On the Cover: Scott Turow

Sandy Stern’s Last Stand

By K. L. Romo

By K. L. Romo

Defense attorney Alejandro “Sandy” Stern knows that “everything ends, of course. Life ends and thus all beforehand.” But even so, letting go is never easy.

In bestselling author Scott Turow’s newest legal thriller, THE LAST TRIAL (the 11th book of his Kindle County series), Sandy Stern will try his last case. His stellar career as a brilliant defense attorney is almost over. Never again will he argue in front of a jury or utter an objection in the courtroom.

Sandy has been a strong presence in the Kindle County legal community for more than 30 years, and a lawyer for almost 60. He knows that a criminal trial “is at heart a very nasty business to accuse, to judge, to punish. But the law, at least, seeks to ensure that a society’s wrath is not visited at random.” Now at 85, he is “withered by age and disease,” but his friend Kiril Pafko—a Nobel Prize-winning scientist for cancer research—has asked Sandy to defend him against charges of fraud, racketeering, insider trading, and murder.

Sandy realizes that his opportunity for displaying wizardry in the courtroom has almost ended, but Pafko is the doctor who kept him alive with his g-Livia cancer drug. How can Sandy refuse?

Sandy and his law-partner daughter, Marta, are closing their law practice; Pafko will be their last case. Marta isn’t sure her father can handle the stress and energy required in a murder trial, but Sandy is determined to push himself to his limit.

The dynamics of this trial are peculiar: Sandy is friends with the accused, and he and Marta have close relationships with Judge Sonny Klonsky and DA Moses Appleton. Sandy isn’t sure if these factors will help or hurt their case. Probably both.

As the trial proceeds, Sandy uncovers truths that he isn’t sure he wants to know, not only about Pafko, but also about himself. The facts highlight the value of honesty and integrity, but also enlighten Sandy about the importance of family. He’s had a dazzling legal career, but this case makes him consider: was he a good enough father? Husband? Person? In retrospect, he has his doubts.

Turow takes readers into the courtroom with Sandy Stern one last time. Pacing in front of the jury box with him, we experience both celebration and mourning for the end of his career. But as Sandy comes to acknowledge, “We are fundamentally emotional creatures. In the end, in the most consequential matters, we answer most faithfully to the heart’s cry, not the law’s.”

Before becoming a lawyer, Turow was a creative writing professor at Stanford. Here, he talks with The Big Thrill about what led him to the legal profession, insight into creating riveting characters, and how he’s used his experience as an attorney to create true-to-life legal thrillers.

You were a writer before you were a lawyer. What led you to go to law school?

In 1975 when I went to law school, I was a lecturer in the English Department at Stanford, teaching lower-level creative writing classes, after finishing my two years as a fellow there in the Stegner Program. I had never aimed to become an English professor and, although I loved my students, I didn’t find academic English a good fit for my personality. The law, on the other hand, fascinated me. I knew next to no lawyers growing up because my father was a doctor who hated lawyers long before it was routine for doctors to feel that way. When my college friends emerged from law school and began practice, I was shocked by how interesting I found what they were doing. Add to that the fact that I’d spent four years at Stanford writing a novel—I describe it as a hippie novel completed in 1974 when America was sick of hippies—that found no publishers interested, I knew I had to find another way to put bread on the table.

What led you to write the autobiographical novel One L (about your law student experience) when you were still in law school?

When I decided to go to law school, I faced the embarrassing task of explaining this career u-turn to my literary agent, who’d spent so much time trying to find a home for the hippie novel. I had every intention of continuing to write, but it sounded lame just to say that, so in the letter I wrote her, I outlined a book I wished had existed—one that described the daily experiences of law students. I was just sharing an idea and not actually proposing to write that book, but Elizabeth, my agent, showed my letter to a senior editor at G. P. Putnam’s, Ned Chase, and he wrote a contract on the spot. I went to Harvard Law School with a contract for One L in my pocket.

THE LAST TRIAL focuses on the insights “where the fragility of human nature and the justice system collide.” How often have you seen this unusual situation play out in real life?

Often. The law, especially criminal law, is about making people pay for eternal human failings. The brutal aspect of this part of the legal world I have lived in for decades is that although punishment is often justified, and may keep an individual from repeating that behavior, there is no hope that everyone will learn the intended lesson. Greed, anger, jealousy, and other deadly sins will always be with us. Criminal lawyers, both defense and prosecution, have no fear of going out of business.

