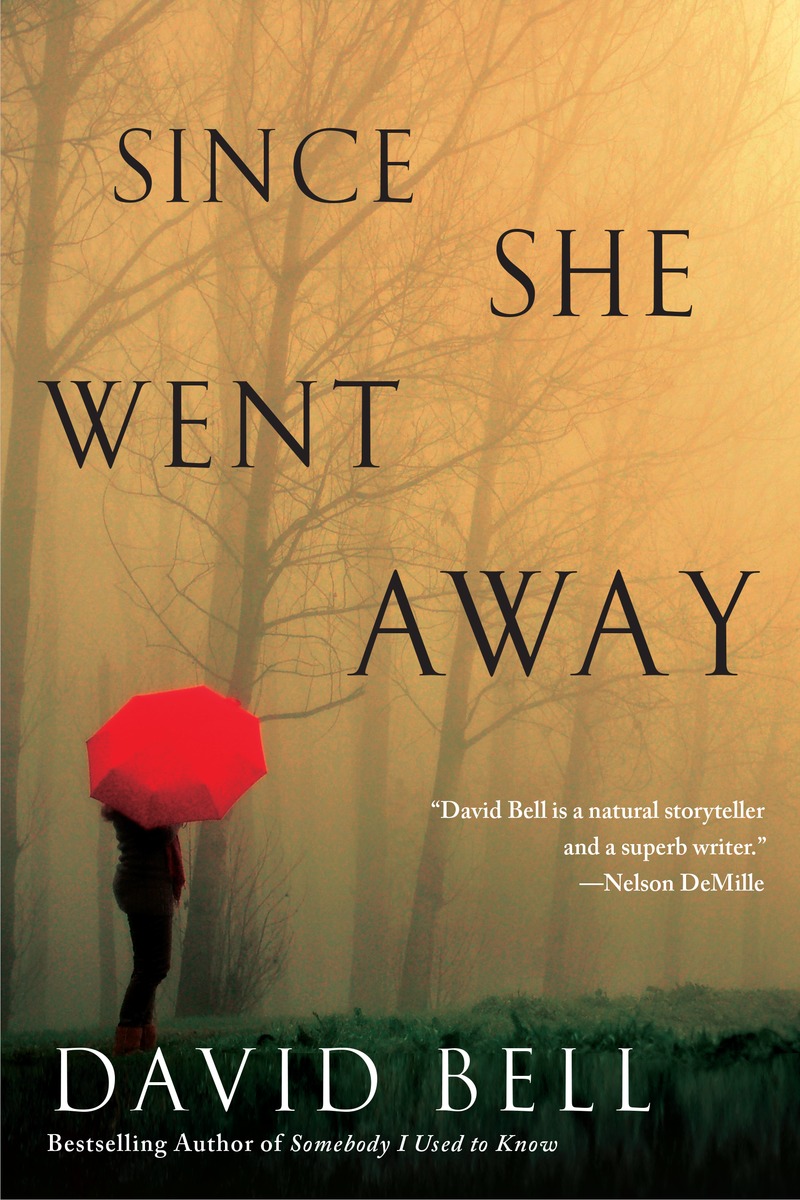

Since She Went Away by David Bell

“Graduate school in creative writing can teach discipline, it can help a writer make contacts, and it can put a writer in a supportive environment,” says associate professor David Bell, who holds an M.A. and Ph.D. in creative writing. “But it’s not a magic bullet,” adds the bestselling author. “A writer still has to be able to tell a good story and have the discipline to keep writing when school ends.”

David Bell’s latest suspense novel is SINCE SHE WENT AWAY, a fast-paced page-turner that Romantic Times has named a Top Pick for June. Women are disappearing in Hawks Mill, including Jenna Barton’s best friend and her teenage son’s new girlfriend. Jenna begins to wonder how many secrets one small town can hold as she desperately tries to untangle the truth.

Although Bell and I both attended ThrillerFest X last summer, we didn’t manage to meet until now. But I knew we’d get along when I discovered our shared fondness for cemetery walks.

