, is the fact that these stories are all taking place in Accra, a city that is entirely unique, its own place, unlike any other African city.

Lastly, how has ACCRA NOIR been received in Ghana?

In Ghana, the events that have been put on were all filled to capacity, and I have received nothing but wonderful and positive response from friends and relations of mine as well as from the contributors who have shared with me the comments and response they’ve received. It has indeed been well received.

ACCRA NOIR is a collection that will enthrall and keep the reader turning the pages, especially those who have a desire to explore new places, perhaps a little exotic. I finished your book salivating for a trip to Accra, a city I’ve only ever visited in fiction. Thank you for putting together such an intriguing collection.

- Africa Scene: Nana-Ama Danquah - December 31, 2021

- Africa Scene: Sifiso Mzobe - April 30, 2021

- Africa Scene: Natalie Conyer - December 18, 2020