Up Close: James Grippando

Writing About Searing Issues

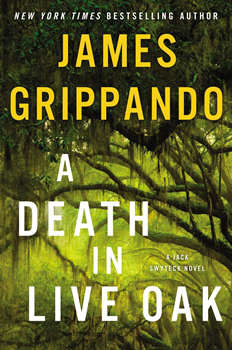

Racism, political corruption, injustice —issues that are, unfortunately, both timeless and contemporary. A DEATH IN LIVE OAK, New York Times bestselling author James Grippando’s 26th novel and 14th in the Jack Swytech series, treats these often-incendiary topics masterfully and with sensitivity, all while keeping the pages turning.

A horrifying lynching dredges up old secrets in A DEATH IN LIVE OAK. Jamal Cousin, the president of a pre-eminent African American fraternity at the University of Florida, is found hogtied and lynched. Cousin’s death ignites a firestorm of protests across the state—protests that ultimately result in violence.

Mark Towson, a fellow student and president of the university’s prominent white fraternities, is charged with Cousin’s murder. Although Towson proclaims his innocence, the evidence against him—including a racist text message sent to the victim from Towson’s phone—continues to mount. The media and public opinion call for his conviction. Against this backdrop, Jack Swytech agrees to defend Towson, risking not only his reputation, but also his own safety and that of his family. In the course of representing Towson, Jack not only pursues the truth behind the Cousin lynching but also discovers a horrifying secret that has been buried for three-quarters of a century.

A DEATH IN LIVE OAK is a powerful story of race, politics, and injustice. Grippando, the winner of the 2017 Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction, has kindly agreed to share his thoughts on A DEATH IN LIVE OAK, his writing process, and his future projects.

A DEATH IN LIVE OAK tells the story of a racially charged hate crime and the lives both lost and shattered in its wake. The novel’s “Author’s Note” discusses certain fact-based antecedents to characters and events in the story, and specifically a lynching in 1944. What drew you to write about these issues? Are any of the other incidents in the book based on fact?

In today’s world of real-time news, it’s virtually impossible to write a “ripped from the headlines” novel. But a story can still be timely, and I can’t think of a more timely topic in this country right now than race. Because race is such a hot-button issue, I felt it was important to ground A DEATH IN LIVE OAK in fact, where possible, and to keep the characters — even the racists — real in all their complexities. The lynching of Willie James Howard in 1944 was so powerful to me that I wrote a dramatic play based on historical fact. It occurred to me, however, that the racism behind that murder and its cover up is creeping back to haunt us. A DEATH IN LIVE OAK provides a contemporary setting that makes us realize that Willie James was not that long ago.

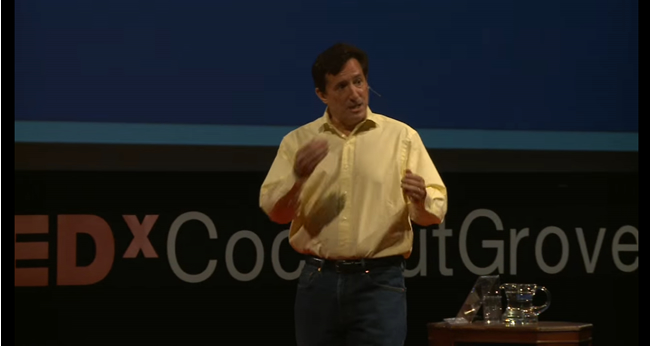

James Grippando speaking at TEDxCoconutGrove at Ransom Everglades School in Miami, Florida, on inspirations required for storytelling.

Your protagonist, Jack Swyteck, is hired to defend a college student accused of the heinous hate crime. As a result, Jack’s reputation and even the safety of him and his family are placed at risk. Why does Jack decide to take on such an unpopular case? More broadly, what motivates Jack?

Jack is not super-cool, super-rich, or super-successful. But he is the kind of guy we all want as a friend — someone we care about enough to celebrate his good days and suffer through his bad ones as if they were our own. Jack’s problem is that he believes that people are basically good, which sometimes gets him into trouble. A DEATH IN LIVE OAK tests Jack’s beliefs in ways they have never been tested before.

Jack is the son of a former governor. At one point, another lawyer involved in the case says of Jack, “Thank God they picked a lightweight.” Why would others believe that Jack is a lightweight? How does his family background motivate him, if at all?

Sometimes a writer throws a line into a story that resonates with fans of the series who understand the layers of complexity in all the various relationships. You’ve hit on one of those lines. Jack made his debut in The Pardon in 1994 as the rebellious son of Florida’s governor, Harry Swyteck. Jack was the young lawyer who defended death row inmates, and Harry was the law-and-order governor who had signed more death warrants than any governor in Florida history. So there was that natural father-son tension in the series from its inception. A DEATH IN LIVE OAK is set decades later, and even though father and son have reconciled, there is always a certain amount of baggage that Jack carries as the son of a politician.

