An Old-Fashioned Detective Story—With a Twist

Bryony Rheam is a Zimbabwean who lives in Bulawayo. Her debut novel This September Sun was named Best First Book in the Zimbabwe Book Publishers Association Awards and went to #1 on the UK Kindle chart. She was one of the five Africans chosen for a Morland scholarship in 2018.

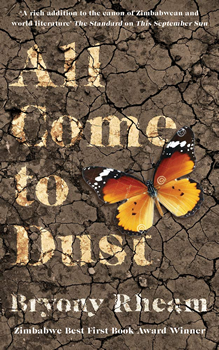

Rheam’s new book, ALL COME TO DUST, was chosen as one of ten top African thrillers in Publishers Weekly, who described it as a “stunning crime debut.” Paula Hawkins (author of The Girl on the Train) said it was “an intriguing, twisting murder mystery, a witty combination of old-fashioned detective story and keenly-observed portrait of life in suburban Bulawayo,” and that Chief Inspector Edmund Dube was “a fictional detective as memorable as Hercule Poirot.”

In the story, Marcia Pullman is discovered dead in her Bulawayo home with a letter opener sticking out of her chest, but there’s not enough blood, and it’s obvious that she had been dead before she was stabbed. Edmund goes to the scene, having to wheedle a lift from Craig Martin, who is at the police station arguing a speeding fine. The pathologist, a friend of Marcia’s husband, says she died of natural causes, and the senior officers at the police station seem intent on thwarting Edmund’s efforts to get to the bottom of the case.

Superficially, the book seems to follow the tropes of the detective story genre, but soon we see that it’s nothing like that. The rich characterizations and subtle surprises remind one more of P.D. James than Agatha Christie.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Rheam shares further insight into her latest release and teases what she is working on next.

Although your first book, This September Sun, also involves a murder, ALL COME TO DUST is more of a murder mystery. Initially, the story seems to follow the framework of a typical detective story—the smart detective who is committed to the solution of the crime against the odds, the cast of suspects, the unreliable witnesses. It even has the final gathering of the suspects where everything is to be revealed. But you turn everything on its head. Was that always your plan, or did the context drive you in that direction?

I am a great Agatha Christie fan and always wanted to write a crime novel. Like Christie, I am not a great fan of a lot of violence; to me, unravelling the mystery is the most important thing. However, the classic Agatha Christie-type plot belongs very much to a time and a place, and it was obvious that it would not work in Zimbabwe, despite our little English eccentricities that have survived 40 years after Independence!

Many of the characters have some link to a type of crime writer: Craig, for example, reads an author called DP Radley (a fictional author) who chases fast cars and is surrounded by beautiful women; Mrs. Whitstable reads Inspector Morse; Edmund reads The Saint. Yet none of these detectives seem to fit the location; they all seem to fall short in some way.

I suppose this is a reflection of the fact that I couldn’t use that same model of the detective story in the context of Bulawayo. The police are very unhelpful in Zimbabwe, and there is little in the way of forensic investigation, so I couldn’t rely on bringing certain information in in the same way. As I was writing, I became increasingly aware of the fact that the novel was not going to fit a certain model, and so I decided to undermine it instead.

Chief Inspector Edmund Dube is an intriguing character. He’s smart and committed to solving the crime, but his backstory suggests that he has many deep issues of his own. We follow his childhood in Rhodesia as the son of a live-in maid whose apparently kindly white employers help him go to a good school and even with his homework every afternoon. How did you conceive him and his role in the novel?

The Zimbabwean police are not well-known for being either efficient or useful. During the Mugabe days, they were synonymous with corruption. I thought that there must be someone in the force who wanted to do a good job, someone who signed up with good intentions. That’s where Edmund came in.

The classic detective novel focuses on the crime at hand: who did it and why. There is not much detail about the investigator’s life. More recent crime novelists often present the investigator/police officer as a lonely person, someone who has given their life to solving crimes as an escape from the chaos of a dysfunctional family life, an unhappy marriage, or an inability to connect to others on a social level. In some ways, Edmund falls into this category as his marriage is not a happy one. However, he is also isolated at work; he is not taken seriously and is constantly put down. This forces him to go off on his own and work independently of the police force.

I am always drawn to the idea of an outsider. Edmund has never fitted in: he was one of a small group of Black children who were let in to formerly white-only government schools in 1979. This was a very difficult time in the country’s history as it began to transition to majority rule. Edmund’s mother’s employers believe they are doing the right thing for Edmund by sending him there but are unaware of the challenges he faces. Later on in his life, Edmund once again feels he does not belong when he joins the police force and is forced to take part in activities that he does not agree with.

