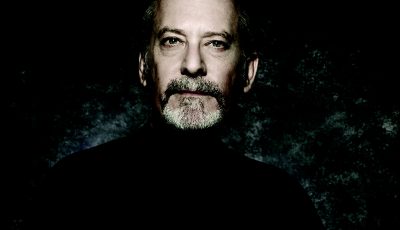

Up Close: Jonathan Kellerman

Slithering Back into Your TBR

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

Jonathan Kellerman is accustomed to digging into the roots of evil. It’s often the motivating drive behind his writing—telling the stories that illuminate human behavior at its best. . . and worst.

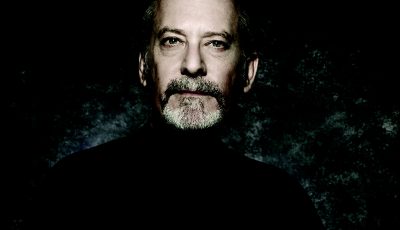

The “vehicle” for most of those stories is Alex Delaware, a forensic psychologist and consultant for the Los Angeles Police Department—and the recurring protagonist in 36 of Kellerman’s thrillers, the most recent, SERPENTINE, releasing this month.

Kellerman, a renowned psychologist, makes no bones about the themes that inspire his bestselling novels—or why he thinks his fans have stuck around for each series installment.

“These are timeless themes,” he says. “I’d like to think that same appeal applies to a certain type of reader: intellectually curious and fascinated by the whydunit as well as the whodunit.”

In the aptly-named SERPENTINE, the answer to both of those questions takes several twists and turns before its climactic end. Kellerman, who says he is “always trying to challenge himself,” begins this novel with a seemingly “unsolvable murder.”

It’s a brutal, decades-old cold case that Delaware’s best friend, LAPD Detective Milo Sturgis, can’t solve on his own—but is under tremendous pressure from the department to do so quickly. The “client” is a wealthy, demanding mogul obsessed with the death of her mother—a woman she never knew, who has been dead for decades.

There is no motive. No evidence. No witnesses. Not to mention the fact that Milo and Alex aren’t the first to work this case—past detectives have failed. And, as Kellerman’s fans already know, failure is not an option for Milo. He has a near-perfect solve rate, and no way does he plan to let this case set a different precedent.

Since the series’ debut in 1985 with When the Bough Breaks, Kellerman has put Delaware through the paces. But over the years, he’s been joined by a number of important characters, perhaps none more significant than Milo Sturgis. Their bond continues to deepen in SERPENTINE.

“Each book—the characters, the story—dictates how the two of them function and interact,” Kellerman says. “I suppose some of them can be thought of as ‘Alex books,’ others as ‘Milo books,’ but I never set out to divide up center stage. Similarly, I don’t set out to ‘arc’ their relationship. Whatever changes occur are organic—engendered by the story. The two of them are real to me. They live in my head and seem to do exactly what they want to do.”

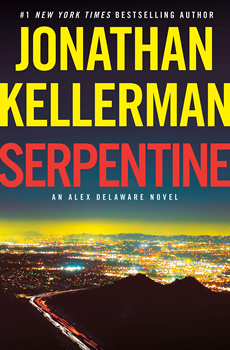

Kellerman and James Ellroy during the release of Ellroy’s 1987 novel The Black Dahlia, which Kellerman has described as a masterpiece. Photo credit: Craig Graham.

In SERPENTINE, they do a lot of digging. What they find are too many coincidences, more “fabrication” than “fact,” and a new, very real threat that lurks in the present. The story moves at breakneck pace, reaffirming Kellerman’s status as one of the best in the genre.

“For some reason, I’ve never grown bored with Alex or Milo, nor with writing,” he says. “This is the best job in the world, and I deeply appreciate the support of loyal fans who enable me to pursue it.”

It might be hard to believe now, given the millions of copies of his books sold, but Kellerman didn’t land upon his dream job easily. Like many aspiring writers, he once had a drawerful of unpublishable manuscripts. Perseverance is important, sure, but Kellerman says there are a few other factors to consider if you’re looking to make writing a viable career.

Jonathan, Faye, and Jesse Kellerman celebrate Jonathan’s mom’s 100th birthday. (She turned 101 on January 27th.) Photo credit: Terri Porras.

“I got published because I got good enough,” he says. “It took a lot of false starts, acquiring more life experience and learning to take the construction of a novel seriously as a job, not just personal exploration. My primary advice is don’t do it unless you really love it.”

Sounds logical. But wait, there’s more.

“Also it’s important to achieve balance between self-evaluation and self-excoriation. In other words, appreciate that your words aren’t sacred and that few writers don’t profit from rewriting. But don’t allow the opinions of others—especially unpublished others—to erode your self-esteem. It’s a strange equilibrium, vacillating between ‘I’m a genius!’ and ‘Time to cast a cold eye on some of that stuff I wrote when I convinced myself I was a genius.’’’

When it comes to that evaluation, Kellerman admits to having a bit of an advantage—his “equilibrium balancers” are close to his heart. His wife is bestselling author Faye Kellerman—interviewed in last month’s The Big Thrill—and two of their children are also published authors.

“It’s definitely helped as we understand each other on a whole different level,” Kellerman says. “Faye and I have been married nearly 50 years and recently, while discussing the limitations imposed by the pandemic, she smiled and said, ‘Honey, I could do this with you for years.’ We’re incredibly lucky to have such a lovely relationship and as Faye says, ‘No jealousy. It all goes in the same bank account.’”

Also an accomplished musician and the author of With Strings Attached: The Art and Beauty of Vintage Guitars, Kellerman owns a collection of more than 120 guitars, mandolins, and other stringed instruments. Photo credit: Terri Porras.

Success, it would seem, is hardwired into their family genetics. The Kellermans’ son, Jesse, was a bestselling author before he and Jonathan started collaborating—their most recent co-authored book, Half Moon Bay, came out in 2018—their daughter Liza is a published author who makes her living in the world of technology and finance, and daughters Rachel and Ilana are clinical psychologists.

Life, Kellerman admits, is pretty good—despite the challenges of the past year.

“I wish everyone good health and shared optimism that this rather bizarre period in our collective lives will pass and that we can stop using that repellent phrase, ‘The New Normal.’ I want ‘The Old Normal.’ If my books have helped you get through this, I’m thrilled.”

As for Kellerman, he’s getting through the best way he knows how—writing more (and more) books.

“One positive aspect of COVID—I grasp for such—is that the enforced isolation has led to bursts of creativity,” he says. “I’ve completed next year’s Delaware, City of the Dead, and am about half-way through the novel after that, titled Unnatural History. When I’m not writing, I’m painting, working out in the home gym, attending to our menagerie (birds, fish, turtles, genius dog), and humbling myself playing classical guitar, OUD, and Viola da Gamba.”

- On the Cover: Alisa Lynn Valdés - March 31, 2023

- On the Cover: Melissa Cassera - March 31, 2023

- Behind the Scenes: From Book to Netflix - March 31, 2023