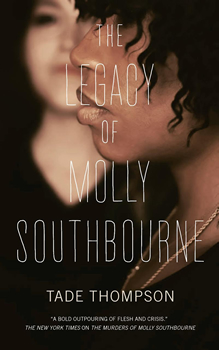

On the Cover: Tade Thompson

What Would You Do If You Met Your Doppelganger?

It happens to all of us at some point. We’re sitting in class, at a cocktail party, or lounging by the pool and someone asks, “What would you do if you met your doppelganger?” The answers range from the inappropriate to the illegal, but occasionally are as mundane as passing off chores we’d rather not be doing.

Molly Southbourne—the protagonist of Tade Thompson’s trilogy—would answer with something along the lines of, “I would kill her before she kills me.” You might consider this an extreme response, but Molly has plenty of experience dealing with her own clones: the mollies.

The mollies are not created in a lab, but instead grow from blood Molly sheds. They spring from the blood of a skinned knee, a tiny paper cut, an old scab ripping off—anything that makes her bleed. This is an awkward problem in its own right (imagine what the neighbors would say), but this problem is compounded tenfold when we learn that the clones’ first instinct is to kill Molly.

In the first book of the Molly Southbourne series, The Murders of Molly Southbourne, Molly walks us through her unusual life, a life frequently punctuated by violence—either during combat and survival training with her mother or defending herself from her seemingly mindless homicidal clones. We watch her grow up, go to college, fall in love, and begin discovering the truth of her unusual situation.

In Book Two, The Survival of Molly Southbourne, we are given the perspective of a molly with agency, who chooses to become her own person through a combination of her own interpretation of the memories of the original Molly, her lived experiences as clone-Molly, and the knowledge that she is a copy. We also meet another woman like Molly, Tamara, who lives in harmony with her clones and teaches clone-Molly how to begin to form non-homicidal relationships with the other surviving mollies. More of the history of the original Molly is revealed as a shady organization begins to hunt clone-Molly.

Now we are in Book Three, THE LEGACY OF MOLLY SOUTHBOURNE. Clone-Molly has chosen to take on the original Molly’s identity and has cautiously joined with three other mollies who have also developed their own names, personalities, and interests. They are, finally, individuals and a tentative collective, inspired by clone-Molly’s experience with Tamara in the previous book.

But this isn’t a peaceful story of four girls living their best lives in the English countryside, drinking wine with breakfast and braiding each other’s hair. Violence descends on the mollies as the original Molly Southbourne’s history catches up with them. Will they be able to come together to defend themselves from this new threat, or will their innate desire to kill each other destroy any chance of their survival?

The Big Thrill recently sat down with Thompson, who was kind enough to answer a range of questions about souls, doppelgangers, and trauma—without once asking us to calm down.

Within Western culture, we often equate souls with humanity or humanness. In effect, the possession of a soul is what makes us human. Within the world of Molly Southbourne, the copies often seem soulless. But there comes a moment when they are not—when they are human. What allowed this change?

Wow, there’s a lot here. So, there’s a problem of terms here. If we say the mollies are mindless, what is a mind? If we say they’re soulless, what is a soul? And whatever these definitions are, do only humans have souls? Do all humans have souls? When do humans acquire souls? At birth, or as they grow? Can humans lose their souls (for example, after catastrophic brain injury that ushers them into a persistent vegetative state)?

Right off the bat, you can see the difficulty. I blame Rene Descartes for the pervasive mind-body duality idea. I don’t subscribe to it.

The mollies aren’t mindless. They are newborns who have to learn but are tragically not given the time or opportunity before being executed. They are born with certain instincts, like you and I appear to be born with a demonstrable instinctive hatred/fear of snakes. The reason they perceive Molly Southbourne as a threat is revealed. Obviously, an existential threat needs to be neutralized without thinking if they are to survive, which is why their first instinct is to kill Molly Southbourne.

To answer your question more directly, time and learning allows the change.

Doppelgangers have been a trope in literature, art, and religion for centuries. They show up as changeling babies, as evil twins, as split personalities, as shadow selves—and with all of these, the fate of the original is inextricably linked to the fate of the double. What has drawn us so consistently toward this idea of the dark double? What, do you think, is the core of this fear and entrancement?

Part of it is the Jungian shadow self. We’d like to locate any undesirable traits outside ourselves, hence, “It wasn’t me. It was my evil twin.” In much of the extant folklore, the meeting with the double/fetch/wraith presages the death of the original; matter-antimatter annihilation if you will.

There are also many kinds of duplication. There’s the perceptual duplication of the self seen in autoscopy, there’s the idea that someone else has been duplicated (Capgras syndrome), there’s the idea of dissociative personalities.

Fragmenting off a part or whole of the person either physically or mentally is sometimes driven by traumatic experiences, for example. So, “This part of me has been hurt, but it is not me.”

It’s an interesting human phenomenon stretching from folklore to psychiatry.

If there is another reception of this idea in Nigerian folklore, could you speak on that and why you think there is a difference? I’m thinking specifically of the relationship between Tamara’s social cooperative versus Molly’s self-homicide.

Well, my forebears used to murder twins, so there’s probably something there in the origin of the narrative. It’s often said that the missionary Mary Slessor stopped this, but the practice was already in decline. The practice is rumored to continue among the Bassa Komo tribe, for example, by commission or omission (withholding feeding). The idea is that twins are demonic, blood suckers, and are destined to kill the parents. There are actual twin shelters right now.

Tamara’s attitude towards clones is contrasted with Molly’s ideas as a comparison of attitudes of individuality that predominate in the West, while cooperation and communalism predominate in Black African communities, although that has changed with cultural imperialism. Even the notion of selfhood is different, and one is seen as part of a group. Personhood isn’t achieved at birth.

Molly’s mother was a fighter who trained Molly to fight and destroy the mollies. The more fighting skills Molly learned, the more fighting skills the mollies themselves were born with. The skills weren’t the only thing inherited—Molly’s violent mindset was also passed on, meaning there was no opportunity for the mollies to be anything other than violent. When we compare that to Tamara, another woman with the ability to replicate herself, we find a different approach. Tamara’s mother raised her to accept the tamaras, which allowed her to create a collective of tamaras—a group of identical women working together for the common good. Was Molly’s approach to her copies intentionally speaking to intergenerational trauma? Was that something that you planned on putting into the stories or something that grew naturally?

It’s definitely about intergenerational trauma and generational memory. I also wanted to make a point about the origins of violence and nurturing, made explicit in the difference between Molly’s and Tamara’s reactions to a new clone.

This was always the idea. The community of clones was in my first draft of Murders, but my editor and I decided to remove it because it was extraneous in that volume.

Any further comments? Anything we missed?

I think it’s important to keep in mind that the root of this entire narrative is the idea of self versus self, a battle we must all fight each day of our lives. Because the self is contributed to by parents and the people you meet, it can sometimes be the self versus parents or strangers, but all interpersonal conflict might be a proxy war for us fighting our own selves.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024