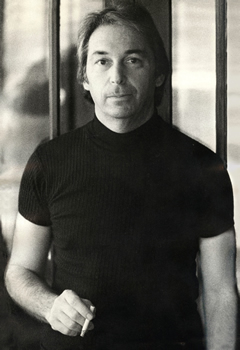

John D. MacDonald and Me by Jack Siler

By Jack Siler

By Jack Siler

I skipped my University of Illinois graduation ceremony, went to Chicago, and got married. It was a January graduation and Chicago was freezing as usual, so the honeymoon was our first trip to Florida—a week in Miami, hokum heaven, and a week in a little town of 15,000 on the Gulf of Mexico, Sarasota. It was incredible—full of painters, writers, soon-to-be-famous architects’ architecture like Paul Rudolph or Victor Lundy, a symphonic orchestra, two theaters, art films, art schools, the Ringling Museum, the wild and wonderful circus folk, and warm, welcoming people.

Sarasota was the Village, East Hampton, and Chicago’s Rush Street wrapped in exotic semi-tropics on the sea. We had a room in a little, rinky-dink motel on what National Geographic labeled one of the 10 best beaches in the world. It was. In that week we were offered jobs, a free house on the bay, and lots of friendship. Instant love. We only went back north to get our gear.

The beach was on Siesta Key, an island inside the town of Sarasota, joined by a little umbilical cord of a bridge that crossed the bay. Traffic stopped when the bridge lifted for sailboats. Siesta Key was covered with palm forest and a piece of it on the bay side had towering Cypress trees that looked as I imagined Brazil to be. I just wanted to write plays, but economic reality was calling. We got jobs.

In all of that I met almost everyone in town. Among the writers there was Eric Hodgins, who was invited to leave Fortune magazine because it wasn’t serious for the editor-in-chief of such an august publication to become publicly known as the author of a comic bestseller, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, especially since it also became a hit film with Cary Grant.

MacKinlay Kantor, who received a Pulitzer for his Civil War prison camp novel, Andersonville, also lived on Siesta Key.

As well as Joseph Hayes, apparently the sole author to write a bestselling novel—Desperate Hours—rewrite it as a hit Broadway play, and finish as the screenwriter who converted it to the film with Humphrey Bogart and Fredric March (the first of several remakes), all with smashing success.

Ad Schulberg of the incredible agent/writer/cinema family had a house on Siesta Key and her son, Budd Schulberg, author of What Makes Sammy Run and The Disenchanted, spent chunks of wintertime there too.

But in this little town where everybody knew everybody, I had one standout Siesta Key neighbor: John, yes, D. for Dann, MacDonald, who wrote thrillers, suspense, series, science fiction, and novels that were literary. John, his wife Dorothy, and their son lived in a lovely, Florida open, let-the-tree-and-sea-come-in style house on the water that was not far from ours. The house was set in deep greenery and his writing room looked over his putt-putt, outboard boat.

I’m not sure where I first met them, probably at an Art Association opening where I was on the Board or at the community theater where I acted and they came to the plays.

John was much older than me, but for some reason we struck it off. He told me that he walked into his studio at precisely 9:00 every morning and walked out at 1:00 for Dorothy’s lunch, having written 2500 words and corrected and revised the previous day’s 2500. Amazing for me, who had a radio show on the arts, a finger in every creative pie in town, and wrote at a snail’s pace—but then, I could barely imagine having the freedom to just write.

We talked about the town, writing, his subjects. I was deeply involved with the French avant-garde theater of the absurd, and he was writing the kind of books I had rarely read.

What I did find, though, was that his characters were intelligent and believable. He was very concerned with the environment and the corruption he saw in the promoter/builder people around southern Florida’s coast. That concern came bursting out in Condominium, but everywhere in his work there was an obvious intelligence and the reality of the world that came through. It wasn’t today’s mindless violence and gore. I think that’s what made John so popular, his ability to instill page-turners with a brave view of everyday corruption.

In this little everyone-knows-everyone world, there was a lunch meeting at the choice Spanish restaurant. As I recall it, it was every or every other Friday. There were usually eight or 10 of the writer crowd, 12 or 15 in the winter when the New York “regulars” came down. I had met them all, but I was still just a young, unpublished neophyte and had no place there. I also had a job. They sat around and talked books, publishing, and lots of assorted nonsense all afternoon. I couldn’t, because I worked the whole funky coast south to Naples that was being rapidly discovered by tourism.

