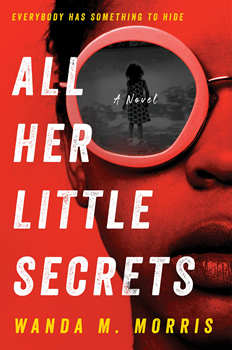

On the Cover: Wanda M. Morris

Overcoming Near-Insurmountable Tragedy

Wanda M. Morris is an accomplished lawyer, but ALL HER LITTLE SECRETS is her first foray into fiction—and what a splash she makes.

The novel centers around Ellice Littlejohn, a layered character that must confront the terrors of her past—all the dirty little secrets she kept from even her closest friends—and survive while trying to save her career.

Morris says that, despite the body count, this book is really about family—the family we choose and the family that chooses us. This is the story of a woman who overcomes nearly insurmountable tragedy to forge a new life and protect the people she loves.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Morris talks more about her debut and what readers can expect from her next.

Please tell us about the genesis of the story—what prompted it?

There were a couple things that inspired me to write this book. First, my own lived experiences working in toxic offices where management underestimated the value that women and people of color can bring to the workplace. Also, I once worked for an organization where company management considered its employees “family.” Someone in my department died unexpectedly. There was nothing sinister about the death, but I was mortified by how quickly everyone went back to normal after the person died. That incident stayed with me for a long time and served as the motivating idea for the theme of family that I explored in the book—specifically, who do we call family and why?

Tell us a bit about Ellice Littlejohn—how did you conjure her up?

Like all the women in the book, Ellice is an amalgam of women I’ve known or met in my life. Women who are smart, beautiful, strong, and hopelessly flawed. Ellice, for all her issues, is like a lot of real women in the world. She wears a mask of expensive clothes and educational pedigree to cover the residual pain and trauma from an earlier period in her life. It’s only when the layers of her mask are peeled away that she is finally free to be what she wanted to be all along—free and accepted for who she really is. Women in this society are stretched thin to be everything to everybody, and Black women in particular suffer the harshest rigors, whether it’s access to opportunity or economic parity with men. We are chastised for being too strong, “the angry Black woman,” but conversely, we tend to be the most disrespected and maligned. Who wouldn’t be angry? There is a moment in the book when Ellice returns to Chillicothe, and she looks around the town. She realizes who she is and what this town had made her—not an angry Black woman but a fighting Black woman yearning to be heard, respected, accepted, and protected.

Okay, I’ll step off my Black feminist soapbox for now. Next question!

What do you like most about Ellice Littlejohn?

One of the things that I like most about Ellice aside from her strength and love for her family is her strong sense of responsibility. In fact, it is one of the reasons she decides to accept the promotion, believing that by being in the executive suite she can bring about change to hire and promote more people of color.

Morris with Cheryl and Warren Lee, owners of the independent bookstore 44th and 3rd Booksellers in West End Atlanta

Like Ellice Littlejohn, I’ve been an advocate for women and people of color. I’ve worked as a vice president for diversity for an organization. In that role, I oversaw a myriad of initiatives including hiring and promoting people of color and other-abled employees. I also supervised supplier diversity and internal investigations into complaints of discrimination. While serving as the president of the Atlanta Chapter of the Association of Corporate Counsel, I founded the Women’s Initiative, a mentoring and empowerment program for female lawyers working inside corporations. In my capacity as a corporate employment lawyer, I’ve helped to resolve a multitude of claims to ensure a fair and equitable workplace. I think I’ve been fighting some sort of fight for the disenfranchised for the bulk of my legal career.

Personally, I feel a responsibility to pay back all the women before me like my mother, my grandmothers, and every other woman who was oppressed and disenfranchised but still got up each day and worked hard so that I can enjoy a life they never knew was possible for them.

And if we’re smart and stay the progress we’ve made so far, my daughter and granddaughters won’t see a return to those days of our female ancestors. Read the book and you’ll know what I’m talking about!

In the opening of the book, Ellice discovers her lover’s body in his office, yet she backs away and doesn’t call the police. Can you explain why she acted that way?

