Features International Thrills: Antony Dunford

Africa Scene: Defending African Wildlife in the DRC

The Big Thrill Interviews Antony Dunford

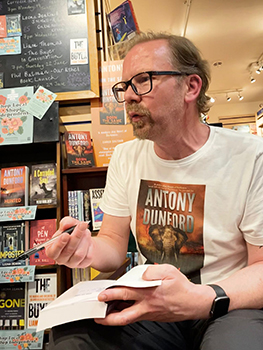

Antony Dunford is a crime writer from Yorkshire in England. Among his five degrees, he has one MA in creative writing and one MA in crime fiction, and he’s been writing stories since he can remember. Antony’s impressive debut novel, Hunted, set in Kenya and published in 2021, was shortlisted for the UEA Little, Brown award, long listed for the CWA John Creasey New Blood dagger and the Grindstone Literary Prize, and enthusiastically received by critics and readers alike.

Antony Dunford is a crime writer from Yorkshire in England. Among his five degrees, he has one MA in creative writing and one MA in crime fiction, and he’s been writing stories since he can remember. Antony’s impressive debut novel, Hunted, set in Kenya and published in 2021, was shortlisted for the UEA Little, Brown award, long listed for the CWA John Creasey New Blood dagger and the Grindstone Literary Prize, and enthusiastically received by critics and readers alike.

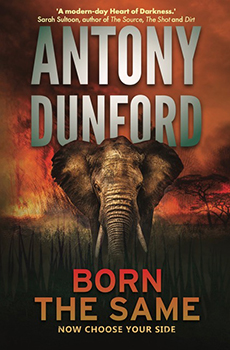

BORN THE SAME was released this year and is a prequel to Hunted.

The new novel is set in the Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The park borders on southern South Sudan, an area crawling with lawless militias. It could be one of the most dangerous places in the world outside a formal warzone. BORN THE SAME has a powerful sense of place—pelting rain, massive trees, grass higher than a man, vicious warlords.

Antony, how did you go about researching the area and its people?

My first introduction to Garamba was in the book Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine, published in 1989 to accompany the Radio 4 series of the same name. The premise of the book is that Mark (a biologist) selected nine species that were on the verge of extinction, then Mark and Douglas went to see the animals in their natural habitat, and Douglas (the famous novelist) wrote about the experience. Of those nine species, two were in what was then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—the Mountain Gorilla and the Northern White Rhino, the last 20 or so of which could be found in Garamba National Park.

On a map of the DRC, Garamba is a tiny dot tucked away in the north-east corner, on the border with South Sudan. Closer up, it looks a lot bigger—5,200 square kilometers/2,000 square miles. British newsreaders would contextualize that by saying “An area a quarter of the size of Wales.”

Douglas and Mark travelled to Garamba where they met Kes Hillman Smith. Kes and her husband were leading a team of conservationists in an attempt to recover the Northern White Rhino population from a then recent (early 80s) low of 15 animals.

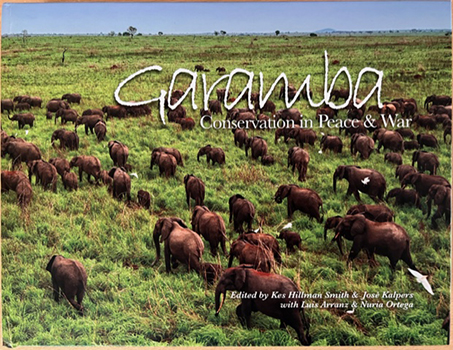

When I decided to write BORN THE SAME, I learned that Kes Hillman Smith and the conservationists she worked with in Garamba had written a book called Garamba: Conservation in Peace and War. A fantastic, sweeping, inspirational and heart-wrenching work about the whole ecosystem of the park, including its history back to the foundation of the park and beyond. It is written by people involved in the management, protection, and running of the park, and is packed with photos, facts, analysis, and narrative. My research started there.

I also needed moving sights and sounds. Kathryn Bigelow, director of The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty directed a short documentary for National Geographic called The Protectors which shows the park from the point of view of the rangers who defend it. And, not specific to the park, Daniel McCabe’s documentary This is Congo showed me the M23 rebellion and the perspective of the Congolese army and the groups they were fighting.

What gave you the idea of using an expedition to search for the Northern White Rhinos, last seen in 2006, as the premise for an African adventure thriller?

This idea again arose from Last Chance to See, though not from the 1989 book, but from the 20th anniversary TV series. Sadly, Douglas had died by that time, but the BBC convinced the creature-comfort-loving Stephen Fry to take his place. The team attempted to travel to Garamba to see how the Northern White Rhino were doing 20 years after Douglas and Mark’s visit, but they could not. The rhino had already been declared Extinct in the Wild (EW), and besides, the park was judged so dangerous travelling to it was not possible.

I then read The Last Rhinos by Lawrence Anthony with Graham Spence. Lawrence was a South African conservationist who had been instrumental in rescuing animals from Baghdad zoo during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and whose book The Elephant Whisperer told the story of his rescue of a herd of elephants and slow development of a relationship with them. Lawrence learned of the plight of the Northern White Rhinos in Garamba, after the majority of them were slaughtered by poachers in 2003-2004, and he then attempted to have any survivors moved from Garamba to his conservancy, Thula Thula, in Zululand. It was the combinations of these two—ultimately unsuccessful—attempts to get to Garamba that led to my story.

Much of the action is experienced from the viewpoint of Colm Reid, a journalist on a small Irish newspaper. He doesn’t know what he’s letting himself in for, but he’s willing to take the risks for the opportunity of a great story. Why did you choose Colm as the main character, rather than your series characters Kennet and Jane Haven from their conservancy in Kenya?

