Africa Scene: Natalie Conyer

Conyer Returns to Roots for Debut

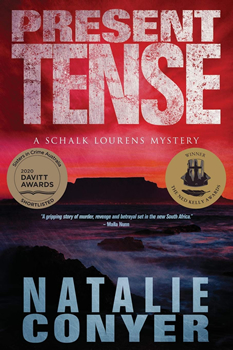

In Natalie Conyer’s novel debut, PRESENT TENSE—the first book in the Schalk Lourens Mystery series—veteran cop Schalk Lourens wants a quiet life. Like the rest of South Africa, he’s trying to put the past behind him. But the past has a way of hanging on, and when Schalk’s old boss, retired police captain Piet Pieterse is brutally murdered, Schalk must confront old demons. Pieterse has been “necklaced”—a tyre placed over his head, doused in petrol, and set alight. Who would target Pieterse this way, and why now, 25 years after apartheid ended?

Meanwhile, it’s an election year, and people are pinning their hopes on charismatic ANC candidate Gideon Radebe. But there’s opposition, and this volatile country is on a knife edge. A wrong move could generate a catastrophe.

Captain Schalk Lourens, drawn into a world he no longer knows, where shadowy forces call the shots, treads a path between the new regime and the old, the personal and the professional, justice and revenge.

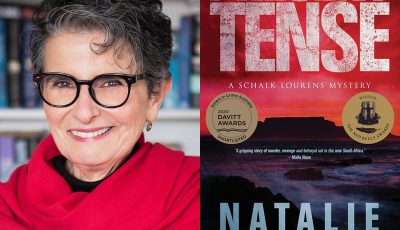

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Conyer shares insight into her career, the inspiration for PRESENT TENSE, and what readers can look forward to from her next.

Congratulations on your Ned Kelly Award for the best debut crime novel in Australia in 2020. PRESENT TENSE was also shortlisted for a women’s crime writing award, the Davitt Awards, in two sections. You must be thrilled!

Yes, the book is doing well. Aussie rural noir is still flavor of the month here, but I think people respond to a strong sense of place, which I hoped to create in PRESENT TENSE.

Although South African-born, you’ve lived in Australia for many years. For what reasons did you choose to write a novel set in South?

I was born and grew up in Cape Town. I left South Africa, mainly to escape apartheid, in 1972 just after I finished university (I’m a very late onset writer). I chose Australia because my boyfriend at the time was here.

Once in Sydney, I wanted nothing to do with South Africa. I wouldn’t read anything from it or about it; I didn’t follow South African news (other than the 1994 first democratic elections and Nelson Mandela becoming President), and I avoided newly arrived South Africans.

Then, in 2011, friends suggested we “see where you come from,” and I returned to Cape Town. It had changed completely, of course, but I realized I was viscerally connected to it. I needed to come to terms with that, and to think about it.

I’ve always been interested in crime fiction and find it a good way of examining a society at a particular point in time. Also, I wanted to write. So I chucked in my corporate job and enrolled first in an MA and then a DCA (Doctor of Creative Arts), researching the topic Crime Fiction in Post Apartheid South Africa. PRESENT TENSE formed the creative component of the doctoral thesis.

I wrote the book to understand what was happening in the new South Africa and how people were adapting to it.

Cape Dutch farmhouse in Franschhoek, such as owned by Piet Pieterse, similar to the one where he is murdered.

To put it in a nutshell, PRESENT TENSE is a hardboiled police procedural about an ordinary policeman in the “new” South Africa. Are you drawn to the hardboiled style?

I do like hardboiled crime fiction but not exclusively. I’ve been reading crime fiction for as long as I can remember and have many favorite writers, going back to the “golden age.” (For example, Dorothy Sayers’s Gaudy Night is a terrific read.) Hammett and Chandler are worth rereading, as are Maj Sjöwahl and Per Wahlöö, early Scandi writers.

