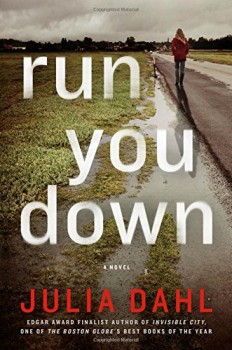

Run You Down by Julia Dahl

I met Julia Dahl when we shared a panel at Bouchercon Long Beach. I’d heard rumors and whispers about her first novel Invisible City—all of them extremely positive—but hadn’t yet read it.

After meeting Dahl and listening to her on the panel, I had no choice but to immediately purchase the novel. To say I wasn’t disappointed is a huge understatement. Invisible City is one of those rare first novels that gets everything right—from character to setting to plot to tone to emotion, Dahl nailed it. Her exploration of the Hasidic community and of herself is all there on the page.

We have since become pals and I’m now reading her excellent follow up, RUN YOU DOWN.

I recently asked Dahl some questions that will give readers insights into the novels—and the author behind these great books. Here, she answers for The Big Thrill.

How does a woman from Fresno end up in Brooklyn living over a custom-made cutlery shop?

Getting out of Fresno was essentially the motivating factor of my childhood and adolescence, and for as long as I can remember I’ve wanted to live in New York. I visited once as a nine-year-old and fell in love—plus all my favorite movies as a girl (Working Girl, Big, Splash, Baby Boom, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, etc) took place here. It just seemed like anything was possible in NYC. So, after college, I got an internship at Entertainment Weekly, a roommate, and an apartment on East 39th Street. I’ve been living the dream ever since.

The knife shop is also a love story: I met my husband when we were both getting MFAs at the New School in 2003. Both of us had written novels and neither of us could sell them. I turned my focus to building my career as a reporter, while my husband decided to start working with his hands. One day, he used one of his grandfather’s old tools to make a knife. And then he made another. Eleven years later, people all over the world are dying to get their hands on his knives. We opened a little shop in Gowanus and rent the apartment upstairs. Again, living the dream.

You and your protagonist, Rebekah Roberts, have some fascinating things in common. What are they and how did they shape the direction of the series?

Rebekah and I are both the children of Jewish mothers and Christian fathers. Rebekah’s mother abandoned her, so she doesn’t know much about her Jewish heritage, but I was raised in a home that celebrated both faiths. My parents are both very religious—just different religions. We did Christmas and Hanukkah, Easter and Passover. Sometimes I went to Sunday school at church, sometimes at the temple. It never seemed odd or contradictory to me, but it does to other people. I consider myself Jewish (as my grandmother always said: “There are enough Christians in the world, Julia. We need more good Jews.”) but I’m not very religious. Still, perhaps because of my upbringing, I am constantly thinking about what it means to be a Jew—something Rebekah also grapples with.

Rebekah and I are also both reporters. She works for a fictional New York City tabloid called The New York Tribune, and for three years I worked as a reporter for The New York Post—now I’m at CBS News. My time at The Post very much inspired Invisible City. Every day I was sent to a different neighborhood to cover a different crime and had to ingratiate myself with a different group of people—often on the worst day of their life. Morally, it was a difficult job—and in Journalism school, they don’t teach you how to approach a mother who has just found out her child was murdered.

I was thirty when I started working at The Post—I’d been to graduate school and worked in the media industry for eight years. But many of colleagues were just out of college and we didn’t have much in the way of supervision or guidance from editors. We were just told: go get the quote. I decided to write a character who was young and doing this job because I wanted to explore the perils of doing such difficult work without adequate maturity or understanding of the power she wields as a reporter.

Politics and religion are dangerous topics for anyone to take on, but you’ve chosen to take them on in a very personal way. Why these two topics and not more traditional ones?

For me, politics and religion are pretty traditional—controversial, yes, but definitely fodder for many interesting ideas and stories. Honestly, I wasn’t going to spend six years of my life writing about something that I didn’t think was important—and I think that the politics of how law enforcement interacts with this powerful, insular religious group is very important. It impacts thousands of lives.

The New York Hasidic Jewish community is very male oriented and insular. What fascinated you about the community and how did you gain access?

Where I grew up, there were no ultra-Orthodox Jews. I didn’t even know Hasidim existed in the United States until I moved to the east coast. When I moved to Brooklyn in 2007, I started seeing more and more men in black hats and women in wigs and I couldn’t help but think: they’re Jewish, like me, but not at all like me. I wanted to know more.

It took years to get access to people in the community, and mostly it came through relationships formed with people who had left the community and were living more modern lives, which meant they were open to talking to me about their upbringing—and later introducing me to family and friends.

Rebekah has an unusual relationship, if I can call it that, with her mother. Tell us a little something about that.

Rebekah’s mother, Aviva, grew up Hasidic in Brooklyn and then abandoned her and her father just a few months after Rebekah was born. So for most of her life, Rebekah had no idea if her mother was alive or dead, and that uncertainty, coupled with the pain of her rejection, created a deep hole in her. Sometimes she plugs it up with anger at her mother, but mostly she’s just desperate for some kind of information—any kind. At the end of Invisible City, Aviva finally reaches out to her daughter, but as RUN YOU DOWN begins, Rebekah is paralyzed by the fear that whoever her mother actually is might be scarier—and harder to deal with—than the ghost she’s created in her head.

*****

Julia Dahl writes about crime and criminal justice for CBSNews.com. Her first novel, INVISIBLE CITY, was a finalist for the Edgar, Thriller and Anthony Awards for Best First Novel and was named one of the Boston Globe’s Best Books of 2014. She was born in Fresno, Calif., and now lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Julia Dahl writes about crime and criminal justice for CBSNews.com. Her first novel, INVISIBLE CITY, was a finalist for the Edgar, Thriller and Anthony Awards for Best First Novel and was named one of the Boston Globe’s Best Books of 2014. She was born in Fresno, Calif., and now lives in Brooklyn, NY.

To learn more about Julia, please visit her website.

- Run You Down by Julia Dahl - June 30, 2015