ICONS: John le Carré

Master of the Espionage Thriller

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

It’s no secret as to why John le Carré’s espionage fiction resonates with so many readers—the former spy-turned-novelist knew that deep down, we all want to be spies.

Le Carré—a pen name for David Cornwell—once served in Great Britain’s intelligence agencies M15 and M16, and perhaps ironically delighted in maintaining secrecy in his own personal life, refusing for many years to even acknowledge that he’d been a spy himself.

He began his writing career in the early ’60s, with two mysteries featuring British spy George Smiley. But it was his third novel—The Spy Who Came in from the Cold—that truly cemented his reputation and allowed him to leave the spy business behind—at least off the page.

Often described as the antidote to James Bond, le Carré’s novels stripped away the glamor and romance, instead focusing on the dark and seedy life of the professional spy. In the twilight world of le Carré’s characters, the distinction between good and bad, right and wrong, always hovered in shades of gray.

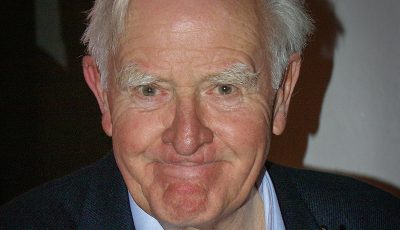

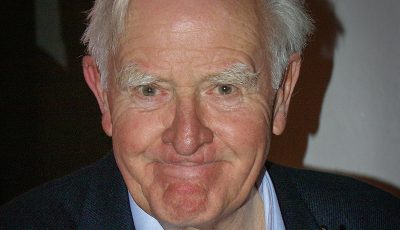

Le Carré signs books after a ceremony at the German Embassy London in June 2017. Photo credit: German Embassy London, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license, via Wikimedia Commons.

Most of le Carré’s novels took place during the Cold War and brimmed with an authenticity assisted, in part, by his real-life experience, but fueled by his passion for telling great stories. The books took readers deep into “the Circus” with jargon such as “honey trap,” “mole,” and “lamplighter” becoming common verbiage for all novels of espionage. It’s no wonder his work has become so imbedded in pop culture.

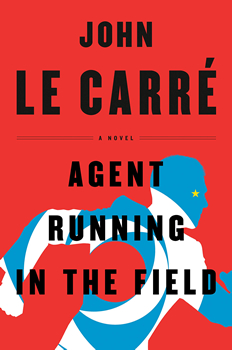

In 2019, le Carré published his 25th novel, Agent Running in the Field. Sadly, it would be his last. Le Carré died on December 12, 2020, at the age of 89, after a short bout of pneumonia. He was a literary giant and a humanitarian—and will be deeply missed.

Le Carré gives a keynote speech at the German Embassy London in June 2017. Photo credit: German Embassy London, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license, via Wikimedia Commons.

The gap left in the literary world following le Carré’s passing is difficult to put into words—it’s unlikely anyone will ever fill it. But here, five authors who have been impacted by his work try to quantify what his books meant to the genre—and to them. Please welcome Gayle Lynds, whose bestselling novels paved critical inroads for female authors in a traditionally male-oriented genre; Paul Vidich, an award-winning author of espionage fiction; K. J. Howe, the author of the captivating Thea Paris kidnap-and-ransom books; New York Times bestselling author Christopher Reich; and Jack Arbor, the author of six thrillers featuring wayward KGB assassin Max Austin.

What was your first encounter with John le Carré’s work, and what was your response to what you read?

Paul Vidich: I read John le Carré’s third novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, in my 20s, and it had an hypnotic effect on me. I read it about 15 years after it was first published in 1963—two years after the erection of the Berlin Wall—and it still had the dark urgency that had made it an international bestseller when it was released. The world he created was so real, so true, so compelling that it stayed with me long after I put the book down. The grim story, its empathetic characters, the clever plot, and the masterful writing changed my way of looking at spy novels.

Le Carré at the Zeit Forum Kultur in Hamburg in November 2008 Photo credit: Krimidoedel, distributed under a CC BY 3.0 license, via Wikimedia Commons.

K. J. Howe: Growing up, my father worked in telecommunications so I moved from place to place, living in the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean. Books became a wonderful escape and the international spy thriller was my absolute favorite thriller subgenre. I was captivated by le Carré’s tales of intrigue and lived vicariously through them.

Christopher Reich: The Honourable Schoolboy. I was in college and found it dull and impenetrable!

