Africa Scene: Stephen Holgate

Exploring an Island of Ghosts

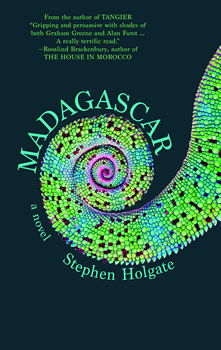

Not many authors start their careers being compared to Graham Greene, John le Carré, and Alan Furst. Stephen Holgate’s two novels—both set in Africa—have reached that mark. Tangier was published last year to acclaim, and MADAGASCAR was released a few months ago.

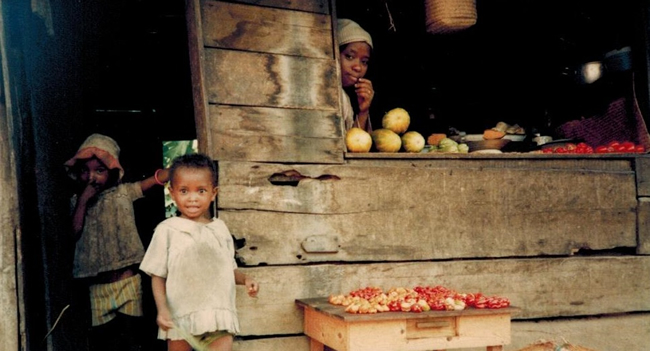

I’ve visited Madagascar and this is not an easy culture to weave into a book. Holgate has done so with sympathy and affection, at the same time constructing a dramatic thriller with rich characters and subtle humor. Publishers Weekly—in a starred review—said: “Holgate has created a memorable lead character and made MADAGASCAR, where the ‘implausible is not only possible, it is mandatory,’ palpable. Le Carré fans won’t want to miss this one.” I have no quarrel with that assessment.

Stephen Holgate is a fifth-generation Oregonian who served as a diplomat at American embassies in France, Madagascar, Morocco, Mexico, and Sri Lanka. He lives with his wife in Portland.

You spent several years in Madagascar as a diplomat and your understanding of the island and its culture comes through everywhere in the book. How much of the novel is based on your own experiences in the country?

I didn’t entirely trust myself to capture the singular qualities of Madagascar with wholly invented incidents. So, more than I have in the past, I based many elements of the novel on stories I’d been told or things I had seen myself. For instance, a story told by a Fulbright scholar about her time in a small village, studying the phenomenon called “tromba women” and the possibility that they might actually be possessed by the spirits of the dead, is based on a conversation I had with a Fulbrighter. Likewise, a visit Knott makes to a rather loopy Malagasy publisher is practically a transcript of a conversation I had with such a man. Finally, the willingness of Malagasy prison guards to let burglars out at night to ply their trade, and the unintended consequences of the guards’ actions, are accurate.

Robert Knott is a diplomat at the U.S. embassy in Antananarivo. He has spent his career abroad and has finally landed up in Madagascar. Having traded a drinking problem for a gambling one, he is hardly the stereotypical successful diplomat. Although a laid-back life would seem to suit him, as he says himself, he prefers to keep the island at a distance. Did you feel that this was a good way of bringing out the culture—through the eyes of an uninterested observer?

Life in the foreign service can be pretty tough. An officer is constantly moving, adjusting to new cultures and working conditions, trying hard to get promoted and move up the hierarchy. It’s tough on families, too, and Knott’s has left him. He has given up on his once-promising career and is simply marking time before he’s forced to retire. Yet he’s still observant and senses the otherness of Madagascar and, unlike many, has retained enough objectivity to understand his otherness to the Malagasy. In fact, he sees himself with frightening clarity. If he’s lost his ability, or perhaps simply the desire, to adjust, he hasn’t lost his mordant sense of humor or his personal charm. And he finds that his efforts to free an imprisoned American and help the man’s Malagasy girlfriend to realize her own dreams of freedom and independence have given his life new meaning.