Morris with her husband, Anthony Hightower. “He is my rock,” Morris says. “I wouldn’t be able to do this writing journey without his support.”

You have to understand a couple things. First, not everyone has the same experience or perspective with law enforcement. Ellice’s experience with law enforcement was colored by her childhood. Many people in communities of color have a mistrust of the police for varied and justifiable reasons. Ellice is no different.

Second, you have to understand the psychology of trauma. Trauma can make people who are otherwise intelligent and responsible act or behave in an unusual manner. What may seem like a perfectly logical way to behave to some may seem like an unraveling to someone who’s lived with trauma. I caution people not to be so quick to judge. You don’t know what someone is living with. Because of Ellice’s childhood, her “go to” instinct at the first sign of trouble is to run. Calling the police after stepping inside that executive suite, with all the secrets she had, was not her first choice.

Lana and Grace—one would bring a casserole while the other would bring body bags and shovels. Even the minor characters seem real. How do you do that?

I like characters that feel real to me, even minor characters. To do this, I try to write minor characters that have a dynamic interaction with the main character. For example, there is the nursing home aide who helps Vera and gives Ellice an understanding nod when Vera has a meltdown. Even the minor characters have some connection to what the protagonist is dealing with in the story. Or the Black hostess who works in the executive dining room. She and Ellice share a wink because they are the only two Blacks on the 20th floor, and they understand what that means. Interestingly, nearly every woman in the book is on a personal journey of sorts. Whether it’s Grace dealing with the strictures of her marriage or Willow, Ellice’s white female colleague on the 20th floor, also trying to maneuver her own journey in the executive suite.

Tell us about the differences between the New vs. Old South? How much has changed and what has remained the same (even if under a different name)?

Certainly, there’s been some progress made. We aren’t using separate facilities or riding in the back of buses anymore. But the same systemic oppression we dealt with in the Old South still exist in this “New” South. Specifically, things like the wealth gap between Blacks and whites and the obstacles to upward mobility into the executive echelons of the Old South still exist. The same unfair legal system that prosecutes Blacks at far higher numbers than whites still exist. Right now, in the state of Georgia, recently enacted laws make it tougher to vote in this state than it has been in decades. I could go on. There is still much work to be done.

On that same vein, can we talk a little about racism in the current work environment?

Morris at home, on a staircase lined with pictures of “‘the ancestors,’ relatives that I aspire to in strength and hope to make proud”

I think it’s something a lot of Black women struggle with. As a Black woman, there are constant reminders of your “otherness” from the time you walk into a room and count the number of other Black people in the room, to the awkward stares you get when you switch up your hair, to the butchering of the pronunciation of your name. I may be wrong, but I doubt that my white male colleagues do those kinds of assessments—counting up the number of other white males when they enter the executive suite.

But still, you feel a responsibility to stay in the room, to sit at the table. You feel responsible for every other Black person or woman who can come along behind you. For me, as an attorney, I think to myself, I paid for my law degree just like all the others in the conference room or the corporate jet or the whatever white space I happen to be in. I deserve to be here. I always think, maybe my presence here will send the message that we all belong, including other people who look like me.

It’s particularly egregious in the executive suite where only three percent of executive management in Fortune 500 are Black. That’s an incredibly small number. It’s particularly sad when you think that so much of a company’s initiatives and policies are driven from the top down. People in the executive suite make the decisions and make it possible for others to make decisions. When the executive suite is homogeneous, you get homogeneous thinking out of it. And that’s not good for the bottom line of any company.

Throughout the book, Ellice has had to learn to manage predominantly white spaces—from boarding school to the boarding room. It’s another unfortunate layer of anxiety of managing life as a successful Black woman.

- Mark Greaney by José H. Bográn (VIDEO) - June 27, 2024

- Brian Andrews & Jeffrey Wilson by José H. Bográn (Video) - May 23, 2024

- Classic Thrills: THE DAY OF THE JACKAL by Frederick Forsyth - May 10, 2024