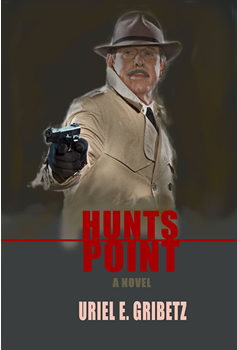

Hunts Point by Uriel E. Gribetz

Uriel E. Gribetz was born and raised in the Bronx, New York, and served nearly thirty years in the public defender’s office in that borough. He took up creative writing at the age of eighteen, at the Bennington Writers Workshop, and has published short stories and essays, along with two novels. His first novel, Taconic Murda, was released in 2014.

HUNTS POINT, Gribetz’s new release, was actually the first book he worked on. Set in his beloved Bronx, the story revolves around a damaged hero named Sam Free who seeks justice for the weak, this time a young man called Jonah who is wrongfully convicted of a grisly murder. HUNTS POINT was released this April by Perfect Crime Books. The Big Thrill interviewed Gribetz about the novel.

Your latest publication centers on a wrongful conviction. Tell us about the young man, and how your life as a public defender helped you create this character.

Sometimes things happen to people that they have no control over and these events shape their lives. Recently I had a seven-year-old client whose mother’s boyfriend murdered his mother and his siblings. The client was stabbed fifteen times, but he survived. How do you get past something like that? I see horrible, awful things that happen to people, yet they are able to survive and go forward.

In the book, Jonah, as a child, was nearly murdered by the Super’s helper in his building. That event shaped him. Jonah’s story is his quest to no longer be a victim of his circumstances. In fact, when Sam Free visits Jonah in prison, Jonah tells Sam that he refuses to be a victim anymore. The strength and resiliency of the human spirit is truly amazing, and I try to capture that with Jonah.

HUNTS POINT is your second mystery/thriller starring Sam Free, a disgraced ex-cop. Tell us about him, and why he takes on this case.

Sam Free became a cop because he wanted to help people, but he lost his way. In the first novel, Taconic Murda, his motives were in the right place, but his actions got him into trouble. In HUNTS POINT Sam has lost almost everything: his career and his marriage is on the rocks. He feels helpless, and at first he takes this case because of the money, but then he continues with it because working to free a wrongfully convicted man takes away Sam’s helplessness and gives him a sense of purpose.

What parts of Sam Free’s character are extensions of you?

His relentlessness. It took me thirty years to get someone to publish my first novel, but I never gave up because writing is my labor of love. I tend to be completely involved in whatever I am working on to the point of obsessiveness, which is not always healthy. Sam Free tends to be like that as well.

HUNTS POINT and your first novel are set in the Bronx, a borough very few people outside New York ever see or even read about. What makes the Bronx a great setting for a thriller?

It’s the people. They are honest and gruff and share an ironic sense of humor. The other thing is our commitment to Bronx justice, which is different than the rest of the world’s view of justice. With Bronx justice, things get squared up in the end, even though not everyone may get what’s coming to them.

In the 1970s, large parts of the Bronx were devastated by poverty and crime. How has the area changed over the years?

Growing up in the Bronx in the 1970s was amazing. Sure times were lean, but we had all the advantages of the cultural revolution of the 1960s. I studied English at Lehman College. It was fantastic. Those times were about joy, not violence. It was before crack and before guns. People weren’t fighting. When I graduated Lehman I took a job working with the multi-handicapped. I made $15,000 a year, and I could afford a large one bedroom on Pelham Parkway.

Today that apartment is $1500 a month but people are still making what I made in 1985, and they can’t afford to pay the rent and buy food. Sure the Bronx is much cleaner. There are no more burning or abandoned buildings, but I think people are poorer. It’s also a more dangerous Bronx than I grew up in because street crime is more prevalent. The young people have little hope. The courts are trying to help. There are many more programs to help the young people and those with drug problems. The Bronx is a stone’s throw from Manhattan but really it is another world in terms of its poverty. The congressional district encompassing the South Bronx is one of the poorest in the country, and it’s in the shadows of the glamorous Yankee Stadium.