Later favorites include Ian Rankin, Val McDermid, Ann Cleeves, Tana French, Don Winslow, Le Carré, Robert Harris, and Mick Herron.

In Australia, Peter Temple, the late South African-born writer, is just magnificent. His novel Truth won Australia’s major literary award, the Miles Franklin. His Broken Shore is my favorite. I like Adrian McKinty’s Sean Duffy series; Dervla McTiernan’s novels…I could go on forever.

As research for this book, I read as many South African crime writers as I could and enjoyed Mike Nicol, Margie Orford, and Deon Meyer in particular. Also Lauren Beukes’s Zoo City. And, if you haven’t come across it yet, there’s an Irish novel about truth commissions you shouldn’t miss: The Truth Commissioner by David Park.

To get to your protagonist, with Schalk Lourens’s particular literary history as the main character in the Herman Charles Bosman novels, what were your reasons to choose this name for your cop?

My character, Schalk Lourens, is an ordinary man, damaged by his past and trying to adjust to the present. But as I thought about him, I realized nobody in South Africa is “ordinary.” There’s a tangle of cultural and racial history behind us all. I felt I needed to complicate him. Using the name “Schalk Lourens” allowed me access to these complications.

Schalk Lourens is half-English and half-Afrikaans, and his identity thus spans the two White “tribes” that have been at odds with each other, and sometimes at war, for centuries. This led me to think about Herman Charles Bosman, who was also half-Afrikaans. Though Bosman himself was complex and cosmopolitan, his Schalk Lourens is presented as monocultural: a laconic, simple Boer farmer who observes—and reveals—the fallibilities of people round him. The stories themselves, however, are ironic and humanist, and this adds another layer of complexity.

Another reason for choosing the name was its link to the past. Bosman’s “Oom Schalk” stories are set in the time of the Boer War (1899–1902) and I wanted to show how the past has affected the present. In South Africa, sins of the past have not been expunged, and so the plot of PRESENT TENSE centers on past crimes surfacing in the present.

The foreshadowing around the past catching up keeps up the tension. Clearly Piet Pieterse, the victim murdered in the first pages, and Schalk have “history,” which indeed underpins the novel. What are Schalk’s particular fears, and what drives him?

Oppressive regimes damage not only the oppressed, but also the oppressors. As a young policeman in the 1980s in South Africa, Schalk was part of the oppressive regime of apartheid, and he did things then he is ashamed of. He’s haunted by what he did and is trying to make up for it by seeing that justice is done in the present. Yet his past still has a hold on him. He is emotionally stunted and doesn’t know who or what to trust.

Piet Pieterse, a remnant from that era, former cop with apartheid’s Bureau of State Security, clearly has a brutal and vicious past. Was his a particular character you wanted to explore?

Pieterse is a character that embraces the regime. I say in the book that Pieterse is a Dutch Reformed Afrikaner who truly believes in the master race. I wanted to explore his effect on Schalk in both the past and the present.

Until I was 17 my family lived in Bellville, a predominantly Afrikaans suburb, and I’m satisfied Pieterse isn’t an exaggeration. He’s an agglomeration of people I met there and later.

Could you tell us a little of the significance of the horrific “necklacing,” particularly as used to murder Piet Pieterse at the start of the novel?

Necklacing is a throwback to apartheid, an execution generally reserved for collaborators. It’s a particularly gruesome form of mob justice. During apartheid it was used by Black South Africans to punish those thought to have collaborated with the government. Used in PRESENT TENSE, it immediately brings apartheid past into the present day.

You include a hard look at the kind of interrogation and torture that went on with the special forces at the time. What was it that interested you about this?

I felt even a sliver of what happened needed telling. I wrote PRESENT TENSE with Australians in mind, people who didn’t know South Africa geographically, culturally, and historically. I was writing from the outside for the outside (I only saw this later), and so had to explain, and demonstrate, more of what went on than someone writing from South Africa for South Africans.

