Up Close: Karen Odden

Irish Need Not Apply

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

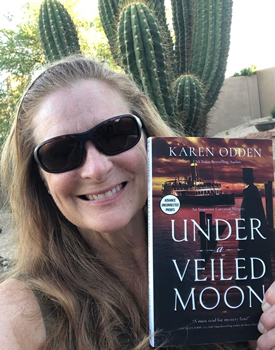

Inspector Michael Corravan is back in author Karen Odden’s Victorian mystery and second Inspector Corravan book, UNDER A VEILED MOON.

After solving the river murders while working for Scotland Yard the year before, Corravan is acting superintendent at Wapping River Police, not too far from the Irish district of Whitechapel, where he grew up.

When visiting Ma Doyle in Whitechapel—the woman who took him in as an orphan—Corravan discovers that someone is terrorizing the area, shooting people and looting stores. His adopted 19-year-old brother, Colin, has also fallen in with the wrong people—Corravan is worried that he’s working for an Irish crime boss named James McCabe, who runs the Cobbwaller gang. Corravan was once a member of a thieving gang, so he’s well aware of the danger involved.

There’s also a man’s murder to investigate.

Then the unthinkable happens. The coal carrier Bywell Castle rams into the pleasure steamer Princess Alice, sinking it and killing many of its more than 600 passengers. Working with his former Scotland Yard boss, Director Vincent, Corravan learns that all signs indicate the Irish caused the accident. Is it also related to the recent crash of a commuter train? And what does it have to do with the murdered man found nearby?

Corravan must investigate who caused the wreck and whether it was intentional, all while battling the rampant newspaper reporting that the crash resulted from the Irish waging war. Is there a plot to disrupt the moderate members of Parliament in restoring Irish Home Rule? Could there be such a profound hatred of the Irish to kill so many innocent people?

Odden’s expertise in Victorian London, including the social unrest and distrust of the police and Scotland Yard, gives readers a vivid depiction of life on the River Thames. Here, she chats with The Big Thrill about her motivation, how she wove the history of the Princess Alice sinking into her story, Victorian fake news, and racism against the Irish in 19th century England.

What was your inspiration for the story in UNDER A VEILED MOON?

The first inspiration was the profound and vicious racism I discovered as I was researching for Down a Dark River, and I knew I’d have to put it at the core of this book. My protagonist, Scotland Yard Inspector Michael Corravan, was born in County Armagh, Ireland, and raised in the Irish section of Whitechapel in the 1860s. Until I started digging, I didn’t understand how vitriolic the anti-Irish prejudice was in 1870s London.

Second, I was inspired by the historic event that is still known as “the worst maritime disaster in London.” On the moonlit evening of September 3, 1878, the pleasure steamer the Princess Alice was rounding Tripcock Point, a blind curve on the south shore of the Thames, when the 900-ton, iron-hulled coal carrier the Bywell Castle rammed into it, sinking the steamer within minutes and throwing all 630 passengers into the cold river. As the Princess Alice was one of a fleet of steamers—like our hop-on-hop-off tour buses—there was no passenger manifest, and no one knew who was on the boat. You can imagine the panic this caused.

How close is the narrative to the facts surrounding the sinking of the SS Princess Alice?

The events I’ve related about the collision are true, and I include many historical figures in my book, including Captain Thomas Harrison of the Bywell Castle and Frederick Boncy, the chief steward of the Princess Alice. Where I have departed from the facts is in the aftermath.

History tells us they found both ships to be at fault, for according to nautical laws, the two ships should have passed port side to port side, and they did not. Although it was the custom for smaller ships to hug the shore where the current was weaker, by law, the Princess Alice should not have been where she was, and the Bywell Castle was likely moving too fast.

However, the writer in me wondered, what if this wasn’t an accident? Who would want to cause a collision like this and why? Given the prevalent anti-Irish sentiment, I decided to explore what happens when early clues, reported in the newspapers, point to the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

The IRB (akin to the Fenians in the US) used violence to pressure Parliament into restoring Irish home rule, so a parliament that met in Dublin would govern Irish affairs, rather than the one that met in London. (Irish Parliament was dissolved in 1800 when Ireland joined England, Scotland, and Wales to become Great Britain.) Having early clues point to the IRB was a departure from the truth, but the IRB was real, as was the growing desire for Irish home rule.

Will you tell us more about the anti-Irish sentiment in England and how it correlates to the prejudice our 2022 world is experiencing now?

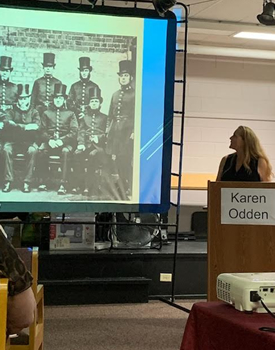

Odden gives a lecture titled “Victorian Mayhem, Murder, and Mystery” at McArthur Public Library in Biddeford, Maine.

