Up Close: John Farrow

Visit to “Lady Jail” Inspires Thriller

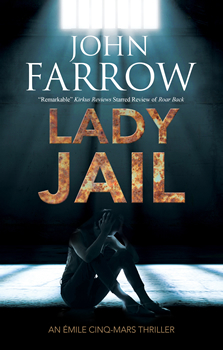

When a prisoner is murdered in 1994 at the Joliette Institution for Women, known by its occupants as Lady Jail, Sergeant-Detective Émile Cinq-Mars is assigned to investigate. But before Cinq-Mars can identify the killer, he must navigate missing millions, the subsequent murder of a prison guard, and an incipient biker gang war. Through it all, Cinq-Mars will have to manage to stay alive, all the while pining for the woman he loves.

This riveting locked room mystery is the ninth John Farrow novel written by acclaimed Canadian author Trevor Ferguson. Ferguson also is the author of seven literary standalones and four plays under his own name.

Of LADY JAIL, Kirkus Reviews says, “Farrow keeps the story’s development as intense as the claustrophobic setting” and calls the story “a wonderful corrective for your pandemic-induced cabin fever.” Lee Child says the series is one of his favorites. “I love Émile Cinq-Mars!”

Recently, The Big Thrill reached out to Ferguson to find out more about LADY JAIL and how he came to write a locked room mystery set in a women’s prison.

“The prisoners had a little book club going, and a few novels of mine had shown up in the prison library,” he says. “Without my knowing, outside supporters of prison women came to my readings and panels, chatted with me, decided that I was up to snuff to go into the penitentiary, and contacted me. I fell for the novelty of it—a crime writer visiting criminals—but received so much more. I was expecting shoplifters or drug pushers, but instead I met a woman who hacked up her daughter, another who killed her own father, another who stabbed her best friend to death for flirting with her boyfriend, another who offed her husband, and when I thought someone had been tagged with a lesser crime, smuggling, it turned out she’d smuggled heavy weapons for the mob. What an extraordinary visit. Our conversation had been bracing and real, intimate and desperate, insightful, honest, and terrifying. Nevertheless, it never occurred to me that a novel might emerge, but years later a story seemed to gel inside me, and whoosh! Another magical ride.”

Farrow celebrates his move across the country to his new home in Victoria, British Columbia, at the Drake pub in 2020.

Character informs Farrow’s stories before plot. “My ambition is to bend my work to suit intricate storytelling that is genuinely unique. First and foremost, I want tales that feel original, compelling, and atmospheric, and at the best of times, fascinating. As distinctive as they are meant to be, they must also be rooted in the lives of the characters. I don’t dream up a plot and shoehorn folks into it; the characters must never be treated as pawns on a chessboard. They reveal themselves to me, just as we find out who we are when in a crisis; they are who they are; and I am not their god. Their natures help create their own dilemmas, and how they emerge is dependent on their devices, not manipulations of plot. I leave them to their own resources and interactions. Unique and distinctive tales, then, is my primary game, where characters present themselves as real people.”

In LADY JAIL, eight women live in a prison group setting created as part of a reform movement. The women’s crimes are not trivial and are similar to the ones Farrow encountered during his prison visit: poisoning, a hatchet murder, fraud, and more. Their daily challenge is to get along and remain alive.

“I knew that I had to pay homage to the lives of the women I’d met inside, being faithful to them even as I created their fictional counterparts,” he says. “All that they’ve gone through, as well as the desperation of their current situation, affected me. Our talk turned to their insistence that they are human, too. They found the concept difficult, as though they’d abandoned their right to their own humanity when they took heinous actions. In most cases, they had wrecked their lives with one momentary outburst. Who among us has not experienced a sudden rage or mindless spasm? In their cases, they lacked a final prohibitive restraint and did what they shall regret forever. And now they are punished. The women can be located in their calamitous moments, but they also can be found away from those terrible seconds. Knitting themselves back together again is a courageous project that provoked the whole of my sympathy, and in a way I was rooting for them and wanted to be part of their quest.”

Hence, empathy for the characters is an important aspect of LADY JAIL. “I wanted empathy for them, without being on the nose, to inform the book, in the way that my experience with the women had informed me.”

Farrow mingles with guests at the Greenwood Centre for Living History, in Hudson, Quebec, in 2011, at the start of a Canada-wide tour of readings with musical accompaniment to promote his historical crime novel River City.

Cinq-Mars also had a real genesis, Farrow says. “I was intrigued by the story of one Captain Jacques Cinq-Mars, who was a major folk hero in Montreal in the ’40s and ’50s, and who’s been accurately described as the Elliot Ness of his time and place. When he retired, the police department was redesigned so that a cop of his power and authority could never rise again—the bureaucrats were taking over—and I decided, essentially, to bring him back in a different era as Émile Cinq-Mars. Moral, intelligent, courageous, but slammed by the establishment and at war with department culture. My guy would use his brains rather than the original man’s brawn, but still be similar with respect to his moral fortitude. My research proved imprecise. I thought the original guy was dead. Big surprise when he phoned me up after the first novel came out. He’s gone now, but we became fast friends, and man, did he have stories to tell! Many are found in River City, where Jacques appears as Armand Touton. He also appears in recent books.”

Farrow began writing after a close brush with death. “I was working in the northern bush of Canada, on the Great Slave Lake Railway, at the age of 16, when I was nearly run down by a locomotive. Without exaggeration, I escaped with my life by less than a millisecond. Living on my own as a teenage runaway, having been granted a reprieve from sure death, I vacated that work camp, and under the northern lights that night wrote on the only paper I could find, which happened to be a Gideon Bible in a ramshackle motel, that I would be a writer, that nothing would stop me, that I would never accept a job I liked as that would deter me, and I signed that vow. Then lived it. From an early age I’d been reading at a high level. Enamored with books, I somehow knew during that dark night of the soul that this is what I had to do with my life that had so luckily and impossibly been spared.”

Farrow (aka Trevor Ferguson) takes his ease on the terrace of the Hudson Yacht Club after a day of sailing.

Sixteen books and four plays later, Farrow is at no loss for words. “If you dig, the ditch you’re in gets deeper, so I keep digging and discovering new strata and new stones to turn over. I’m happiest writing. Miserable otherwise, I write on.”

And we’re so glad he does. At least two more Cinq-Mars novels, plus possible TV and film projects are up next.

- Bruce Borgos - August 8, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: SERVED COLD by James L’Etoile - July 26, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: THE PARIS VENDETTA by Shan Serafin - June 27, 2024