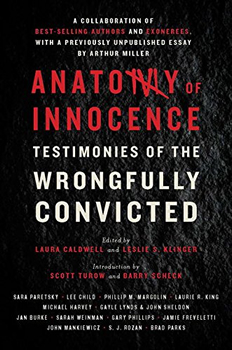

Anatomy of Innocence: Testimonies of the Wrongfully Convicted

Thriller Writers Tell Stories of the Wrongfully Convicted

Thriller writers have long championed the plight of the wrongfully convicted. In 1953, Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason, won an Edgar Award for his nonfiction book Court of Last Resort, about a project that sought to reverse convictions against innocent defendants. The tradition continues in ANATOMY OF INNOCENCE: TESTIMONIES OF THE WRONGFULLY CONVICTED, a new anthology that pairs acclaimed authors with men and women who spent years in prison for crimes they did not commit.

The book is the brainchild of Laura Caldwell, a bestselling mystery author and founder of Life After Innocence, an organization that provides services to exonerees. Caldwell said it was the thriller community’s desire to help the erroneously incarcerated that sparked the idea. “I’d go to ThrillerFest and Bouchercon, and thriller writers always asked how they could help.” That led to Caldwell and Leslie Klinger, an award-winning editor, mapping out a plan for an anthology. The goal was to have great storytellers write pieces about the stages of a wrongful conviction, from accusation to arrest to imprisonment to freedom. “We put out word in the thriller community that we wanted to write stories about exonerees, and the response was immense,” Caldwell said.

The result was 15 vignettes by 15 of the best in the business, including a previously unpublished essay by the late playwright Arthur Miller.

Given the increased public awareness of the problems with our justice system—highlighted by popular shows and podcasts like Making a Murderer and Serial—the plotlines in ANATOMY OF INNOCENCE are all too familiar: stories of bad eyewitness testimony, flawed forensics, inept lawyering, false confessions, and police and prosecutorial abuse. But the book stands out by capturing the human tragedy—with a novelist’s eye for detail. Caldwell noted with surprise that “it took a group of thriller writers to get to the emotional core of these stories and learn things no one else ever had about the exonerees’ experiences.”

S. J. Rozan opens the book with the arrest of Gloria Killian, who spent more than a decade in prison after being convicted as the “mastermind” behind a home invasion murder. Rozan skillfully depicts the “it can happen to anyone” aspect of mistaken convictions, chronicling Killian’s surreal journey from law student to perp-walking accused murderer.

With haunting realism, Sara Paretsky takes readers inside the interrogation—and torture—of David Bates. The abuse led to a false confession that stole 11 years of Bates’s life. Two decades after his exoneration, Bates still suffers from the aftermath. No spoilers here, but Bates told Paretsky things he’d never told anyone about those harrowing hours in a Chicago stationhouse.

Third up is Laurie R. King with a disturbing look at the Kafkaesque trial of Ray Towler, who spent 28 years in prison until DNA tests proved he was innocent of a young girl’s rape. It started with the hapless opening statement by Towler’s defense lawyer and culminated with the judge pressuring Towler to plead guilty. King shows the worst the system has to offer an unmoneyed defendant.

Following his journalistic instincts, former reporter Brad Parks went above and beyond in his piece about Michael Evans, who spent 26 years in prison for the murder of a nine-year-old girl. Parks tracked down a regretful juror from Evans’s trial whose doubts about his guilt later came to fruition when Evans was exonerated. Kirkus called Parks’s account “gut-wrenching” and “the highest level of storytelling.”

David Bates, left, with exoneree Michael Evans, Life After Innocence director Laura Caldwell and LAI adjunct professor Meghan Fahey Monty.

Next, Michael Harvey provides a guided tour through hell: Ken Wyniemko’s first day in a maximum security prison. Writer and filmmaker Harvey conveys a terrifying scene. Wyniemko entered the prison to chants of “Fresh meat, fresh fish!” then settled into his cell in the upper rafters where “all the smells of a prison live.” Like many exonerees covered in the book, Wyniemko had an unwavering belief that the truth would someday set him free: “I knew I wasn’t gonna do 40 years,” he told Harvey. “I knew one day the truth would come out. I didn’t know exactly how or when, but I knew that it would come out.” It took the better part of a decade for that truth to surface.

Lee Child tells the story of ex-Marine Kirk Bloodsworth, the first person ever exonerated from death row by DNA evidence. With his indelible style, Child traces Bloodsworth’s life from boyhood escapades on Maryland’s Eastern Shore to his marine training that helped him survive eight years on death row. Caldwell said she paired Child and Bloodsworth because “Kirk is a real-life Jack Reacher. Tall, former military, and I just knew they’d like each other—and they did.” For his part, Child said that telling Bloodsworth’s story was “a privilege.”