Just to give you an idea of how systemic and accepted anti-Irish sentiment was, Benjamin Disraeli, who became the country’s prime minister and was a favorite of Queen Victoria, wrote in a letter to the London Times about the Irish “race”: “The Irish hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain, and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood.”

The brutality of Disraeli’s statement stunned me and made me dig further, and I discovered tropes, vocabulary and phrases, and essentialist claims based on supposed “scientific evidence” that sound a lot like what we find in anti-Semitic literature and in racist discourse today.

I also researched the role of newspapers in establishing attitudes in London. Victorian “social media” consisted of more than 1,000 newspapers in London by 1880, as well as handbills and other ephemera, and as we see today, many of them had a particular slant. I wanted to consider the role of repetition upon readers—what happens when the papers repeat a lie, the Victorian version of retweeting and reposting—to produce the effect of “truth” in people’s minds.

What does Corravan’s character represent in the context of the story?

On the one hand, Corravan is an outsider. He’s an Irish man in Scotland Yard, and the Metropolitan Police viewed the Yard with disdain and suspicion after four Yard inspectors were found guilty of taking bribes from con men in 1877. Just as Corravan had to strive to survive Whitechapel as a child, now he must strive to earn back public trust; once again, he is at a disadvantage.

But Corravan is also the everyman, trying to find the truth amid rumors and other people’s assumptions and agendas. Some of Corravan’s superiors push him to find a quick verdict, to take the “easy win,” declaring that the feared Irish Republican Brotherhood caused the collision. Some Irish friends are disgusted because Corravan didn’t immediately deny that the IRB had anything to do with it; they believe he’s kowtowing to English politicians, bending to systemic prejudice, and betraying his own identity.

Corravan has some personal skin in this game—especially when he discovers his younger brother, Colin, is enmeshed in the Cobbwallers, the Irish gang that runs gambling and protection in Whitechapel. But as my book suggests, we all have skin in this game. Racism and rumors and vitriol hurt everyone, inflicting wounds on our hearts that we rarely even perceive.

You’ve included very detailed descriptions of ships, docks, and traffic on the Thames in the novel. What did your research entail?

Last December I was in London visiting my daughter and went to the Museum of London Docklands, housed in a 19th century brick warehouse some ways east of central London. I saw lighter boats, dock scales and wooden swan-necked carts, a lighterman license like the one Corravan would have been required to carry, and maps of the Thames, the docks, and the developments over the years.

Many people don’t realize that the Thames is tidal, changing direction twice a day, for 100 miles inland, which is well past central London. The waters rise and fall up to 24 feet, which results in both trash and treasure being dumped on the shores for mudlarks to find. I also listened to oral histories and found books in the museum shop (I love museum shops!) that explained the history of the Thames from the Roman era onward and helped me understand what working on the docks would have been like for Corravan and what steering a ship on the Thames would have been like for the captains of the two ships that collided.

Fun factoid: In the late 1700s, West India merchants were losing as much as £500,000 (£4.5 billion in today’s money) every year from delays in offloading cargo and from theft, which led to a system of closed docks (so the ships didn’t have to moor randomly in the river, where thieves could pilfer by night) and to the founding of the River Police, the first organized police force in England in 1798.

Is there a message you’d like readers to take away from the book?

I never begin a book with a “message,” but the deep emotional theme comes to me as I write. This time, I had most of a first draft finished, and I still wasn’t sure what Corravan was supposed to be learning—his character arc. I knew it had something to do with mistakes and shame, but it wasn’t clear. And then, one night, my husband and I were talking about some missteps we’ve made, and he said ruefully, “Sometimes I wonder how we all live with the stupid shit we’ve done.” A bell went off in my head—because I realized that’s what Corravan is thinking.

When Corravan fled Whitechapel at age 18, he left Colin behind, and he didn’t look back because he was running for his life. But now, 13 years later, Corravan is faced with the effects of his leaving: Colin perceived it as abandonment, and it shapes Colin’s need to feel important and his misguided actions in the present. At first, Corravan is desperate to fix his mistake, to make amends. When he can’t, he feels a wave of shame and self-loathing. And then, at last, comes regret and a kindling awareness about how his actions affect others. His regret is painful, but he must live with it, so how can he turn it to some use?

So if there’s a message, it’s that regret is an important topic for discussion. How do we make peace with regret? How do we prevent getting locked in by shame, which often makes us “double down” on our mistakes? How do we teach our children that regret is painful but a natural part of learning?

Can you give us a hint about your next novel?

I’m hoping to be given the chance to write another Corravan novel. At the end of UNDER A VEILED MOON, Corravan receives a hint about what happened to his mother Saoirse, who vanished one day when he was 13. In Book Three, he learns the truth, in tandem with investigating a Yard mystery that involves a dead maid and a financial scheme surrounding the Suez Canal. I’m still in the initial research stages, but the history of the Suez is fascinating! This beginning research is always fun and surprising—I’m throwing pieces into the empty pot to start the stew.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND by Wanda M. Morris - June 27, 2024

- Sally Hepworth - May 10, 2024

- Katherine Ramsland - April 25, 2024