Jack Arbor: It was 2001 and I was living in India and had just finished E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. I grew fascinated with the British Empire, and to pass the stifling summer months, I read as much as I could about British imperialism. This led me to an interest in British authors, and of course le Carré’s fiction—most notably The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Coincidentally, that miserably hot summer in New Delhi is the first time I attempted, and failed, to write fiction. While le Carré was not the direct impetus for my desire to write—that was Ken Follett’s Eye of the Needle—le Carré’s portrayal of nuanced human nature taught me that characters are not black and white and instead are beset by emotional conflicts where the answer is rarely clear. This ambiguity of moral compass directly influences my writing today.

What are some of the defining characteristics of le Carré’s brand of espionage?

PV: Le Carré’s characters are ordinary men and women who reluctantly take on dangerous work, and always with a keen sense that things might not be as they seem. His spies are married, keep mistresses, suborn friends, see through the deceptions of lazy bosses waiting to retire, and they are men who struggle with faith and faithlessness. They may disagree with orders, but they rise to duty because it is what is required of them, and they endure regrets. Le Carré’s novels have the tropes of all spy novels—silenced pistols, suspense, footsteps in the fog—but his characters’ conflicts hinge on delicate lies and ambivalent moral choices. He isn’t the first spy novelist to offer up gritty cynicism—Eric Ambler and Graham Greene did it before him—but le Carré’s novels are subtler and more subversive.

And there is another defining characteristic. His novels are extraordinarily well written. Le Carré cared about writing and had a monastic devotion to his craft. Two contemporary writers, Joseph Kanon and Ian McEwan, put le Carré among the greatest English-speaking writers of the last half of the twentieth century. I concur.

KH: Authenticity and verisimilitude are the immediate characteristics that come to mind. George Smiley is not a glamorous Bond-like agent, but rather an understated, realistic version of a spy as he is often described as short, balding, middle-aged. The fascinating tradecraft and masterful plotting are le Carré’s trademarks. He had an amazing ability to show how the mundane plodding of spy work results in profound consequences.

CR: A man-on-the-street view of the guts and inner workings of the intelligence game. Nothing glamorous here. The piecemeal work of spies and their masters, both of whom usually suffer unpleasant consequences as a result of their allegiance to a spotty cause.

JA: Despite le Carré’s satiric depiction of the British Secret Service as the Circus, his stories were often defined by realism, authenticity, and moral vagaries. As juxtaposed to Ian Fleming’s writing—which portrayed a stark gulf between right and wrong, West versus East, good against evil—le Carré put characters (and institutions) in situations where their choice is often defined by moral tradeoffs. He also took great pains to show espionage as psychological head games played by men and women mired in bureaucracies instead of action-packed romps through the countryside. I think le Carré would argue that real spy games are a result of human desires, needs, wants, and the nuances of emotion rather than the logical output of a carefully crafted mission to triumph good over evil.

Le Carré’s body of work is some of the most recognized in the literary world—why do you think readers responded so strongly to his work?

PV: Le Carré understood that spies are ideal subjects for fiction. Spies lie for a living. We all lie a little in our lives, but the spy’s life is about deception and betrayal, and it is often done for a higher purpose. He understood that a spy story is not just a spy story, but can be a love story, a story about engagement and escape, a tale about the search for integrity or revenge. Spies marry, cheat, divorce, play games of sexual and political betrayal, and all this plays out with high stakes, which makes his work entertaining. We read his novels for his stories and we reread them for his writing.

KH: Le Carré’s career spanned over 60 years, and to remain a literary giant for such an extended time speaks to his unparalleled talent. His books are gritty, realistic, raw—often extrapolated from his real-life experiences. He offers critical insight into the life of a spy, not glamorizing it, but rather demonstrating that much of the work was mundane and morally bankrupt. Engaging in betrayal and sowing disinformation is part of a spy’s everyday life, and the characters are painted in various shades of gray. In his books, the deep reflection of what it means to be human is a key factor in what makes him one of the all-time greats.

CR: First and foremost because he tells a good story. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is one of the most ingenious tales ever thought up. Talk about a twist! Second, because his characters are so real.

JA: One of fiction’s roles is to help readers make sense of the world. Le Carré’s early stories, which were steeped in the Cold War and written by a Cold War spy, did just that. While readers flocked to Ian Fleming’s escapism, le Carré’s writing gave readers a vehicle to attempt an understanding of the chaotic events around them and in the news. Readers also responded to the realism of le Carré’s characterizations—they see a little bit of themselves in George Smiley, who endures his wife’s indiscretions for what we believe is true love. While readers fantasize about being James Bond, they empathize with George Smiley.

How great would you say le Carré’s influence is on today’s espionage and spy fiction?

Gayle Lynds: We walk in the footsteps of giants, we authors of espionage novels, and le Carré dominates, beginning with his first one, Call for the Dead (not The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, which was his third book). By using realistic spycraft, actual political situations, and infusing his heroes with painful moral and ethical dilemmas even when they’re winning, especially when they’re winning, he created a world of secrets and power that is perennially seductive. Since then, the job of those of us in the field has been to bring fresh ideas and novel uses of those basics to our books.

