Up Close: Anthony Horowitz

Murder at a Literary Festival

Literary festivals are one of the joys of being an author and a reader. People gather in cities of every shape and size where readers mingle with their literary heroes and writers have the opportunity for camaraderie with others who participate in this mostly solitary career. Guaranteed there’s been a literary or book festival near you.

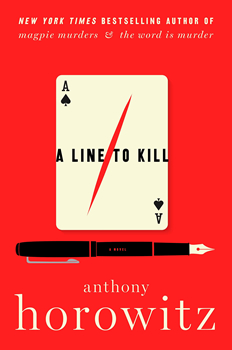

It seems fitting then that the new book in Anthony Horowitz’s Hawthorne and Horowitz series—A LINE TO KILL—brings his book-world self and former-detective Daniel Hawthorne to a literary festival on the island of Alderney, where the citizens cheerfully declare, “There’s never been a murder on the island.” Yet the suspects are plentiful.

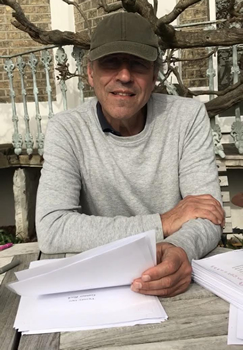

Even more fitting, we interviewed Horowitz while he was at a literary festival in Appledore, a village nestled along the Bristol Channel in England. He was about to be joined by about 20 other authors under a marquee that overlooks a picturesque bay and the little village that inspired the location for Moonflower Murders. After being cooped up during the pandemic, he was “happy to be able to resume a ‘new normal’ after so long.”

Similarly, Alderney is a real place. A small island only three miles long at the northernmost point of the Channel Islands, Horowitz had been there three years ago for a literary festival. “There really has never been a murder on Alderney,” he says, referring to the line in his book the residents of his fictional Alderney repeat.

Taken with the town’s charm, he wandered around, taking pictures and making notes. “I try to write in situ if I can,” he says. “I couldn’t make it back there at the time I was writing the book—just before the pandemic—but I do like to visit the locations I use.”

The island’s rich history provides both atmosphere and motive. “It had been occupied during the war, so there are bunkers and bulkheads and other things left behind,” Horowitz says.

The residents are a community in conflict, wrestling with striding into a twenty-first century future versus the desire to remain an unspoiled sanctuary. This tension creates a rich setting for a grizzly murder.

Several of the issues the island faces in the book mirror real-world events in the life on the island. “The conflict around the power line is real,” Horowitz says. “The digging up of war graves, the damage to the environment, are all real concerns the island is facing.”

Construction of the FAB—France-Alderney-Britain power line (changed to NAB—Normandy-Alderney-Britain—in the novel) is proposed to begin construction this year.

As in his two previous books in this series, The Word is Murder and The Sentence is Death, Horowitz has placed himself within the book as its storyteller. In A LINE TO KILL, we travel with fictional “Anthony” to a literary festival on Alderney. It’s a behind-the-scenes view of what it’s like to be invited to a book festival.

Horowitz’s self-insertion also adds another dimension to the narration of the story as he also behaves as a foil to the book’s hero, Daniel Hawthorn. Somehow, Anthony manages to make Hawthorne prickly—and yet the reader is drawn to him; we root for him.

The Anthony in the books has a love-hate relationship with Hawthorne. That the reader is charmed by Hawthorne makes the exasperation Anthony feels all the more humorous.

“Humor, warmth, and lightness of touch are what I’m trying to do,” Horowitz says.

The humor behind Anthony’s complaints comes through as a grudging affection for Hawthorne, earned in part due to Hawthorne’s quest to gain justice for all victims no matter how deserving they might have been. And the victim in A LINE TO KILL is quite deserving.

The suspect list includes a variety of authors from a variety of genres—children, cookbook, spiritual, poetry, and mystery—not to mention their partners and assistants, as well as the hosts and organizers of the festival. It’s a large cast and in lesser hands could feel unwieldy and confusing, but with a deft hand, Horowitz crafts each character into a unique person.

Developing his characters is one of the first steps Horowitz takes in writing his mysteries. It’s one of the ways he ensures each cast member is someone unique to him, too.

Horowitz celebrates the publication of Moonflower Murders—Book 2 of his Hawthorne and Horowitz series.

“I know all those people,” he says. “It’s a little easier in this book because each has a label—the cook, the children’s author, the poet—they’re neatly pigeonholed. But I do know these characters. The cook, for example, I know that person. I met him some years ago. The poet, I know her, too. Now that is to say, I don’t steal people body and soul, but there are mannerisms or traits that will strike me, and I’ll incorporate them into a character.”

Horowitz then weaves those characters and their stories into an engrossing whodunit. “I start writing my murder mysteries with the victim,” he says. “I start it with the murder. You don’t kill someone for a small reason. You kill someone for a big reason, and I try to come up with an interesting reason, an unexpected reason.”

What makes this book fun is that everyone has an interesting reason for murder. The characters carry their grudges, lies, heartbreak, and betrayal along with them to an uncomfortable cocktail party where all are delightfully convincing in their loathing for the victim. Clues are tucked into the dialogue and so cleverly disguised that even I, who was raised on Agatha Christie, ended up kicking myself for missing them. That “ah-ha” moment is deliciously satisfying.

Part of the joy of reading a mystery is to feel like we have a shot at solving it before the hero. In order for that to happen, the mysteries have to be set in a world we can relate to. The motives have to make enough sense to lull us into a false sense of knowing what’s coming. We guess where the plot is heading, so we end up missing the subtle clues pointing us to our murderer.

Horowitz doesn’t disappoint. There are red herrings, twists, turns, and false leads—and yet the conclusion doesn’t come out of nowhere.

“My mysteries reflect a world in which everything makes sense,” he says. “My mysteries at the end have to make sense.”

Which makes those endings all the more gratifying.

Horowitz says he has plans for maybe nine or ten more Hawthorne and Horowitz books.

“My original idea was to have titles with a literary flavor to them,” he says, but admits this will get harder as he goes along.

Not that it’s going to slow him down. As we spoke, he was already playing with some character ideas for his next book.

We can’t wait to read it.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: PASSIONS IN DEATH by J.D. Robb - October 26, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: DEVILS ISLAND by Midge Raymond and John Yunker - October 26, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: MURDER AT VINLAND, A GILDED NEWPORT MYSTERY by Alyssa Maxwell - October 26, 2024