Africa Scene: Maaza Mengiste

Diverse, Surprising, and Superb Writing Mark New Story Collection

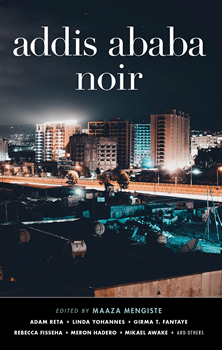

Addis Ababa Noir is another African collection from Akashic Books. And once again, it’s surprising, diverse, and contains some superb writing. The stories range widely.

Looking back to the “Red Terror” political repression campaign that followed the Ethiopian revolution sets the theme for “Ostrich,” a moving account of the time from a child’s viewpoint and another when she comes back as an adult. “Father Bread” concerns a boy, the only one spared when a pack of hyenas attacks his family. He now receives bread from a kindly man, but with shocking consequences. “Of the Poet and the Café” is about a writer who wakes one morning and finds a small change to the world—but that change leaves him unrecognised by anyone. What about a woman who sees sounds in color? Or a man unable to sleep—ever? Or a thief robbed?

This eclectic collection is edited by Maaza Mengiste, a well-known novelist and essayist from Ethiopia now living in the US. Her debut novel Beneath the Lion’s Gaze received rave reviews and prize nominations. She followed that last year with The Shadow King, which was a finalist for the Booker Prize, and was described by Salman Rushdie as “a brilliant novel…compulsively readable.” Her own story in this collection, “Of Dust and Ashes,” concerns a forensic team trying to trace disappeared people across two continents. It’s the best of a very good bunch, in my opinion.

In this exclusive interview with The Big Thrill, Mengiste shares insight into the stories and writers who have contributed to this excellent new collection.

What persuaded you to step back from your novels and edit ADDIS ABABA NOIR?

The collection offered an excellent platform to feature writing from Ethiopians who may not otherwise be known by a wider audience, not only in the West but across the continent of Africa. So when I was approached by Akashic Books, I agreed at once. I’d never edited an anthology before, and I underestimated the amount of work and time it would require—especially as I was writing The Shadow King at the same time. I really wanted to showcase these authors and make the book the best that it could be, so I read their stories, gave feedback, and edited, and it took several rounds. It took longer than we expected, but they stayed with me, and we all worked together—and it’s finally done.

The collection has a wide variety of authors—many have impressive credentials while others are less well known in the West. How did you go about selecting the authors?

First I approached authors I knew, but then I looked much more widely, not only within Ethiopia, but also elsewhere in the world. I thought it would be interesting to have those external cultural influences. That also meant I needed translators.

The backstories range widely from people murdered by the Red Terror to rural villagers who are believed to be victims of hyenas. Did you ask the authors to consider certain themes or locations, or did you leave it completely up to them? If the latter, were you surprised by the results?

Noir is not a familiar genre in Ethiopia. The country has a long literary tradition going back millennia, but most are religious texts with a message. Fiction writing is rather new. I had to explain “noir” to the writers—stories that are dark, and look at the disruption and the decaying aspects of society. The story does not have a good ending. There’s no lesson or moral at the end of it, which is what most of us grew up on in Ethiopia. Beyond that, I wanted to leave it as general as possible because I didn’t want to ruin something distinctly Ethiopian emerging. Many of the stories went back in history to the revolution. Adam Rasa wrote about people disappearing, focusing on refugees. Ghosts come into several of these stories. I found those aspects fascinating.

The backstories of the characters in ADDIS ABABA NOIR range widely from people murdered by the Red Terror to rural villagers who are believed to be victims of hyenas.

You’ve already mentioned that many of the authors live and work outside Ethiopia. Is it generally the case that it’s difficult for writers who live in Ethiopia to get recognition more widely?

Yes, especially as many of the writers work in Amharic, and that means that they need translators. I’m hoping this collection raises awareness and intrigues people.

Girma Fantaye, who is one of the writers in the collection, and I have set up an Addis Ababa literature house, and one of the things that we will be doing is to develop a series of workshops to train translators, editors, and writers, and develop a community for writers. The idea is to create an ecosystem where a community of writers can exist, and so have them be better known.

Your own story “Of Dust and Ash” is told from the viewpoints of three characters, all victims in different ways of the military dictatorships in Argentina and Ethiopia. What drew you to that topic and the cross-continent link?

I knew that the Argentinian Dirty War happened at the same time as the Ethiopian revolution, and when I looked into it, I discovered that there was an Argentinian forensics group that had traveled to Kosovo, Sarajevo, and Ethiopia to try to identify the remains of victims. I spoke to the leader of that group, and although she couldn’t tell me much about the work itself, as most of it was for court cases in Ethiopia, she directed me to materials to read. That’s when the story really crystallised. It struck me: there’s a history here that connects us, and how do we begin to talk about these stories?

Also, I knew that there was a photographer who had been held at the naval academy in Argentina and forced to take pictures of victims, and that he managed to smuggle some of them out. He survived. I thought: what if he goes to Ethiopia? I put these stories together for the fiction, but it is based on fact and research.

Several of the writers chose the theme of the Terror after the revolution. Is this a pervasive theme in Ethiopian writing?

I think it’s being written about now. Younger writers are trying to understand the effects on the older people. Perhaps their parents were in prison or were interrogated, and the traumas they experienced affected their behaviors for the rest of their lives. I kept hearing people saying that they couldn’t understand why their parents behaved in certain ways, and then as a writer you become intrigued. Adam Rasa, who had to leave Ethiopia at that time, told me, “It never leaves you.”

For a complete review of the anthology, see Michael Sears’s piece for the New York Journal of Books.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024