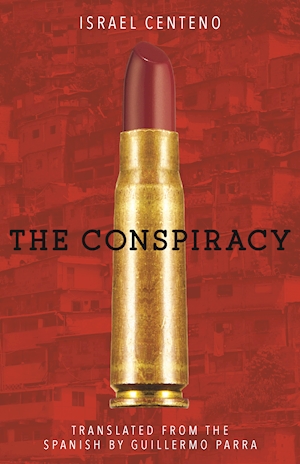

International Thrills: Israel Centeno

A Literary Thriller Taking on Venezuela

By Layton Green

By Layton Green

A long time ago, in what now seems like a galaxy far, far away, I was a young lawyer in a corporate law firm writing a novel in what stolen hours I could find, usually late at night or on weekend mornings. Chasing the dream, I decided to quit my job and move to an island off the coast of Venezuela. The island was called Isla de Margarita, a little slice of troubled paradise that has provided a lifetime of literary fodder. But that’s a story for another time. I fell in love with the country and finished a good bit of my novel in the four months I lived there. When I learned that a decorated Venezuelan novelist—a political exile living in the United States—had written a literary thriller set in Caracas called THE CONSPIRACY, I jumped at the chance to interview him. Though my expectations were high, the novel exceeded them, as did the dialogue with the author. Israel Centeno has given us a frank and fascinating glimpse into his literary career, the circumstances that led to his exile, and the state of affairs of modern Venezuela.

Thanks for taking the time to chat, Israel. We’re thrilled to have you. Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you came to live in the United States?

Caramba! That’s a complicated story. To make it simple, I have been a writer for over 30 years. For a long time I made literature in my own country. My first book came in 1991, my first political thriller. At that moment instead of causing me problems, that novel launched me, it won me the equivalent of our national prize for literature, and established me as a writer. That’s how my career as a published writer began, and that’s continued now for a long time, though I’ve had a lot of challenges. I’ve written more than just thrillers; I combined many genres to participate in the writing of the modern novel. Critics have called it gothic realism. A realism where elements of gothic literature appear in the story. More classical elements. Later, at some point in 2000, it occurred to me to write a novel about someone who had come to power based on the promise of leftist revolution. Really I was thinking a lot about how Hitler came to power, and about Chavez too. Something I had begun to address in my book Exile in the Bowery. About how the radical left had raised arms and essentially become as fundamentalist as the far right. Writing that book had consequences for me. The president himself used it as proof that people had it out for him. A government minister I knew thought that I was relishing in an attempted assassination attempt on him in the 1960s. I was labeled as a traitor, with all that means. In leftist Venezuela, being labeled a traitor is like being called that by the mafia. I was beaten in the street, they attempted to stab me, they threatened my daughters, and broke my electronics when I would return to the country from literary conferences. I was a dangerous man. They considered me a rat. I had no other option but to leave my country and seek exile. That’s how I came to the United States, where I came into contact with City of Asylum, Pittsburgh, a nonprofit organization that has been essential to my stay here, and which commissioned the translation of this novel into English.

How did the Chavez regime impact the arts in Venezuela?

There was a strong break that began with his rule. Until that point the arts in Venezuela had a positive relationship with the government, in which they could critique it quite freely. You see it in our film from the 1970s—movies financed by the government, with an active anti-capitalist, anti-state agenda. Many people said that it was a strategy to let intellectuals vent and have a space to get out their ideas safely.

Chavez had an idea of political loyalty. The intellectual that opposed him, that questioned him, that wrote literature that challenged his regime, would find themselves excluded from the country’s official cultural scene. The Romulo Gallegos Prize, for example, which was sponsored by the government and was considered a big stepping stone toward the Nobel for Latin American writers. As soon as Chavez took over, the quality of the prizewinners changed; it became a strictly political prize. Outside of literature, our national museums started closing. Paintings were mysteriously lost. Museums were repurposed as housing for the homeless.

It wasn’t just me, it was a number of us writers who were threatened, who were officially persecuted by the government. When you dared to go to a fair that was sponsored by the government, you’d be heckled and insulted. That generated a cultural dynamic in Venezuela that encouraged mediocrity. We had 18 years of mediocrity encouraged by the Chavez regime, which had a lot of money to spend on the arts but wasted it almost entirely. People were making a business out of re-selling the paper that the government had purchased to print books but never did. There are some resonances with the Cuba of the early revolution, in about 1971.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? Can you describe your route to publication as a novelist?

I graduated in Spain with my qualifications as a theatre director when I was 19 or 20, and in love with theatre, staging lots of Brecht-style plays. I went to London and I had a crisis: I began to enjoy reading plays more than staging them. When I returned to Barcelona at 21 I wrote my first short story, about a kidnapping. A Caracas story, about a leftist guerilla. I think I lost that story. But at that moment I had the insight that this is what I wanted to do: tell stories. I wrote poetry too, but it was mostly pretty bad.

My first published work was in the cultural sections of our national newspapers. No one in the literary world really knew me, but I finished my first novel, Calletania, and I took it to an editor, who told me he couldn’t publish me at the time for business reasons, but that he would recommend me to the state publishing house, Monte Ávila. They would put your work before a committee of three very demanding readers, and almost no one would get past them. But then they called me back and said that they wanted to publish my novel. It’s a book that has followed me my entire life. It made a real splash, it was a prize winner. It was very popular among the left, and even amongst many Chavez fans, who have written me to say that they wish I had continued writing those types of books. Most Venezuelans at that time would write two novels and disappear. My generation wanted to keep writing, and I have.

Who are some of your favorite novelists, both at home and abroad (past or present)?