Edmund is intelligent and sensitive. He wants to do right in a country where everyone is very obviously doing wrong. He craves order and structure, hoping to put the world right by typing up traffic offences and making sure forms are completed properly, yet outside is chaos and corruption. There is no room for people like him. It was very important for me to develop his backstory and show how he came to be the sort of person he is. I liked the idea that he was solving a crime, and yet was also part of an unsolved mystery.

Marcia Pullman is the victim, but she and her husband are most unpleasant characters. Marcia dies in the first chapter, yet much of the book is about her and her impact on the people around her. By the end, we feel we know her well. Was it hard to build her character only through the eyes of the people who knew her?

I suppose in some ways, I was unfair with Marcia, as, apart from the very beginning of the book, I don’t show her point of view. Everything the reader learns of her is through other people. However, I feel she is more symbolic than anything else. There is a new type of corruption in Zimbabwe which in some ways is quite difficult to explain. For years, people have pointed at the government as the main source of corruption, the implication being that anyone else is not corrupt. I feel many white people in particular are like this. People fail to see how they themselves are drawn into the web of corruption. If they do acknowledge it, it is with the sense of “well, everyone else is doing it,” or “how else are we supposed to survive?”

Perhaps ironically, there is no racism in this new type of corruption: Nigel Pullman teams up with the police; Marcia buys valuable antiques off old people (who would be mainly white) and gives them nothing for them.

I based Marcia on someone I met who did this very thing. Back in 2000, when many people were leaving the country due to the farm invasions, she would buy up lots of valuable antiques and ship them to the UK. Many people had beautiful furniture that had been in their families for generations, but they did not really know what they were worth, tending to view them as old rather than antique. The same thing happened with old cars. You used to see lots of Morris Minors around, for example, typically driven by old ladies who had had them for years and years. Then buyers came from places like South Africa and bought them for a song. It was criminal.

Edmund identifies a cast of suspects: Marcia’s husband; the Pullmans’ maid and gardener; the peculiar neighbor; Janet Peters, who was bullied by her, and Janet’s invalid mother; a mysterious woman interested in her old records; and Craig Martin, who has threatened her. Each seems, in a way, to illustrate a different aspect of modern life in Bulawayo. Was that part of your plan for the novel?

Yes, it was. As well as writing a crime novel, I also wished to explore modern-day Zimbabwean society. We have all become increasingly isolated and lonely. This is due to politics and also the dire economic situation. There are those, like Marcia Pullman, who look after themselves at the expense of others, and there are those, like Dorcas, the maid, and like Janet Peters, who cannot stand up for themselves.

Craig is a handyman with poor business skills and low self-esteem. Edmund dragoons him to help with the investigation—staking out suspects, driving him around. Despite their wide differences, they seem to have features in common both in their adult lives and in their childhood pasts. Is this a yin and yang situation?

Craig and Edmund have much in common. They both had a traumatic event happen in their childhoods, and they are both essentially quite lonely characters, unable to connect to others. However, Edmund is definitely much more organized and focused than Craig, who really is very lost. Somewhere along the line, they help each other. When Edmund asks Craig to do some investigating for him, it gives his life a sense of purpose, and he, in turn, can be of more practical help to Edmund.

Much of the story takes place in a historically white suburb near where the Pullmans live. Several of the inhabitants are hard up after the runaway inflation, but those that have access to hard currency—in one way or another—are doing much better. Did you set out to explore the effects of this modern dichotomy in the country?

Yes, definitely. Life in Zimbabwe has been very difficult over the last twenty years. Hyper inflation wiped out life savings and pensions for many people. The transition to the US dollar was very clumsily done as well, and many people lost money that way, too. Sometimes it feels that almost everyone is doing something dodgy in order to earn US dollars! There is very little appeal in doing a conventional job as the salaries are so low. I think the older generation have been very badly hit. They struggle to survive on ridiculously small pensions, and really battle to understand the value of the currency as there is the official government rate of exchange and then the black market rate, which varies considerably. The divide between the haves and the have nots is widening considerably.

Would you tell us something about what you are working on now?

I have finished my third novel, The Dying of The Light, and it is at the editing stage. It is set in Bulawayo in the late 1930s and is told from the perspective of a house servant who works for a wealthy lawyer and his wife. I have started a book for young adults called Going Up. It is set in modern-day Bulawayo and concerns a young man who has gotten into drinking and drugs. His wealthy grandfather gives him an ultimatum to get himself sorted out and hands him the responsibility of evicting vendors from an old department store that he owns and wishes to knock down. However, the young man soon begins to develop other plans for the building and sets out to restore it to its former glory.

Just lately, I have been thinking of another crime novel, and may even bring Edmund Dube back, this time as a private investigator. I think the crime genre is a perfect one in which to explore the decay at the heart of Zimbabwean society.