Your cast of characters includes minorities. Talk about the challenge of creating minority characters as a white author, and what you do to avoid stereotypes and superficiality.

My wife is from Puerto Rico, and I have had many Spanish friends, that’s why I think I can write about Spanish characters. Also growing up in the Bronx and working in the Bronx I am exposed to many different cultures. I think to write about black and brown characters is to understanding the cultural differences and influences. For example, young men of color get profiled by the police. If you are a young man of color driving a BMW, how many times do you think you will be stopped by the police as compared to a young white man? I think these are things you think about when writing characters.

With any minority, you have to dig deep. I am the child of a holocaust survivor and to understand where I’m coming from you have to have some understanding of that. I am also first generation American on my mother’s side so that I relate to the emigrant/refugee sensibility as well.

Why did you choose criminal law for a career, and why did you stay a public defender instead of going into private practice and making more money?

People who are not lawyers don’t understand that most jobs in law are very boring. Imagine spending hours and hours reading and rereading lengthy contracts filled with arcane and difficult language. I’m not someone who can spend eight to twelve hours at a desk. I need to be up and about. Trial and court work are the most interesting. Criminal law never gets boring, there is always so much going on.

Various books and movies over the years have suggested the practice of law for big-city public defenders is representing a constant progression of the worst people in our society. How do you feel about the people you’ve defended? Is it ever tough to sleep at night?

The toughest case I ever had was a man who had killed his infant son and fed him to the dog. I wrote the appeal. Those pictures of the necropsy kept me up, especially at the time when my kids were very young.

I tend to try to view my role as a defense lawyer very clinically. I try to focus my energy on the strengths and weaknesses of the case and the issues concerning that. I don’t want to know too much about my client’s life, too much about the victim, et cetera. That’s when things get messy. My job is to defend my client to the fullest extent of the law. The prosecutor’s job is to prosecute my client. I tend not to concentrate on the emotional stuff, but rather doing my job as an advocate. This is our system of justice, which works most of the time. Still, even after all that, the truth is that yes sometimes it is tough to sleep.

And while there are many horrible stories of human depravity, most people are not evil. They need help. The root of all anti-social behavior can be traced to a lethal combination of mental illness with drug use or alcohol. Less than one percent of the accused are sadistic sociopaths.

How did your writing evolve between the publication of Taconic Murda and HUNTS POINT?

My characters have evolved. Sam Free is a character I could write for a very long time. I’ve gotten to know him as I have gotten to know the other characters in both books that tend to reappear in the stories.

What’s next for Uriel Gribetz?

I’d like to do some more short fiction and play around with styles. Recently I wrote a piece called “Would you plead guilty to a crime you didn’t commit to stay out of jail?” in second person. I’d like to try to do some more short fiction in that style. I am currently well along in the next Sam Free novel, 1275 Webster, about a seemingly accidental shooting of a civilian by a cop that really isn’t an accident. In this story I am alternating point of views. I think as I write more and more, I am able to experiment more and take more risks. I also want to change the scene in future Sam Free novels. I want to set the fourth novel in Puerto Rico.

*****

Uriel E. Gribetz, who was raised in the Bronx, is the author of a previous Sam Free novel, Taconic Murda. He has been defending the rights of the indigent accused of crimes since 1988, first as a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society Criminal Defense Division in Bronx County and since 1991 as a member of the Assigned Counsel Plan in First Department. He lives in White Plains, N.Y. with his wife and two grown children and two dogs. He is at work on the next Sam Free novel.

Uriel E. Gribetz, who was raised in the Bronx, is the author of a previous Sam Free novel, Taconic Murda. He has been defending the rights of the indigent accused of crimes since 1988, first as a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society Criminal Defense Division in Bronx County and since 1991 as a member of the Assigned Counsel Plan in First Department. He lives in White Plains, N.Y. with his wife and two grown children and two dogs. He is at work on the next Sam Free novel.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024