Husband-and-wife team John Sheldon and Gayle Lynds recount the heartbreaking toll incarceration has on an exoneree’s family in their profile of Audrey Edmunds, who operated a home daycare and was found guilty of killing a baby. It took years, but a court finally discredited unreliable evidence on “shaken baby syndrome” that resulted in her conviction. Lynds, cofounder of International Thriller Writers, said she took an editorial role in the story since former prosecutor and judge Sheldon has the legal expertise. (Or, as Sheldon said, “I carried the pen, Gayle carried the whip.”) Lynds said that “Audrey lost her marriage, lost her children, and she’s never received a penny. It’s wrong.” Though Lynds and Sheldon are angry that Edmunds has received no compensation for the injustice, they both were moved by her lack of bitterness. “It’s quite remarkable given what she’s gone through,” Sheldon said.

Jan Burke’s account of Alton Logan’s case has a twist befitting a thriller. Logan spent twenty-six years behind bars for murder never knowing that someone else had confessed to the crime. The problem: the killer had told only his lawyers and refused to allow them to reveal the truth until he died. The attorney-client privilege, which is designed to provide the best defense for one man, meant the downfall of another. Burke said, “[t]he experience of participating in ANATOMY OF INNOCENCE was one of the most moving of my life. No exaggeration.”

Editor and writer Sarah Weinman illustrates how wrongful incarceration can quite literally eat at a person’s soul, highlighting Ginny Lefever’s struggle with depression and food addiction while in prison. Lefever, wrongfully convicted for murdering her husband, told Weinman: “My fear was not about whether I would ever get out, but that when I did, there wouldn’t be enough left of me to put the pieces back together again.”

Having represented clients in more than thirty homicide cases, lawyer-turned-bestselling-author Phillip Margolin knows his way around the judicial system. But even Margolin was impressed with Bill Dillon, who’d still be incarcerated if he hadn’t become his own jailhouse lawyer. After Dillon had nearly lost all hope, an elderly inmate in the prison library told Dillon about DNA testing. Dillon’s handwritten motion eventually led to his freedom after serving twenty years for a murder he did not commit.

Gary Phillips exposes the agony of the slow turning wheels of justice. After his erroneous conviction, Jeff Deskovic spent his teens, twenties, and early thirties watching appeal after appeal—seven in all—rejected. When a long-shot effort by the Innocence Project helped prove that he did not kill a classmate, Deskovic couldn’t believe they were letting him out. Phillips said, “You’re soberly reminded that for some, often those without the resources or wherewithal to mount proper defenses, once the attention of the criminal justice system has determined an individual is culpable, how hard it is to reverse what might well be a false or incomplete narrative.”

Lawyer-author Jamie Freveletti proves that a good lawyer can make a difference. For Antione Day, salvation arrived in the form of Howard Joseph, a soon-to-be-retired real estate attorney who decided to do some pro bono work in his twilight years. Freveletti paints an irresistible picture of the duo: “[An] African American rhythm-and-blues musician convicted of murder, and the elderly attorney in a crooked tie given to wearing corduroy moccasin house slippers and a rumpled trench coat.” The odd couple proved Day’s innocence. Freveletti said, “Howard Joseph . . . was truly an angel who appeared seemingly out of nowhere and changed many lives. Meeting and working with Antione, who has surprisingly little bitterness over what happened to him, taught me the true meaning of forgiveness.”

Screenwriter and House of Cards producer John Mankiewicz recounts the story of Jerry Miller, the 200th person exonerated by the Innocence Project based on DNA evidence. “I was 21 when the cops picked me up for questioning” Miller said. “When I got out, I was 47 years old.” Mankiewicz captures the sense of loss during those years, and the awe of a man locked up for so long then exonerated and thrust into the media spotlight.

Fittingly, Laura Caldwell closes the anthology with a touching description of Juan Rivera’s life on the outside after wrongly serving 20 years in prison—from his mornings watching the sunrise and gazing in wonder at his baby daughter to his daily thoughts about the little girl he was erroneously accused of murdering.

Each story in ANATOMY OF INNOCENCE is unique and compelling in its own right, but some common themes emerge. The living hell of prison. The loss of friends and family while incarcerated. The often fortuitous circumstances that lead to exoneration. But perhaps the most noteworthy is how often exonerees rejected bitterness and turned their focus toward the future and helping others.

With introductions by former prosecutor Scott Turow and defense lawyer and Innocence Project cofounder Barry Scheck, the book maintains balance, noting that injustices are not always the result of malfeasance. Said Caldwell, “The lesson is that our system is made up of humans, and mistakes are inevitable.” In the end, she and coeditor Klinger hope that readers come away with both a deeper understanding of the price of the flawed justice system and an urge to help. One way to do so is to buy the book: proceeds go to Life After Innocence to help exonerees begin their lives anew.

- Anatomy of Innocence: Testimonies of the Wrongfully Convicted - February 28, 2017

- Far From True by Linwood Barclay - March 31, 2016

- Between the Lines Interview with New York Times bestselling author Gayle Lynds - December 30, 2015