Can you give us more insight into making the aging process a focal point in THE LAST TRIAL?

Sandy Stern—my sometimes alter ego—is about 15 years older than I am. But having hit 70 last year, there is no doubt that age is on my mind. So far, I’ve been blessed by good health, but I often look around a circle of friends and think, “Where did all these old guys come from?” At 70, you know you are dancing closer and closer to the edge of the cliff.

What led you to feature Sandy Stern as an aging lawyer about to retire and making his last “hurrah” in the courtroom?

Stern has been a character in virtually every novel I have published. He’s been the second banana in Presumed Innocent and Innocent, and had top billing in The Burden of Proof. But even in the other novels, he’s had a role, sometimes appearing in passing, as in Testimony, often showing up at a critical moment, as in Personal Injuries (the one exception to the rule is Ordinary Heroes, which is set principally in Europe in 1944-45, when Stern was a child in Argentina), so Stern has always been with me.

In Innocent, Sandy had cancer and appeared to be down for the count. Readers often asked me if he had passed, and I found a part of me rebelling at the notion. When I started to conceive THE LAST TRIAL, I remembered a fine Chicago defense lawyer I met while I was a federal prosecutor in Chicago, Harry Busch. He was still trying cases at 84, and more than one of my colleagues came to my office in a state of fury after Harry gave his opening statement. “Harry just told the jury that this is the last case he’ll ever try. I heard him say the same damn thing to another jury last month.”

Why did you choose to include so many different protagonists in your Kindle County series?

I wasn’t really attracted to the standard series about one character, despite enjoying so many of them, whether we’re talking about Philip Marlowe or Harry Bosch. Part of the thrill of writing a novel is drilling into a character whom I don’t know when I start. Even when I’ve let myself write about the same protagonist—Rusty in Innocent or Sandy in THE LAST TRIAL—so much time has passed that they are really different people, with so much still to discover about them.

Is there a message you’d like readers to take away from THE LAST TRIAL?

If the kernel of a book could be reduced to a few words, it wouldn’t be worth all those pages. Fiction at its heart is about conflict and ambiguity, so the precise meaning often avoids a briefer articulation.

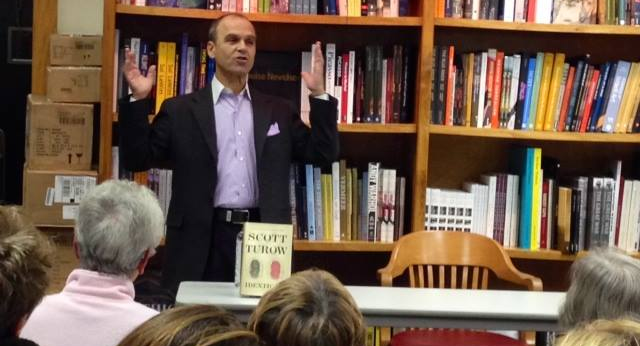

Turow receives the Sara Paretsky Award for Midwestern Crime Fiction at the Murder and Mayhem Conference in Chicago last March.

How is writing a novel like presenting a case to the jury?

Long ago, when I started writing Presumed Innocent, I realized the two processes have a great deal in common, especially from the perspective of the prosecutor I was in those days. In both enterprises—especially when you’re writing mysteries—you want to explain to an audience how something evil has happened in terms they can understand. In both instances, your story is told through the voices of many people, either witnesses or characters. And in both callings—author and lawyer—you lose if you put the given audience—readers or jurors—to sleep.

Tell us something about yourself your fans might not already know.

Something that has shocked the hell out of me is that my wife and I recently became Florida residents. For one thing, my attitude toward Florida had always been like Sandy’s, who regards the state as a prison with sunshine for America’s elderly. But about four years ago, when my wife left her job as a bank executive, we came down to Southwest Florida for a couple of months to escape the Chicago winter. The next year it was three months. Now it’s six. We will always be Chicagoans in our souls, but our time in the Midwest is divided between our city house and a place in the country in southern Wisconsin. But as far as in what state we spend the most time, we are Floridians. In fact, as the law defines it, we were last year too and just didn’t notice. For whatever reason other people make this change, I would like to state (in case J. B. Pritzker is listening) that I will continue to pay Illinois income taxes!

- The Big Thrill Recommends: WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND by Wanda M. Morris - June 27, 2024

- Sally Hepworth - May 10, 2024

- Katherine Ramsland - April 25, 2024