That starts when Robert has the unpleasant task of visiting Walt Sackett, who is being held in prison essentially for ransom. The elderly man has an attractive young Malagasy girlfriend Nirina from Tamatave, and Robert dismisses her as a gold digger. Yet she is willing to do anything to help Walt. Walt and Nirina are the most sympathetic characters in the book, and the latter part of the story is their quest for freedom. Much against his will, Robert finds himself sucked into their problems. Was this designed to shake Robert out of what you might call his “discomfort” zone?

Ouch! We have to watch this “elderly” stuff. Walt’s a couple years younger than me. Of course, he has the advantage of being a fictional character, so he never grows older.

It’s very hard for Knott to visit Walt in the hopeless squalor of the prison. At a time when he wants to simply go on the shallow glide path toward retirement, he suddenly has responsibilities toward this man, whose fate somehow resonates with the shadows that dominate his own life. Nirina and Walt have what might seem like a mutually exploitative relationship. Neither has been entirely honest with the other. Yet, despite their deceptions, a real tenderness has grown between them. Their mutual plight shakes Knott out of his own self-absorption and puts him on a very dangerous path to possibly free them and, perhaps, redeem himself.

The Malagasy call Madagascar the Island of Ghosts, and most believe that “their ancestors are always present, just over their shoulders, their spirits squeezing into every corner…” Robert understands this, but doesn’t believe in it. Yet it’s central both to the culture and the story. Would it be fair to say that it’s the main theme of MADAGASCAR?

If Robert doesn’t entirely share the Malagasy belief about the immediate and constant presence of his ancestors, it still resonates with him. He’s become his own ghost in a way, the ghost of his former self. So, yes, his confrontation with Malagasy culture, his struggles to help the imprisoned American, serve as an impetus to resurrect himself, find a little redemption, just at the moment when he was ready to give up on himself. (Migosh, I’m making this all sound pretty serious. I like to think it’s actually pretty funny at times, not to mention some passages of sustained action.)

Don’t worry—it’s got great humor and action. And some pretty nasty characters. Robert is being blackmailed by Picard, the owner of the Zebu Room casino, but police Captain Andriamana is the real villain. He is linked to Picard and runs Tamatave province like a fiefdom. Is he the epitome of the corruption that cripples the country?

I don’t want to exaggerate the corruption in Madagascar. It exists and gets in the way of the country’s development. But I’ve seen far worse. A novel is almost always a story of people behaving badly. It is more common to run into good and honest people in Madagascar. And most American diplomats are dedicated and capable. But where’s the fun in that? And tales of good and virtuous people don’t challenge and excite us in the same way. I was once speaking to a foreign journalist, a good guy whom I liked very much. But at one point in our conversation he said, “We know what America is like. We watch Dallas.” (For those not familiar with it, Dallas followed the crimes and intrigues of a fictional oil family in Texas.) I nearly levitated. I tried to tell him that we watch shows like Dallas because our lives are not like that. We’d all murder each other if we behaved like this. Instead, we get to vicariously live out our darker impulses—which often look like great fun—while still leading the lives of good citizens and family members. I like to think MADAGASCAR offers some of these same vicarious thrills, while perhaps shedding a little light on larger issues.

The book features a car chase like no other, and after that the story proceeds at breakneck pace. But the ending has an interesting twist. Did you want MADAGASCAR to have the last word?

I tell people that the main character in the book isn’t Knott or Walt or Nirina, but Madagascar itself. And, yes, at the end, Knott finally embraces the big island and its complex spirit, and in this way, comes to an acceptance of the decency within himself.

Can you tell us something about your next book?

A couple weeks ago I sent off the third novel based on countries I came to know through my foreign service postings. The protagonist of Sri Lanka is almost the opposite of Knott. He is young and consumed by ambition. He is holding back from the embassy the fact that he has made important contacts with the country’s most prominent family. Though he should let his supervisors know right away of his meetings with them, he wants to wait until the relationship has more substance, then spring on everyone a brilliant reporting cable that will cover him in glory and launch his career to the heights he covets. But he soon finds that, rather than mastering these secrets, they are mastering him and he has passed a point of intrigue and conspiracy that threatens his career and his life.

You can find out more about Stephen Holgate and his books on his website.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024