I feel like I’ve forgotten everything. I would re-read Romulo Gallego, who reflects a lot on who we are as a country. I think he is under-appreciated within the country of Venezuela. Vargas Llosa until La Guerra del Fin del Mundo. I read him obsessively. I keep Borges by me constantly. Onetti. Speaking of classics: Kafka and Dostoyevsky. There is a North American that is really important to Latin Americans though it seems like he’s been somewhat forgotten here: William Faulkner. The way the Civil War continues to permeate through the culture he describes is something that resonates with me in regards to our history. Paul Auster. Fante. I tried to make myself a Carver fan, but it didn’t stick. I didn’t know if it was him or Lish writing. One other North American I like a lot is Richard Ford.

While THE CONSPIRACY is described as a “poetic thriller,” which it absolutely is, your novel grapples with a number of serious issues, and feels like a novel that is probing the soul of a country. Why did you choose that particular storyline for the novel?

Because I think that at that moment this storyline chose me. I felt very suspicious about Venezuela at that time. It wasn’t just an answer to the Chavez regime, it was a sort of internal struggle with the behavior and internal relationships of the radical left that I knew so well. When Chavez took power, integrating radical parties that had been active only in hiding, that’s what made me write this book. He was reviving my past. People who I believed would never reach power, reached it.

I was also struck by the line in the synopsis declaring that THE CONSPIRACY “challenges the origin myth of South America’s radical left . . .” Can you briefly speak to this, at least for Venezuela?

The radical left in Venezuela, once Marxism appeared, first tried to align itself with the Soviet left. They wanted to incorporate themselves into the institutional structures of democracy. But that didn’t work well. Within the Venezuelan Communist Party, there was a rural guerrilla tradition. We had many militias. Marginalized groups that would rise up every so often—every 10 or 20 years—and stage a revolution. The book addresses how the rigidity—the fundamentalism, if you will—of the radical left, a community I know intimately, is no different from any other form of radical fundamentalism.

I loved THE CONSPIRACY. It’s a beautiful, relentless, thought-provoking fever-dream of a novel. It made me think and feel and research a good number of political theorists. I have not read your other work yet—is THE CONSPIRACY similar to the rest of your novels?

It’s a good start. The only thing that I can see tying them together is the disintegration of our social structures and the resulting dystopia. That’s how I arrive at what I call my Gothic Realism, which I described earlier. I do write thrillers, though not exclusively. My idea is never to resolve our problems, but to use the genre to undress a number of things that are happening in my country, in the reality I have lived, to lay bare how modernity has affected us.

In your own mind, how do you manage the twin objectives of commenting on society at the same time you’re trying to entertain readers and sell books? Does one take precedence over the other?

For the Latin American writer, becoming a best-selling, entertaining writer has always been less important than commenting on society. Having readers is important to me, but the Latin American market is distinct, and though I have been very successful and am published in many countries, I could never live on book sales alone. So I am going to say what I want to say, and I hope to do it in an entertaining way too. If I were from the United States, I might be thinking about my sales more. I want to produce the highest quality literature, and I don’t think much about my audience while I am engaged in doing that, to be honest.

How has Caracas changed during your lifetime?

Caracas turned from a dream into a terrible nightmare. It provokes fear now. The Caracas of my childhood was dynamic and complex and had many problems, but it was a city where all those problems and contradictions invited you to get involved in bettering the city, in making its future as bright as we hoped it could be—a city as vast as its hillsides. The city took a change for the worse, in my opinion, in late 1999, with the Vargas Tragedy, a mudslide that swallowed about 30,000 people and displaced 75,000. It seemed like a physical, geographical embodiment of the city’s disintegration under modernity.

What do you think will happen in Venezuela in the near future?

Venezuela is fucked. If we don’t rebuild the country by demilitarizing and reconsidering our Bolivarian values, things will continue as they are. I am very pessimistic while the military is as powerful as it is. I would be an optimist if our system returned to our civilians, but I don’t see that happening anytime soon, unfortunately. We’ve been left with Chavez’s values, and I don’t think that will change for some time. We need to convince Venezuelans of the importance of civility.

I’m curious about literature in Venezuela—are tastes any different than in the U.S? How do thrillers and mysteries fare?

Not that popular. Some have popped up. Those who write them are accused of writing light fiction. Of course there have been some very popular ones, and political novels are becoming more popular now.

What advice would you pass on to budding novelists?

Two things to keep in balance. Not to forget that fiction must be practiced as one of our fine arts and not to remove your ear from the ground. A good thriller can also be good literature—it shouldn’t be too journalistic. The writer must be tuned in to reality, and we must reinvent our fiction, and remember that the novel is not a TV series or film, but its own rich form.

What are you reading right now?

I just started reading Doris Lessing’s complete works. I am interested in the literature from the ‘70s and ‘80s that responded to communism and radical leftism in Europe. I always go back to Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle, and you can’t go back to Poe without returning to Baudelaire, who Borges said was the real Poe.

What is your next project?

I’m writing a book about a group of insane people in a hospital in Pittsburgh that explores the relationship between our political parties, especially the left, and the cartels. I’m writing it in English and Spanish, one language I know well and one which I am still learning.

*****

Israel Centeno has published novels, short stories, and poetry, and is considered one of Venezuela’s most influential literary figures of the last fifty years. He now lives with his family in Pittsburgh, where he is Exiled Writer-in-Residence at City of Asylum.

To learn more about Israel Centeno, please visit his website.

- International Thrills: James Wolff - June 30, 2018

- International Thrills: Sara Blaedel - April 30, 2018

- International Thrills: Ramón Díaz Eterovic - November 30, 2017