PV: Graham Greene called The Spy Who Came in from the Cold “The best spy story I have ever read.” He said this in a blurb, and unlike most blurbs, the hyperbole happens to be justified. Alec Leamas reaching down from the Wall for his fallen girlfriend in the novel’s last scene survives as one of the Cold War’s iconic images. You can’t write Cold War spy fiction without being touched by, or influenced by someone who was touched by Spy. The international success of Spy established le Carré’s reputation, but his later books, particularly the Smiley trilogy, cemented it.

KH: His influence is unmeasurable and unparalleled. Le Carré’s books stand out because of the quality writing, the in-depth research, the brilliantly crafted spy plots, and let’s not forget the unforgettable love stories, like the one showcased in The Honourable Schoolboy. When the Cold War warmed, le Carré shifted gears seamlessly, delving into other fascinating worlds, like Big Pharma in The Constant Gardener. Directly or indirectly, most international thrillers written today bear evidence of his fingerprints on them.

CR: Le Carré turned espionage-themed literature on its ear by writing stories that read more like “true crime” than a fantastical thriller. It’s said he was the antidote to Ian Fleming.

JA: One of le Carré’s biggest influences over today’s fiction is in the presentation of a balanced view of the sides to a conflict, whether person-to-person or culture-to-culture. Every villain’s actions are based in the human condition or a belief system that they hold to be just. Protagonists and antagonists each act from a set of emotions, wants, and needs, where the lines of right and wrong are often blurred. In le Carré’s The Little Drummer Girl, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is depicted in a balanced story that illuminates the human sides of the conflict. This style of balanced portrayal is pervasive in today’s stories, including the television series Homeland and Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon series. Le Carré shows us that there are humans on both sides of conflict, a lesson perhaps especially poignant in today’s world.

JA: One of le Carré’s biggest influences over today’s fiction is in the presentation of a balanced view of the sides to a conflict, whether person-to-person or culture-to-culture. Every villain’s actions are based in the human condition or a belief system that they hold to be just. Protagonists and antagonists each act from a set of emotions, wants, and needs, where the lines of right and wrong are often blurred. In le Carré’s The Little Drummer Girl, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is depicted in a balanced story that illuminates the human sides of the conflict. This style of balanced portrayal is pervasive in today’s stories, including the television series Homeland and Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon series. Le Carré shows us that there are humans on both sides of conflict, a lesson perhaps especially poignant in today’s world.

Did his work influence your writing, and if so, how?

GL: One of le Carré’s strengths was his use of place as character. I remembered that as I was struggling with the story of an idealistic CIA recruit I’d pitted against a cynical veteran as they walked undercover through Old Vienna to a meet. But I needed more for the story, a third “character.” So I turned to the city, spy central in those days, which gave me my ending. In a lovely payoff to my homage, British actors read my story, “Max Is Calling,” on BBC Radio4 in 2011 as part of their celebration of John le Carré’s 80th birthday.

PV: When I was writing my first novel, An Honorable Man, I struggled to find a voice for my main character, George Mueller. The book, inspired by the case of my uncle, Frank Olson, who was murdered in 1953 while working for the CIA, explores the dark side of Cold War spying. Olson had doubts about his work and wanted to get out of the agency, but he was a man who knew too much, and he couldn’t simply leave. I wrote the book three different ways, but each version suffered because I was too close to the story. I set the novel aside and then returned to it a few years later. I found the right voice by listening to the voices in le Carré’s work. I am indebted to him for that.

PV: When I was writing my first novel, An Honorable Man, I struggled to find a voice for my main character, George Mueller. The book, inspired by the case of my uncle, Frank Olson, who was murdered in 1953 while working for the CIA, explores the dark side of Cold War spying. Olson had doubts about his work and wanted to get out of the agency, but he was a man who knew too much, and he couldn’t simply leave. I wrote the book three different ways, but each version suffered because I was too close to the story. I set the novel aside and then returned to it a few years later. I found the right voice by listening to the voices in le Carré’s work. I am indebted to him for that.

KH: Absolutely. Le Carré’s novels had an overarching theme of betrayal, and that’s a profoundly painful experience that touches us all—can we really trust anyone, especially those who are closest to us? I often include betrayal in my novels because it ramps up the emotional power of a story. Who doesn’t get riled up when someone we trust stabs us in the back? Those moments can ratchet up the reader’s engagement, providing a dynamic roller coaster ride.