In my first novel, Hunted, all the points of view we see the story through are from those experienced and familiar with their surroundings, which keeps the reader, who in the main will not be, a little distant from the action. For BORN THE SAME, I wanted to try something a little different, and to use Colm to reduce the distance between the reader and the action by making him unfamiliar with anything that is going on at all. I should say that the majority of my readers are from the UK, Australia, the US, and Canada.

There was a secondary attraction in using someone from Western Europe as a protagonist—to show the similarities between the plight of African large animals at the moment and the plight of European large animals over the last 30,000 years. In the novel, I use the example of the Irish Brown Bear, but in Yorkshire, 20 miles from my home, the bones of rhino, lynx, wolves, and bears have been found, some dying before the last ice age, but others, like the wolves and the bears, surviving until only a few hundred years ago. As human populations expand, animal populations contract.

And, thirdly, a former colleague of mine once said to me ‘if you ever need a slightly grumpy Irish character, use my name!’ Hopefully Colm Reid wasn’t joking…

The militias that poach in the national park and attack the rangers’ headquarters for the ivory stored there vary from ill-trained gangs to fairly efficient soldiers. They make their own rules in this part of the continent and fight over the spoils. How did you conceptualize the attack that split up of the visitors?

I wanted to unpick the word ‘poacher.’ At the simplest level, a poacher is a new word for someone whose ancestors did precisely what they are doing to survive, but at some point, governments were formed and applied a legal status to the animals those people feed on, changing them from ‘hunters’ to ‘poachers.’ Increasing numbers of people and fewer animals together create a problem with only one outcome if alternate livelihoods cannot be worked out.

At the other extreme, poachers are highly organised, heavily armed agents of international gangs who traffic rhino horn, elephant ivory, lion bones, pangolin scales, and many other animal parts. As wealth increases amongst the people who buy the items, and as there are fewer and fewer animals, the result is that the prices go up so the poachers are better armed and will take bigger risks. I have three groups of poachers in the novel, one at each extreme of this spectrum, and the third somewhere in the middle—opportunistic and disorganized, but motivated not by survival but by unimaginative greed.

Once I had established those groups, then the outcome almost fell into place by itself. If a group goes looking for something they have been told were killed by predators, then they should not be surprised if they meet the predators.

Colm seems out of his depth almost as soon as he reaches Garamba. On the other hand, Fatou Ba’s grandparents were born in the DRC and she has a DRC passport. Now a journalist in Belgium, she’s able to focus on the developing story. She also spots that there’s something strange about the Havens and their plans. Was her main role in the book to balance Colm’s inexperience of Africa?

Fatou definitely became that, though I created her in the first instance to give me an extra pair of eyes after a certain point in the story for dramatic reasons.

Fatou is less naïve than Colm, and more cynical. But she’s also grown up in a modern city, so certain things don’t occur to her—that she won’t be able to charge her mobile phone whenever she wants, for example. Her cynicism makes her a better journalist—Colm asks questions when he sees something that he doesn’t recognize or understand. Fatou makes assumptions that what she sees isn’t necessarily what she thinks she is seeing, and then asks questions.

She’s a quiet nod to hope. There are two Northern White Rhino alive in the world today. There is a project that is hoping to bring the species back from the brink of extinction by implanting Northern White Rhino embryos in Southern White Rhinos. The two living NWRs are called Najin, who is no longer able to donate eggs, and her daughter, Fatu.

A fascinating part of the story is the work and lives of the game rangers at Garamba. They are themselves a militia, having to fight off poachers and shoot or be shot. It’s amazing that there is still some type of protection for the animals in the area. Apparently, the situation in Garamba has recently improved. Would you comment?

The rangers of Garamba are incredible. All of the rangers in BORN THE SAME are invented, and I invented their compound and took some other geographical liberties in constructing their lives in the novel, but the characters are heavily inspired by the little I have seen and read of the real defenders of Garamba’s wildlife, without whom, it is quite possible there would be no megafauna left in the park at all—whilst the rhino are gone, the elephants, hippos, and especially the Congo giraffe, which is endemic to the park, still survive because of the Garamba rangers.

And yes, earlier this year, 16 Southern White Rhinos were relocated to the park, replacing the great wide-mouthed grazers who once walked through the grass. Hopefully this is the start of recovery, if not of the Northern White Rhinos in Garamba, of the ecosystem and the other animals in the park.

I gather that BORN THE SAME, a prequel to Hunted, interrupted the writing of Hunted’s sequel, which has already been short-listed for a prize. How did that happen, and when can we look forward to reading the sequel? Anything else in the pipeline?

I’ve struggled a little with getting Endangered right. The opening of an early draft was shortlisted for the First Pages award by the American Library of Paris back in January 2020. However, the structure of the story wasn’t quite right, and I left it on one side for a while as I wrote BORN THE SAME. Now that I am back writing Endangered, I’ve fixed what wasn’t quite right. Unfortunately, this has involved cutting the opening chapter that was shortlisted for the award. However, I think the new opening chapter is better.

I hope Endangered will be published sometime in the first half of next year.

I have a couple of other Jane Haven novels in development. Extinct, which will be the conclusion of the trilogy Hunted began, and an untitled piece that would slot into the timeline between BORN THE SAME and Hunted. I’m also working on a historical fiction novel set in Yorkshire, which is still very much at the ideas stage.

Learn more about Antony on Twitter at @antony_dunford or on his website.

The Big Thrill Interviews Antony Dunford

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024