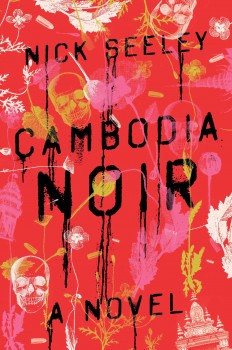

Cambodia Noir by Nick Seeley

By J. H. Bográn

By J. H. Bográn

PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA: the end of the line. Lawless, drug-soaked, forgotten—it’s where bad journalists go to die. For once-great war photographer Will Keller, that’s kind of a mission statement: he spends his days floating from one score to the next, taking any job that pays; his nights are a haze of sex, drugs, booze, and brawling. But Will’s spiral toward oblivion is interrupted by Kara Saito, a beautiful young woman who shows up and begs Will to help find her sister, June, who disappeared during a stint as an intern at the local paper. Cambo offers a hundred kinds of trouble a young reporter could get mixed up in—but June came with secrets and terrors of her own. Cambodia is not the only place she’s traveled, or the worst, and the more Will learns about her past, the more danger they both are in . . .

When you read the above description, you immediately feel transported to an eerie state of mind, I know I do. That’s part of the fun of reading noir thrillers; the inner conflict is usually more relevant than any bullets flying. It is also compelling. You must find out what happens next. Welcome to the world of debut author Nick Seeley. This is CAMBODIA NOIR.

Was there a particular incident in your life as a journalist that triggered CAMBODIA NOIR?

In 2003, I worked briefly in Cambodia as an intern at a daily newspaper—much like June does in the novel. Wild, sometimes terrifying things were happening all around me: drug busts, political murders, a disputed election. The country and its people had faced unimaginable tragedy, and were still being exploited by global markets, corrupt politicians, sex tourists, and more. Being in the middle of all that was doing strange things to my head, and I wanted to try and capture the feelings evoked. This book was my way to do that. It’s a fantasy, for which I created a set of fictional incidents that roughly parallel some of the things I saw happen at the time. My author’s note at the end of the novel explains a bit more of this.

The “noir” as part of the title pretty much defines the sub-genre the novel belongs to, I’d like to know if the story was “noir” since its inception or was it something that grew organically later on.

Figuring out that this was Cambodia “noir” was what eventually enabled me to write the book. I knew I wanted to write something—and I didn’t want it to be a thinly-veiled autobiography, a holier-than-thou travelogue, or a compendium of all the unconfirmed stories I couldn’t write for the paper (basically an attempt to do journalism without accountability). My way out was to focus on writing the kind of book I like to read, to situate my story in the genre that meant the most to me, in the tradition of Chandler and Cain and Ellroy. Flawed, violent protagonists; beautiful and dangerous love interests; lost children, pretty crooks, corrupt officials, vast and frightening conspiracies…

How difficult was the transition from writing facts as a journalist to writing fiction?

In some ways it’s very easy. There’s a bright line between the activity of journalism and the activity of fiction writing. They depend on some of the same basic skills and tools, but they’re totally different activities, with different objectives, different histories and canons, different rules and conventions. It’s like cabinetmaking and shipbuilding.

But some things are difficult. One thing that I do take from journalism into fiction is the sense of responsibility not to misrepresent the world or its people. And it’s tough! Every book is a hologram: a multi-dimensional image that creates in a reader’s mind an entire alternate universe, from the laws of physics down to traffic regulations. And in some way, those readers are going to assume, at least subconsciously, that that universe is like the universe we live in. That’s true even if you’re writing exclusively about aliens in a galaxy far, far away. (Stop and think for a second about how many of the things you think you know are actually based on things you’ve seen on TV shows or read in novels. Do you actually know anything, really, about how police officers work, or E.R. doctors, or spies, lawyers, soldiers? For most of us the correct answer is “no,” and yet we think we know a lot—from fiction.)

Now, on the one hand, as an author you want your fiction to be believable. You want your cops to act like cops, and your soldiers to act like soldiers. But what does that really mean, when you get down to it? What does a police officer act like? Is everyone the same? Soon you’re asking questions like: “On a probability curve, how much of an outlier is my character?” and “Am I presenting this event as normal, or as unusual, or as totally-nuts-but-it’s-happening-anyway?” And you’re sliding down a dark hole with no bottom, because you’ve forgotten the truth, which is that if there is a bright line here, it’s only between “what actually happened” and “what didn’t.” All stories are lies, yet we all mistake them for truth. So how do you write a bunch of lies about a place, without doing too much violence to the reality? That’s the really hard question; I don’t think it has a good answer.

Will you be attending ThrillerFest?

I’d very much like to, it’s a terrific event. I actually met my agent at AgentFest in 2013, and he’s been amazing. It’s not just that without him Cambodia Noir would never have seen the light of day, it also wouldn’t be nearly as strong a book. But I don’t even know what part of the world I’ll be based in, come summer, or what I’ll be working on, so it’s hard to say if I’ll be able to make it to New York

What’s next? Will there be a sequel?

I have no plans right now to return to this setting or these characters. I’m working on a new project, set in another part of the world, that takes what I hope will be a very different approach to reinterpreting noir tropes in a contemporary setting.

*****

Nick Seeley is an international journalist who got his start in Phnom Penh. Since then, he has spent more than a decade reporting from the Middle East. His work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy magazine, Middle East Report, and Travelers’ Tales, among other publications. He is also the author of the nonfiction Kindle Single A Syrian Wedding, about life in a refugee camp in Jordan. Cambodia Noir is his first novel.

Nick Seeley is an international journalist who got his start in Phnom Penh. Since then, he has spent more than a decade reporting from the Middle East. His work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy magazine, Middle East Report, and Travelers’ Tales, among other publications. He is also the author of the nonfiction Kindle Single A Syrian Wedding, about life in a refugee camp in Jordan. Cambodia Noir is his first novel.

- Mark Greaney by José H. Bográn (VIDEO) - June 27, 2024

- Brian Andrews & Jeffrey Wilson by José H. Bográn (Video) - May 23, 2024

- Classic Thrills: THE DAY OF THE JACKAL by Frederick Forsyth - May 10, 2024