Like le Carré, I’m passionate about international locales, bringing all the sights, sounds, and tastes of a particular setting to readers, transporting them to an unfamiliar and interesting world. I’ve just finished a new book called The Perfect Hostage which takes place in the backdrop of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict—sadly, the 1983 The Little Drummer Girl’s similar conflict is still relevant today.

Like le Carré, I’m passionate about international locales, bringing all the sights, sounds, and tastes of a particular setting to readers, transporting them to an unfamiliar and interesting world. I’ve just finished a new book called The Perfect Hostage which takes place in the backdrop of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict—sadly, the 1983 The Little Drummer Girl’s similar conflict is still relevant today.

I also strive to bring authenticity to my novels via extensive research. When I read, I love to be entertained and educated. Most importantly, le Carré exposed human frailties in a realistic and captivating way, exploring character from different perspectives, and his flawed characters were his greatest triumph.

CR: Obliquely. I learned that I couldn’t write like him and in doing so, found my own voice.

JA: I’d argue that le Carré’s work helped crystalize the techniques used to bring to life the sympathetic antihero. To me, there is no more fascinating character sketch than humanizing the antagonist or writing a likable character who may otherwise embody counter-culture or counter-morals. Take assassin stories, a genre characterized by this moral ambiguity. How do we root for a hero who kills for a living? Killers are people too, and sympathy can be achieved through context and humanization. An exploration of why they kill, how they kill, and perhaps by exploiting a sliver of a voyeuristic admiration. George Smiley, le Carré’s protagonist, appreciates Karla, his KGB antagonist, as a worthy adversary, and takes Karla’s eventual death as hard as that of a family member. While we root for George in his cat-and-mouse games against Karla, we are almost as sad as George is when the battle is over because of the admiration we feel for Karla through George. The humanization of the antihero is central to my stories, and le Carré’s writing pushes me to mine the depths of the human condition for nuggets of emotion and empathy.

JA: I’d argue that le Carré’s work helped crystalize the techniques used to bring to life the sympathetic antihero. To me, there is no more fascinating character sketch than humanizing the antagonist or writing a likable character who may otherwise embody counter-culture or counter-morals. Take assassin stories, a genre characterized by this moral ambiguity. How do we root for a hero who kills for a living? Killers are people too, and sympathy can be achieved through context and humanization. An exploration of why they kill, how they kill, and perhaps by exploiting a sliver of a voyeuristic admiration. George Smiley, le Carré’s protagonist, appreciates Karla, his KGB antagonist, as a worthy adversary, and takes Karla’s eventual death as hard as that of a family member. While we root for George in his cat-and-mouse games against Karla, we are almost as sad as George is when the battle is over because of the admiration we feel for Karla through George. The humanization of the antihero is central to my stories, and le Carré’s writing pushes me to mine the depths of the human condition for nuggets of emotion and empathy.

What do you think is the most important contribution le Carré gave to the literary world?

PV: Le Carré’s distinction and originality is that he used the conventions of the spy novel for the purposes of social criticism. The British intelligence bureaucracy and the men in it (and they are largely men) represent the social attitudes and vanities of a certain class of Englishmen. Le Carré used espionage as Conrad used the sea and Kipling India, as an exotic world in which to explore the inconvenient truths that exist in a democracy that finds it hard to balance openness with the need to keep secrets. He stayed within the guardrails of the spy genre, but his work transcends genre.

KH: Nuanced, subtle—le Carré had an ability to expose the human condition like very few other authors. In his novel, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, his brilliant writing makes it difficult to tell the good guys from the bad. The search for a mole exposes the fact that no one lives free of sin or blame.

KH: Nuanced, subtle—le Carré had an ability to expose the human condition like very few other authors. In his novel, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, his brilliant writing makes it difficult to tell the good guys from the bad. The search for a mole exposes the fact that no one lives free of sin or blame.

CR: George Smiley.

JA: The list is long, but I’d argue le Carré’s most important contribution is his emphasis on realism. He reminded us to look askance at world institutions and leaders, and to seek truth among the kaleidoscope of white lies and half-truths. To le Carré, the Cold War and the Gulf War were examples where truth was manipulated for the gain of powerful men, where the public was led to believe propaganda in order to achieve a morally questionable outcome. Le Carré in life and in his writing was an unapologetic realist who portrayed the world through the lens of principle and sometimes a lens of satirical cynicism designed to elicit truth. Le Carré’s passing is perhaps even more tragic today for it robbed us of an advocate for truth, which some may argue, is more sorely needed now than during the Cold War.

- On the Cover: Alisa Lynn Valdés - March 31, 2023

- On the Cover: Melissa Cassera - March 31, 2023

- Behind the Scenes: From Book to Netflix - March 31, 2023