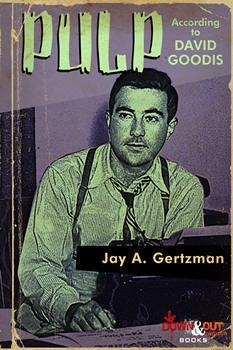

Pulp According to David Goodis by Jay A. Gertzman

PULP ACCORDING TO DAVID GOODIS starts with six characteristics of 1950s pulp noir that fascinated mass-market readers, making them wish they were the protagonist, and yet feel relief that they were not. His thrillers are set in motion by suppressed guilt, sexual frustrations, explosions of violence, and the inaccessible nature of intimacy. Extremely valuable is a gangster-infested urban setting. Uniquely, Goodis saw a still-vibrant community solidarity down there. Another contribution was sympathy for the gang boss, doomed by his very success. He dramatizes all this in the stark language of Philadelphia’s “streets of no return.”

PULP ACCORDING TO DAVID GOODIS starts with six characteristics of 1950s pulp noir that fascinated mass-market readers, making them wish they were the protagonist, and yet feel relief that they were not. His thrillers are set in motion by suppressed guilt, sexual frustrations, explosions of violence, and the inaccessible nature of intimacy. Extremely valuable is a gangster-infested urban setting. Uniquely, Goodis saw a still-vibrant community solidarity down there. Another contribution was sympathy for the gang boss, doomed by his very success. He dramatizes all this in the stark language of Philadelphia’s “streets of no return.”

The book delineates the noir profundity of the author’s work in the context of Franz Kafka’s narratives. Goodis’s precise sense of place, and painful insights about the indomitability of fate, parallel Kafka’s. Both writers mix realism, the disorienting, and the dreamlike; both dwell on obsession and entrapment; both describe the protagonist’s degeneration. Tragically, belief in obligations, especially family ones, keep independence out of reach.

Other elements covered in this critical analysis of Goodis’s work include his Hollywood script-writing career; his use of Freud, Arthur Miller, Faulkner and Hemingway; his obsession with incest; and his “noble loser’s” indomitable perseverance.

Professor Jay A. Gertzman, author of PULP ACCORDING TO DAVID GOODIS, spent some time with The Big Thrill discussing his latest work:

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

David Goodis’s characters were outcasts, hiding in cellars, flop houses, automobile graveyards or skid row alleys, all in decaying working class neighborhoods. Often, they had fallen a long way. They were beaten down and beat themselves down, but were never without the dignity of confronting the inevitable. That made them a mirror of the struggle for dignity of the working man in 1950s America. Although the stories end with the heroes still fighting themselves as well as enemies, they are still alive and therefore, despite themselves, the simple happiness of family and prideful security is vaguely possible—and deserved.

How does this book make a contribution to the genre?

It goes into more detail about the inner cities after WWII—explaining their decline thru political neglect and the appropriation of land to build highways and pollution-rich facilities. It also shows the ethnic solidarity that outlasted the decline toward racketeering and violence. That spirit of unity is lacking in suburbia and corporate life. No one goes deeper than Goodis in bringing to life the way aging residents of insecure, crime-and racketeering streets continued to provide for themselves and their neighbors. Nor does any other writer let readers see the anxiety and fear in the heart of the crime bosses who recognize how they have betrayed the people among whom they matured.

Was there anything new you discovered, or that surprised you, as you wrote this book?

Goodis’s extensive use of writers such as Hemingway, Faulkner, and especially Franz Kafka. The academically-inspired contrast between the “serious,” or “literary” writer and the mass entertainer who feeds the masses escape yarns was an accepted myth as strongly inculcated as was the false distinction between the “respected,” “professional” white collar worker and the blue collar, “under-educated” counterpart.

The two most incisive imaginative works depicting Freud’s analysis of sexual dysfunction and fear of the female are Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Goodis’s Of Tender Sin – two popular mass entertainments. Pulp noir of the 1950s is an indigenous American art form second only to jazz in power and imaginative vigor.

No spoilers, but what can you tell us about your book that we won’t find in the jacket copy or the PR material?

Goodis’s precise sense of place and painful insights about the indomitability of fate are precisely what Kafka tried to face himself. Kafka wrote, “not courage, then, but fearlessness, with its calm, open eye and stoical resolution,” in the face of the inevitable. Goodis structured Down There to end with the suffering hero’s vocation as entertainer. This parallels so carefully Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist” that I am convinced that Goodis must have read Kafka’s story very carefully.

What authors or books have influenced your career as a writer, and why?

Robert Polito’s biography of Jim Thompson, Francis Nevins’s of Cornell Woolrich, Geoffrey O’Brien’s introductions to the David Goodis novels in the Black Lizard series, the analyses of American noir by Lee Horsley, James Cawelti, and Woody Haut (three volumes). Finally, Robert Warshow’s essays on popular culture, The Immediate Experience, are as incisive as any criticism I know of.

*****

Jay A. Gertzman is Professor Emeritus of English at Mansfield University. Specializing in American publishing history, he has written books on the editions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and on the distribution and prosecution of erotic literature in the 1920s and ’30s. He is also the author of the seminal study of Samuel Roth, Samuel Roth, Infamous Modernist.

Jay A. Gertzman is Professor Emeritus of English at Mansfield University. Specializing in American publishing history, he has written books on the editions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and on the distribution and prosecution of erotic literature in the 1920s and ’30s. He is also the author of the seminal study of Samuel Roth, Samuel Roth, Infamous Modernist.

Gertzman has published articles on David Goodis in Paperback Parade, Crimespree Magazine, Academia.com, Alan Guthrie’s Noir Originals, and the programs of the Noircon conferences.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024