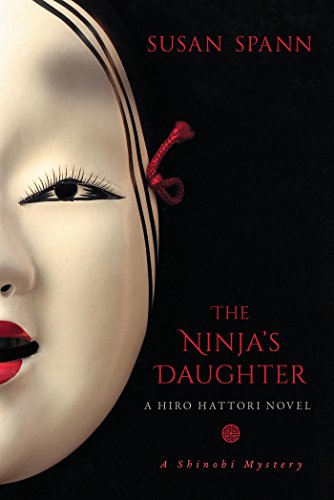

The Ninja’s Daughter by Susan Spann

Kyoto, 1565: A ninja named Hiro Hattori brings murderers to justice, with the help of a Portuguese Jesuit priest, Father Matteo. This is the premise of the engrossing Shinobi Mystery Series written by Susan Spann. Her acclaimed 2013 debut, Claws of the Cat, was followed by Blades of the Samurai and Flask of the Drunken Master.

In the fourth book, THE NINJA’S DAUGHTER, an actress is found dead on the banks of Kyoto’s Kama River, and no one seems to want to get to the truth—except for Hiro and Father Matteo.

We caught up with California native Spann, whose interests range from martial arts to seahorses, to find out more:

For the setting of a novel, what drew you to mid-16th century Japan as opposed to other time periods in that country?

My original inspiration for the series was “most ninjas commit murders, but Hiro Hattori solves them.” Real, historical ninjas (also called “shinobi” in Japanese) reached the apex of their power during the 16th century, which made it a natural place to set the series. I also wanted to include a Portuguese Jesuit as Hiro’s partner sleuth and to offer a “Westernized” filter for Japanese culture. Japan was closed to foreigners for much of its history, but Portuguese priests and traders lived and worked in Japan during much of the 16th century. Fortunately for the series, the timing worked from both angles.

What do other novelists writing books set in Japan sometimes get wrong that drives you crazy?

Fortunately, many of the authors currently writing novels with Japanese settings have an excellent grasp of the history and culture, so I don’t find much to criticize. (In particular, I love Barry Lancet’s Jim Brodie novels and I mourned the end of Laura Joh Rowland’s Sano Ichiro series.)

One cultural issue I notice a lot in other places is the misrepresentation of ninjas in popular culture. Real ninjas were spies as well as assassins and weapons experts—much more interesting than the black-pajama-clad supermen you see in movies and TV. While the Hollywood variety is fun in its own way, I prefer to represent the shinobi more realistically in my novels. The truth is actually far more exciting than popular culture’s version!

Most people reading these books are not knowledgeable about the culture. You have an outsider in the series the reader could identify with and yet he is not the main POV character of the book, an insider is. How did you come to that decision?

Short answer: the protagonist chose me. From the inception, I wanted to write from Hiro’s pragmatic point of view. He’s an unrepentant assassin with a strongly ironic sense of humor, and as a shinobi he stands a bit outside the social order. It isn’t always an easy viewpoint to write from, but I love the challenge.

Father Mateo acts as Hiro’s foil and the reader’s cultural filter—and truly, he and Hiro act as joint protagonists in almost every way. That said, only an insider would have been able to navigate the culture and solve the crimes that occurred in the tightly-regimented society of 16th century Japan, so when it came to choosing a point of view protagonist, Hiro had to take the lead.

What is the greatest advantage to writing a historical mystery series? Disadvantage?

The best part is taking readers on a journey to a dangerous and compelling time and place most people know little about. I fell in love with Japanese history, language, and culture while pursuing my undergraduate degree in Asian studies at Tufts University many years ago. Most people’s eyes glaze over when I wax poetic over 16th century kimono designs at dinner parties . . . but drop that kimono onto a teenage teahouse girl accused of murdering her samurai patron and suddenly everyone wants to know more.

The biggest disadvantage is my lack of a functional time machine, which means I have to work hard to ensure I’m getting the details exactly right. Fortunately, I love research, so even the “disadvantage” is just an excuse to spend more time in books, consulting with experts, and (best of all) visiting Japan.

How do you work into your book moral beliefs that are difficult for modern readers to accept, such as the murder of an actor’s child is not worth investigation because of how low the actors are regarded?

History is full of misguided and mistaken opinions, and historical novels that portray these times and places accurately have to address this moral issue. Fortunately, my protagonists both have highly-developed senses of justice—Father Mateo’s shaped by his Christian faith and Hiro’s derived from a loathing of bullies and several experiences in his (admittedly fictitious) childhood.

Also, the nature of mystery novels often allows me to give the less-pleasant moral positions to killers and secondary characters, rather than my protagonists and the people they seek to aid. Since mysteries generally end with the villain getting what he or she deserves, I sometimes choose to give the most morally difficult historical opinions to people who end up dead or punished. Cheating? Maybe – but satisfying too.

How do you share historical detail while keeping the pace taut?

Ninety-nine percent of my research doesn’t make it into the novel, and 85 percent of the details have to end up on the cutting room floor. I try to keep my descriptions vivid, short, and accurate—in keeping with Japanese aesthetics as well as the needs of a fast-paced novel.

Can you share any insights on writing accessible dialogue set in a society so complex?

Building a foreigner into the primary cast allows me a little leeway, because Father Mateo doesn’t always understand the finer points of Japanese culture. While I have to be careful not to overuse that trick, it does let me explain a few of the puzzling words and concepts readers encounter in the dialogue.

Sixteenth century Japan was a highly formal culture, with stringent rules for the way people communicated with one another. I’ve tried to keep my dialogue within those rules, but omitted some of the more archaic sentence structures. (There’s also a glossary of Japanese terms at the back of the books.)

You are an author and a publishing attorney. What is the one thing you most wish authors would do?

Value their work enough to treat their writing like a business, and to learn about the publishing industry, so they don’t fall prey to scammers and others who seek to take advantage of the innocent. Writing is a passion, and an art, but publishing is a business. Writers need to treat it as one, even before they ever publish a book.

What from your perspective helps authors build a readership? What can they do independent of their publishers?

One of the best ways authors can build a readership, in my opinion, is getting to know other people—both in “real life” and on social media. Attend writers’ conferences, other authors’ signings, and local literary events. Meet people on Twitter and interact on Facebook, or on whatever other social media platforms you enjoy.

Participate not as “someone with a book to sell” but as a real person who cares about other people, what they’re doing, and the interests you may share. Advertising is all well and good, but when you go out of your way to make friends, you’ll find that your friends will very often become your readers too.

*****

Susan Spann is the author of three previous novels in the Shinobi Mystery series: Claws of the Cat, Blade of the Samurai, and Flask of the Drunken Master. She has had a lifelong love of Japanese history and culture. When not writing, she works as a transactional attorney focusing on publishing and business law, and raises seahorses and rare corals in her marine aquarium.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018