Much of A DEATH IN LIVE OAK focuses on events occurring in college fraternities. Why did you decide to set the crimes in a fraternity context?

I wrote A DEATH IN LIVE OAK while my son was in high school and filling out college applications. As part of that preparation, Ryan and I read various books about college life and talked about them. One of the most important books we read—and one I think should be mandatory reading for parents and their college-bound children—is “Blackballed: The Black and White Politics of Race on America’s Campuses” by Lawrence Ross. I read it, couldn’t forget it, and knew I wanted to set A DEATH IN LIVE OAK on a college campus.

One of the characters in your novel asks whether racism is learned or inherited. How, if at all, does that question inform your story?

You may recall a terrible incident at the University of Oklahoma, where several white fraternity brothers were expelled for leading a racist chant on a party bus. Someone found out where the parents of the expelled students lived, and demonstrators appeared outside the parents’ houses holding signs that read, “Racism is taught.” It struck me. On one hand, we want to believe that no one is born a racist. But if that’s the case, should parents be held to answer for the racist acts of their children? It’s a complex issue.

Putting aside Jack Swyteck, who’s your favorite character in A DEATH IN LIVE OAK, and why?

Jack’s wife, FBI Agent Andie Henning, is one the favorite characters I’ve ever created, and I think she really shines in A DEATH IN LIVE OAK. She first appeared as the lead character in a stand-alone novel called Under Cover of Darkness, where she was an undercover agent infiltrating a cult in central Washington state. She returns to her undercover role in A DEATH IN LIVE OAK, and writing those scenes made me connect with Andie in a way I haven’t in years. The fact that she is now a wife and mother — with so much more to lose —makes her an even more interesting character. I’ve written her into several novels now without Jack (Cash Landing, Need You Now, Money to Burn), but she and Jack really work best as a team.

The town of Live Oak and surrounding areas feel like characters in the novel. Putting aside politics and the law, what about that region of Florida makes it such a compelling setting?

I attended the University of Florida both as an undergraduate and a law student, so I feel a special connection to north-central Florida. I’ve gone “tubing” down rivers in the Suwanee River valley, where A DEATH IN LIVE OAK begins, and I’ve visited the majestic old courthouse in Suwanee County, where Jack Swyteck pleads his client’s case. But you can’t erase the fact that, once upon a time, Florida had more lynchings per capita than any other state in America. It’s world of contradictions, which is fertile ground for a novelist.

A DEATH IN LIVE OAK confronts important social issues. How did you manage to treat those serious issues and still so effectively keep the pages turning?

I’ve covered a broad range of important issues in my novels, from capital punishment to environmental catastrophe, but I hate to read preachy novels, so I don’t write them. The Pardon, for example — the first Jack Swyteck novel— involves capital punishment. I’m proud of the fact that no one can read that novel and guess where I stand on the death penalty. That’s not to say you can read A DEATH ON LIVE OAK and not know how I feel about racism. But telling the story through characters, not caricatures, is what makes the novel work.

Many successful thriller writers have legal backgrounds. Is there something about the practice of law that explains this? Does the fact that you’re still a practicing attorney help your writing process?

It’s a question I hear a lot: Why do lawyers make good writers? If I had to point to one thing, it would be this: motive. Convincing fictional characters have strong and believable motives, and successful lawyers understand what people want, why they want it, and what they’re willing to risk in order to get it. Published lawyer/authors make good use of that understanding.

Could you describe your writing process? Outlining or not, locations where you write, hours per day, how you balance your writing career with a full-time law practice?

I do two things that I would recommend to any writer. First, I never roll right out of bed and go to the keyboard. I walk the neighborhood, drive my kids to school, walk the dog — whatever. That brief pause really does help you realize that the dream you had last night was not really that good, and that it’s probably not the seed for the next Presumed Innocent. Then I start my writing day by self-editing whatever I wrote the previous day. That not only cleans up yesterday’s mistakes, but it also gives you a running start into the next chapter.

Please tell us about your next project.

It’s an exciting year. The play I wrote about Willie James Howard — With L — will get its first public reading in April or June in the south Florida theatre community. This spring I will start teaching “The Law and Lawyers in Modern Literature” at the University of Miami School of Law, and I’m at work on the next Jack Swyteck novel, to be released in 2019.

- Jeffrey Archer - October 12, 2023

- David Bell - July 7, 2023

- Up Close: Daco Auffenorde - October 31, 2020