Incidentally, I read many Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) transcripts and was struck by the stupidity and banality of some of the cruellest undertakings of the apartheid regime.

For those who don’t know, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1995-2002) was a series of hearings predicated on a process of bearing witness or confessing to crimes committed during apartheid, leading to forgiveness for the criminal and sometimes judicial amnesty. Did you set out specifically to include comment on the TRC?

I included it because it is still alive in the country’s consciousness and because it is pertinent to the plot. One character’s records, their preparation for the long-ago TRC hearings, enables Schalk to make a breakthrough in finding out who murdered Pieterse, and why.

In PRESENT TENSE it’s clear that people in South Africa believe the TRC didn’t go far enough, and that in some cases unrepentant war criminals escaped justice.

Another primary character is that of Gideon Radebe, a prominent ANC politician implicated in Pieterse’s murder. It becomes clear that the two, Radebe and Pieterse, were respectively the interrogated and the interrogator in the past. Which is more prominent for you, politics or revenge, or a little of both?

Both. In South Africa, politics and justice and revenge are inextricably linked. I didn’t start with an abstract theme—I started with people and their pasts and what they did in the present and why. Jacob Zuma was still in power then, as President, corruption was rife, and the general mood at that time (2014/5–2017) seemed to be one of profound disappointment that the hopes of the “Rainbow Nation” weren’t being realized after the first democratic elections of 1994.

I didn’t set out to take any particular point of view on politics or justice, I just to set out what I saw and heard, especially from older White people who seemed to me to be to some extent rudderless in the new South Africa.

Getting to Schalk’s personal life then, he is clearly in conflict around his depressed wife, Elsa, when femme fatale Miri Pieterse enters the story early.

Miri was great fun to write. And poor old Schalk didn’t have a chance. Apartheid also damaged the oppressors, and I think Schalk has been emotionally stunted by his past. So he has no weapons against Miri. Also, as we say in Australia, he’s a bloke …

And as we get to know Schalk better, as a man, politics and revenge aside, there’s an unexpected twist as he suffers a personal loss, and the investigation turns on its head. What sort of “cops” does Schalk work with as he unravels the mystery?

The cops who work with Schalk are all colors and cultures—they’re Xhosa, mixed race, Indian, Jewish … that’s a reflection of the new South Africa. I worry sometimes that I produced a cliché group of rainbow characters but when I wrote them they were alive to me. Schalk gets on with them because he trusts (most of) them and because they are appealing people.

On the other hand, Schalk isn’t free of racist and sexist attitudes, and this has colored his perception of his boss, Sisi Zangwa, and affects his relationship with his colleague Winnie Mbotho. I guess this too is a reflection of the new South Africa—that the racist past is still alive and kicking.

How did you manage, working in Australia, to get the details so accurate?

I’d been away from South Africa, in every sense of the word, for nearly 40 years, so I had a lot to catch up on. I read everything I could get my hands on, including as much crime fiction as I could find. I read TRC transcripts, academic articles and books, and nonfiction accounts of life in South Africa. I subscribed to newsfeeds. I watched as many South African films and TV shows as possible.

Between 2013 and 2016 I visited Cape Town four times, for a month at a time. I made these visits coincide with the Open Book Festival, which helped me to feel the pulse of the place. I visited every site mentioned in the book.

I was also lucky in that an old school friend of mine had been a policeman during and after apartheid. He was kind enough to spend hours telling me about his experiences. He also gave me a contact at Cape Town Central Police Station, and I spent time there, learning how things worked and talking to the police.

With your success with Schalk and his precinct, what’s next for you?

I’m not done with Schalk Lourens yet, but I’ve just started on a completely different book with completely different characters, set in Sydney. And having fun with that!

- Africa Scene: Nana-Ama Danquah - December 31, 2021

- Africa Scene: Sifiso Mzobe - April 30, 2021

- Africa Scene: Natalie Conyer - December 18, 2020