Your first published works were short stories. How did writing them prepare you for the transition to writing novels?

Most writers start out writing short stories for practical reasons. In the length of time it takes to write one novel a writer could produce five, ten, or fifteen short stories. And short stories can teach useful skills for the suspense novelist—efficiency, concision, control. But, in the end, the only thing that can teach someone to write a novel is to write one. I tell my students they have to write a bad novel before they can write a good one, so get started on that bad one before it’s too late.

You’ve written eight novels in as many years. I saw a BBC documentary in which Scottish crime-fiction author Ian Rankin explained his strictly detailed schedule for writing a novel a year. Do you have a regulated routine?

In order to write a book every year—and continue to work my day job as a college professor—I have to be disciplined. Since I have summers and holidays mostly free from my teaching job, I do a lot of writing then. During the academic year, I spend time generating ideas, working on outlines, and revising. I’m a creature of habit. I like routine, so this works for me.

I always make an outline. I can spend as much time on an outline as I spend writing a draft of the book. By working out as many character and plot issues in the outline, the writing of the book is a little easier. It’s a road map to where I want to go. Still, surprises crop up. My outline for SINCE SHE WENT AWAY had a totally different ending. The ending of the published book just came to me as I wrote. If I’m surprised then I figure the reader will be surprised as well.

Any particular reason that you prefer writing domestic suspense, as opposed to, say, police procedural or private investigator driven stories?

I love reading procedurals and P.I. novels, but I think writers have to find their own landscape, their own people to write about. I feel most comfortable writing about ordinary people in extraordinary situations. In other words, domestic suspense. If I tried to write an Ed McBain-type novel, it might feel forced. And I might feel like a fraud doing it. But I’m happy to read Ed McBain all day.

You appear to have an affinity for small town settings like Hawks Mill. I grew up in a small town and couldn’t wait to get away. Does small-town life work better for the purposes of domestic suspense? Or are you writing what you know?

I grew up in Cincinnati in an old neighborhood close to downtown, so when I was a kid I had no concept of small-town life. I always thought I’d write gritty, urban tales like Elmore Leonard or Richard Price. But I’ve spent the past decade living in small or mid-size towns, so I am writing what I know. And people assume nothing bad ever happens in small towns, that they’re somehow safer than a big city. In some ways I’m playing against that stereotype. Anyone who has ever lived in a small town knows it’s not true anyway.

The point of view switches back and forth between Jenna and her 15-year-old son, Jared. Did you encounter any challenges writing from a contemporary teen’s perspective?

The experience of being a 15-year-old is pretty universal. I certainly remember those times well, as much as I’d like to forget. You’re right that some of the contemporary, superficial details—the clothes, the music, the video games—might have changed, but it’s pretty easy to find a teenager to ask research questions. Teenagers love telling “old” people when they’ve gotten something wrong.

The role of the media is central in your story, especially in casting suspicion on Jenna. It seems to highlight how today’s media shift to more hyperbolic reporting is similar to tabloid news of the past. Is this a deliberate critique?

I didn’t set out with a critique in mind. I was simply trying to think of ways to make Jenna’s life more difficult, to increase the pressure and guilt she feels over the disappearance of her friend. Today’s media—both traditional and social—can do a lot of good things in terms of spreading the word about crimes and missing persons. I’m sure the media have contributed to countless successful recoveries and prosecutions. But the bad comes along with that. Our overhyped, click bait obsessed world means that everyone is screaming for attention, and so restraint and critical thinking often take a back seat. So, yes, the book ends up offering a critique of a certain kind of media outlet. I think if the book wasn’t engaging with—and commenting on—the world around us I wouldn’t be doing my job as well as I could.

*****

David Bell is the bestselling and award-winning author of Somebody I Used to Know, The Forgotten Girl, Never Come Back, The Hiding Place, and Cemetery Girl. He’s an associate professor of English at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

David Bell is the bestselling and award-winning author of Somebody I Used to Know, The Forgotten Girl, Never Come Back, The Hiding Place, and Cemetery Girl. He’s an associate professor of English at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

To learn more about David, please visit his website.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024