Then I was transferred to Lakeland to manage an office in Frank Lloyd Wright’s backyard and then to Orlando, pre-Disney. After a few years away, but constantly driving back, we still considered Sarasota home. I returned to manage that office.

We built a house in a palm forest back on Siesta Key. Among the first people I looked up were John and Dorothy.

John was still the easy-going, friendly guy on the same crazy schedule: four intense work hours, then forget it. The rest of the time was for his family and friends and the business end of writing. John was on the verge of fame and fortune, but it hadn’t changed him.

I’d started writing my first full-length play.

One day he said, “Why don’t you come to the Plaza lunch on Friday?” I was awed, flabbergasted—I guess bedazzled is the word. Of course I went. Now that I ran the Sarasota branch of the company, I worked long hours and could allow myself a Friday afternoon off when the snowbirds were playing golf.

Everyone said, “Oh, you must come back, Yes, come back.” And so I became the sole un-famous, unpublished regular, the kid, still in my mid-twenties, among the veterans, thanks to John’s invitation.

Unfortunately, Sarasota’s population had multiplied times five and the season was no longer just the nice three winter months, but year-round. I had reached the top of the ladder in my field and decided to move on. I did, but single again, and I ended up in Paris, a larger version of Sarasota.

I left Sarasota just before John published the first Travis McGee book. I sometimes wonder why he placed it in Fort Lauderdale, but I suspect he smelled its success and didn’t want more people traipsing onto idyllic Siesta Key looking for him and Travis. He had already left Clearwater thanks to its tourist bloat.

Travis was a pure Sarasota kind of person, living on boats, honest, intelligent, world-traveled adventurers. We were surrounded by that kind of people as friends. Mix artists, writers, solid citizens, and some marvelously nutty ones on the Gulf of Mexico and you had Sarasota and both the content and characters of John’s books—minus the murderers. Before the skyrocket of tourists and those who made money from them it was an easy-going town of fascinating, offbeat, creative, likable people and Travis McGee would have fitted right in, right down to his environmental concerns. In that way, he was like his author.

Skip forward twenty years. I had realized that it was not feasible to write off-Broadway work and live in Paris. I had lived for three years deep in the Kenya bush and worked on a long, complex non-fiction book that didn’t work. I had been amazed one day to see a sign in a Nairobi bookstore window announcing a new John D. MacDonald book with a sign saying: “This author has sold 7,000,000 copies of his books.”

John? Good old John D.? I never imagined it would reach 10 times that.

My day job was disasters, urban reconstruction after something major. The phone rang and I was on the next plane out to some catastrophe. Four or five months of intense days of work and I left to return to Paris or wherever—and write. It seemed to me that I was at the end of my intellectual rope and I had an idea based on my work experience. A unique idea on a subject no one had ever used as a main theme. A thriller about the tight, unknown world of professional arsonists.

It took a year in LA to learn the film world and script writing. When it was done I had an agent who said an immediate “Yes!” and got it optioned, but everyone said that’s going to be a very expensive film and after the second option expired, I gave up. I’ll write it as a novel, I said to myself, then pull the script out when film rights are discussed. And, indeed I wrote the novel, and in a week it sold in a major deal to Dell.

Along the way, my editor asked if I knew anyone who might write a cover blurb. My tax attorney represented Patricia Highsmith. He was dubious that she would do a blurb, but said he’d ask. She said yes and he sent it off.

I told the editor that I had known John D. twenty years before and had no idea if he would even remember who I was. I thought it might be better if she wrote him. She did, he read it, and I ended up with two extraordinary critiques for my first novel.

For me, that was John D.—thoughtful, considerate, and generous.

TRIANGLES OF FIRE was a bestseller, no doubt, helped by the critiques.

Now, 35 years later and out of print for 27, it has never left the online used copy arena and they go out as quickly as they come in. In mid-February, TRIANGLES OF FIRE returns, revised, as part of a small Authors Guild pilot program to put certain books Back In Print.

For more about TRIANGLES OF FIRE and Jack Siler, check out his website: trianglesoffire-siler.com

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024