Up Close: Dean Koontz

Parallel Universes, Lost Loved Ones, and Evil Forces

By J. H. Bográn

By J. H. Bográn

In New York Times bestselling author Dean Koontz’s new novel ELSEWHERE, Jeffy Coltrane works hard to maintain a normal life for his daughter, Amity, after the disappearance of his wife, Michelle, seven years prior. But that façade shatters when a homeless person they refer to as Spooky Ed gives them a device that changes how they see life forevermore.

And when they accidentally discover that the mysterious object is a key to travel across parallel universes, they can’t help but wonder about finding Michelle in one of those places. But another man with a dark purpose is determined to use the device’s grand potential for profound evil.

Stories about parallel worlds have been around for a long time—ever since Hugh Everett, a physicist from Princeton, first posited the existence of a multiverse in 1957. Koontz says he enjoyed such stories, but often wished they could be a bit less over-the-top and focused more on real-world content. He never considered writing one before, though—at least not until Jeffy, Amity, and the possibility of finding the missing person of their lives popped into his head.

“Suddenly I had a very human story, real world, with the prospect of great jeopardy and all sorts of twists and turns,” he says. “It was one of those mysterious instances when I’m not trying to think of an idea for a novel, when I’m preoccupied with something that has nothing to do with writing, and I’m given a story. Sometimes, you feel you’re less the writer than a mere conduit for some cosmic writer you can’t even comprehend. It’s thrilling when it happens.”

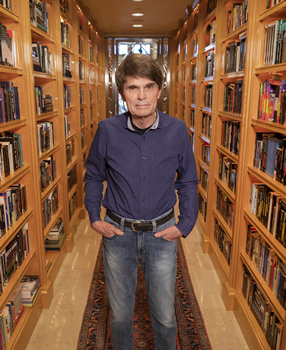

Koontz surrounded by copies of his own books in his home library. With more than 500 million copies in 38 languages sold to date, filling the shelves wasn’t much of a challenge. Photo credit: Douglas Sonders

One of the points of view in ELSEWHERE is Amity. She’s a special kid, mature for her age, and there’s always a difference in tone when we see things through her eyes.

“I love writing about kids,” Koontz says. “When I write a novel from multiple viewpoints, I always challenge myself to use the language in a different way for each character. The psycho shadow-state agent Falkirk sounds different from Jeffy, and Spooky Ed sounds different from either of them. And Amity sounds different from them all. I don’t know of a better way to snooker the reader into feeling that these are real people. If you can do that, the story acquires greater depth and resonates in a way that I don’t think is the case if the voice of the novel is always precisely that of the author, regardless of what character is center stage.”

The research that went into writing ELSEWHERE was intensive, especially about the Key to Everything and its concept.

“I could say my hobby is research,” Koontz says. “But it’s even more than that. When I’m not writing, my life is research. I read widely in the sciences, in medicine, history. And for many years I’ve been fascinated by quantum mechanics. I’ve got perhaps 200 books on that subject alone in my library. When you shovel all that diverse stuff into the furnace that is your brain, you often find that you already possess the knowledge you need to pull off a particular story.”

Although the story is relevant, Koontz is also all about the use of language, made-up words, and the actual techniques for writing.

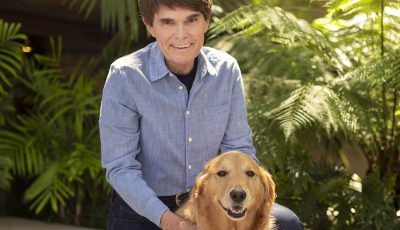

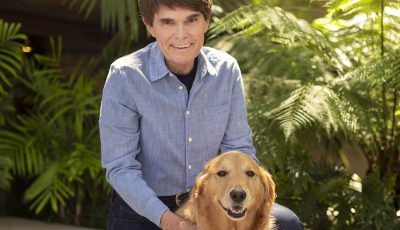

Koontz, who’s usually at his desk and writing by 6:30 a.m. every day, in his office. Photo credit: Douglas Sonders

“When I was young and stupid—the two often go together, especially in my case—I thought there were only so many tricks, techniques, that you had to learn, and that having learned them, you would find novels easier and easier to write,” he says. “What I discovered was that the tricks are infinite in number, that new ways of dealing with characters and scenes and themes continue to occur to you, and therefore you keep setting your bar higher. Writing to please yourself becomes harder, not easier—but it also becomes more satisfying.”

Some authors have used the sci-fi genre to create other worlds and critique the current world politics or realities. Koontz’s interests lay elsewhere. He’s more concerned with the human condition that remains the same across time and space and that cannot be remedied by ideology. In fact, he believes that once fiction becomes political, it stops being art, but mere propaganda.

“My politics can be summed up this way,” he says. “The individual and his or her freedom to think whatever, to fulfill his or her potential, is more important than any government, any corporation, any philosophy, any ideology; and the highest purpose of life is to seek and serve the truth, which is anathema to most politicians. Power corrupts, and writing that serves an ideology of power is itself corrupt.”

An early riser, Koontz eats breakfast by his desk after feeding and walking his dog, then works until about dinner time, at least six days a week. He’s a self-proclaimed pantser who ditches outlines.

“Storytelling is an organic process for me,” he says. “The story grows as it will; the characters take charge. I am endlessly and happily surprised by developments. I know a story is working when something a character says or thinks makes me laugh out loud, or when an emotional moment brings tears to my eyes.”

Sometimes this devotion for the art comes with a price. “When writing Intensity, I became so disturbed by the lead character’s desperate predicament that I frequently had to get up and walk around the house to work off the stress.”

As a prolific novelist, Koontz has been practicing social distancing years before it became required. However, he hasn’t yet bought into the virtual medium to replace human contact, especially when promoting books.

“Video conferencing is a medium that seems to diminish both the author and the subject, squeezing both into the dimension of a screen in ways that, for whatever reason, TV does not,” he says. “Because I’m a people person and enjoy groups of friends, this vicious bug can’t be gone soon enough.”

- Mark Greaney by José H. Bográn (VIDEO) - June 27, 2024

- Brian Andrews & Jeffrey Wilson by José H. Bográn (Video) - May 23, 2024

- Classic Thrills: THE DAY OF THE JACKAL by Frederick Forsyth - May 10, 2024