Up Close: Judy Melinek and T.J. Mitchell

Forensic Pathology at Its Finest

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

In AFTERSHOCK, bestselling author duo Judy Melinek and T. J. Mitchell return to the San Francisco Medical Examiner’s office with Dr. Jessie Teska, who is battling the aftermath of a devastating earthquake while investigating murder.

Jessie moved from Los Angeles to the San Francisco Medical Examiner’s office for a new start after her life unraveled. Although she’s now the deputy chief, she’s pragmatic—living in a tiny converted cable car named Mahoney Brothers #45 with Bea, her Beagle. The only extravagance she’s allowed herself is her BMW 235i—she spends most of her paychecks on her massive student loan debt.

When Jessie’s phone plays the ringtone “Don’t Fear the Reaper” in the middle of the night, she knows it’s a call from her office—someone has been killed, crushed at the construction site of the new SoMa Center. But upon autopsy, Jessie determines that the accident was a coverup for murder and begins her investigation. And complicating matters, a catastrophic earthquake strikes San Francisco—not only obliterating the crime scene, but also injuring Jessie.

Jessie must use clues from her autopsies to track down the killer. Because she’s skilled at putting her foot in her mouth, amid cursing in Polish, Jessie stirs the pot of potential suspects. Someone is getting nervous, and that someone wants her silenced. With help from her bounty hunter friend, Sparkle, Jessie stays one step ahead of the danger that surrounds her. But can she identify the murderer before someone stops her?

With Melinek an experienced medical examiner, she and Mitchell not only pack Jessie’s story with the intricacies of the autopsy at the center of the story, but also delve into other cases that come into the morgue. Fans of forensic science mixed with the thrill of the chase will love Jessie and her mission to allow the dead to tell their secrets.

Here, Melinek and Mitchell speak with The Big Thrill about what it’s like to be a forensic pathologist and how they incorporate real-life experiences into their stories.

How much of a parallel is there between Melinek and Jessie Teska? Does Melinek speak (and curse) in Polish?

Neither of us speaks Polish, apart from a handful of food terms and everyday phrases, though we both grew up hearing the language from the old folks at home. When we first started writing the series, we knew we needed to create a protagonist who was steeped in the American immigrant experience because that experience is essential to who we are. Judy is an immigrant to the US from Israel, and her first language is Hebrew; T. J.’s parents are first-and second-generation Americans with roots in Ireland, Italy, and Poland. The Polish language is part of our shared heritage—Jessie’s mother’s jak się masz, kociątko? (what’s new, pussycat?) is something Judy’s Polish-born grandmother used to say all the time—and so came the birth of Czesława “Jessie” Teska.

What do each of you bring to the writing process?

There is a little bit of both of us in Dr. Teska. Like Jessie, Judy often finds she has no filter and speaks before she thinks. T. J. comes from the North Shore of Massachusetts, and Jessie’s Boston diction and New Englander’s worldview is baked deep into his character. Jessie is our recalcitrant child, a combination of character traits we each have but don’t share. People ask us how we, as married coauthors, can work together to invent murders without committing any in the process. The answer is that we have no overlapping skill set. Judy has the experience and imagination to provide the story structure and investigative tactics, and T. J. is one of those writers who loves being locked in a room wrestling with adjectives all day.

Melinek, a prominent, board-certified forensic pathologist whose areas of expertise include wound interpretation and gunshot wound trajectory, brandishes a tool of the trade.

What is the most gruesome case Melinek has ever worked?

In AFTERSHOCK, there is a description of a badly decomposed human body. We tried not to be macabre in writing this part of the story, but that scene does come from Judy’s actual experience. It’s pretty rough. You get used to decomp—even so, a bad stinker will ruin your day for real.

That’s not the toughest part of the job for a forensic pathologist, though. The toughest part is in quantifying pain and suffering. There’s no diagnostic test for pain. It’s part of a forensic pathologist’s professional expertise to analyze what has caused someone’s death and to describe that experience to laypeople. This is particularly important in a jury setting: pain and suffering are determining factors in both civil and criminal cases involving death and injury, especially in the penalty phase.

In our first book, the nonfiction Working Stiff, we tell the story of one of the worst cases Judy has ever seen. The reason we included it in that book was to reflect this role she and her colleagues play in real life legal settings. In our fiction, we would be unlikely to incorporate anything so nightmarish. We’re more interested in the human circumstances surrounding the fictional deaths we create than in exploring the more lurid things that Judy has seen on her morgue table.

Did Melinek work at the old SF Medical Examiner’s office before the new building?

She sure did! We take all of that morgue detail from her authentic experience, practically documentary. The old Medical Examiner’s Office at the Hall of Justice in San Francisco was a museum piece. It had been in operation for 50-plus years. The tables were porcelain—like a toilet, complete with a foot-pedal flushing mechanism to clear them of leftover human remains between cases. There were glass specimen jars, bad lighting, and ancient clerical technology.

When Judy arrived there in 2004, the place had been chronically short-staffed for many years, and during her nine years working there it only got worse. The broken ringer at the lab with two loose wires sticking out was real. There’s a scene early in the first Jessie Teska book, First Cut, where a shower in the morgue locker room malfunctions disastrously. That really happened to Judy, complete with gushing water and shards of tile shrapnel.

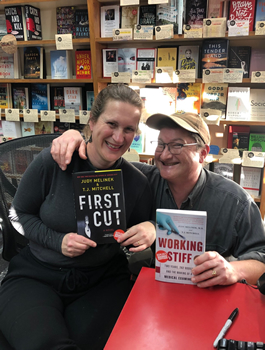

Mitchell and Melinek in conversation with journalist and comedian Faith Salie at New York City’s legendary Strand Bookstore last January

Have you ever written Jessie to stray from real coroner’s office protocols or regulations for the sake of the story?

We try to keep Jessie within the realm of what a medical examiner would actually do, but sometimes, yes, we take liberties. Never with the science, though—that’s all as real as we can make it. The way Jessie investigates at our fictional crime scenes and interviews our fictional families and witnesses also hews closely to Judy’s real experience, with methods and techniques she would use in Jessie’s shoes.

Real-life homicide detectives are not as obstructionist as the cops we have invented in our books. This is a long-cherished feature of the genre—noir mysteries would be a lot less interesting to read if the police were on the level—and a ton of fun for us to experiment with. When Jessie does break protocol, there are consequences to her choices.

Another place where we have not reflected the actual world is in the number of investigators and technical staff a doctor like Jessie would work with. To prevent overburdening readers with a rotating cast of characters, we reduced the number of morgue techs, medical examiner investigators, and ancillary police personnel. In real life, Judy works with scores of other forensic professionals every day and is constantly introducing herself to new homicide detectives at death scenes.

Melinek and Mitchell promote their debut thriller First Cut at Green Apple Books in San Francisco last January.

Have you experienced an earthquake as disastrous as the one in AFTERSHOCK?

Oh, yes! We are survivors of the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake in Los Angeles. Judy was a medical student and T. J. was a newbie working in the film industry. We lived in the West Los Angeles neighborhood of Palms, about 15 miles from the epicenter. That experience informed a lot of what happened during and after the earthquake in the book—including the eponymous aftershocks.

As we describe, during the quake it felt as if a giant had picked up our building and shook it to see what would fall out. We were tossed around the room. The freight-train roar of a big earthquake is overwhelming. We saw the blue-green flashes from exploding transformers in the sudden total darkness outside. Our character Anup Banerjee’s panicky, repeated hollering of “This is real bad!” comes right out of T. J.’s mouth from January 17, 1994, at 4:31 a.m.

We eventually left Los Angeles, moved to Boston and then New York—but then right back to earthquake country, settling in San Francisco. After 18 years there, we’ve now relocated to Wellington, New Zealand, where Judy performs coronial autopsies, and we continue to write the Jessie Teska mysteries. Turns out that Wellington is a seismically energetic city, and they have active and quite dangerous volcanoes too.

How did the name of your website—Dr. Working Stiff—come about?

Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 Bodies, and the Making of a Medical Examiner was our first book. It’s nonfiction, a memoir of Judy’s fellowship at the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner from 2001 to 2003. We moved there as a young family—T. J. as a full-time stay-at-home-dad—so Judy could train in performing autopsy death investigation under the guidance of the late Dr. Charles Hirsch, a giant of the field. There’s a tiny bit of Dr. Hirsch in Jessie’s fictional boss Dr. James Howe, but only when Howe is at his least Machiavellian and most eager to teach the science.

Judy kept a diary every day and a journal of her cases. She started work at the morgue in Manhattan in July of 2001. On September 11, she became one of the 30 doctors tasked with identifying the victims of the worst terrorist attack in our history. That terrible event was only part of her training experience, but it later pushed us to turn her diary into the book. We wanted to make sure our own kids, and the kids who would follow them, knew what Judy and her colleagues went through that day and in the weeks and months that followed.

Working Stiff isn’t a book exclusively about 9/11, though. We also reflected the everyday lived experience of autopsy death investigation. Television shows portray the job as glamorous and all about solving crimes, when being a medical examiner is really about investigating a whole range of sudden, unexpected, and violent deaths. Most of them are accidents, or things resulting from natural disease.

Working with families—counseling and comforting them on the worst day of their lives—is not at all what the public thinks Judy and her colleagues do, but it’s a crucial and rewarding aspect of their job. Judy lost her father to suicide when she was 13 years old, so she has always counseled with true sympathy the people left in the wake of a death by suicide.

Tell us something about yourselves your fans might not already know.

Judy loves art and to decompress after a day in the morgue, likes to paint and draw. She just finished a small oil painting of a tui, a native bird that makes loud and hilariously otherworldly noises in our back yard. She also molded a clay Hanukkah menorah in the shape of a waka, the sea-migration ships that brought the Maori to New Zealand, to commemorate and celebrate our first holiday season Down Under.

T. J. is a polydactylous dyscalculic. He was born with six fingers on his left hand. The extra digit had bones and intact second and third joints, but no knuckle where it connected to the rest of the hand. It just flopped around in a rubbery way off the edge of his newborn mitt, much to the consternation of his mother, who was experiencing the first of four otherwise undramatic childbirths. The finger was amputated when T. J. was two days old.

Dyscalculia is a learning disability; like dyslexia with numbers. Tell T. J. a four-digit number, and he will reverse the two middle ones. He’ll forget the whole thing in a matter of seconds, like a goldfish. He’s learned to cope with it, mostly by writing things down. Because a writer, as they say, writes.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND by Wanda M. Morris - June 27, 2024

- Sally Hepworth - May 10, 2024

- Katherine Ramsland - April 25, 2024