Africa Scene: Interview with Kwei Quartey

Corruption in High Places

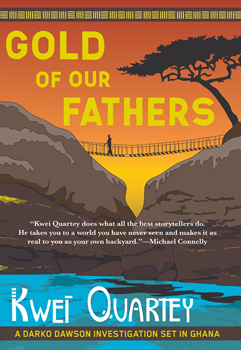

Kwei Quartey’s first book, Wife of the Gods, introduced Darko Dawson, a police detective in Accra, Ghana. Michael Connelly commented: “Kwei Quartey does what all the best storytellers do. He takes you to a world you have never seen and makes it as real to you as your own backyard.” Wife of the Gods went on to be an L.A. Times best seller. In the next novel, Darko faced a serial killer of homeless kids in Children of the Street, and the third Dawson novel – Murder at Cape Three Points – focused on the exploitation of offshore oil in Ghana.

Kwei is a medical doctor and works in Los Angeles, but he’s passionate about Ghana and spends considerable time there researching his books. His latest book, GOLD OF OUR FATHERS, was released last week, and takes Darko to a very different part of the country.

Your new novel takes place in the Ashanti region of Ghana, famous among other things for gold and beautiful abstract carvings. Gold has been a big issue in Ghana for a long time; at one stage in colonial days, the country was called the Gold Coast. Would you tell us a little about the history of the region and how that leads to the back-story of GOLD OF OUR FATHERS?

“Ashanti” is the English misnomer for the correct form Asante/Asanti, (Asa-Nti) meaning “because of wars.” The history of the Asanti people dates from the 11th century and involves numerous wars over gold, slaves, and territory. The colonial name, “Gold Coast,” and the Portuguese name mina for “the mine” (which became the present-day town of Elmina in the Central Region) underscore the importance of gold in Ghana’s history. Starting with the Portuguese in 1471, a parade of colonists tramped through Ghana, including the Dutch, Germans, Swedes, Danes and of course, the British, when the slave trade was at its peak. The words, Our Fathers, in the novel’s title, reflect the inexorable plunder by outsiders of a resource that rightfully belongs to Ghana’s heritage.

SOLID GOLD MASK, (8 X 6 INCHES) SEIZED BY THE BRITISH FROM KUMASI, GHANA, IN 1874, NOW IN WALLACE COLLECTION, LONDON

Chinese immigrants to Africa play a role in the backstory as well. Not the big engineering companies or the muscular diplomatic interventions of the government, but Chinese with a little capital undertaking illegal mining activities. How did this development come to your attention and how serious is the environmental damage it’s creating there?

The phenomenon of foreigners raiding Ghana’s resources hasn’t really ever ceased over the centuries as far back as the 15th. Around 2010, Chinese illegal miners in the tens of thousands began immigrating to the Ashanti Region in search of gold. Wanton, heart-wrenching destruction of farmlands and lush landscape took place, and conflict between the Chinese and the indigenous people resulted in cases of murder. I remember stumbling across a small online article detailing an exchange of gunfire between some Ghanaians and Chinese nationals, and then I went on to read the work by Efua Hirsch of the Guardian as she described the startling influx of gold-hungry Chinese to Ghana. I based the journalist character in my novel on Hirsch, who is of British and Ghanaian origin. So, on many levels, it has been a case of art imitating life as I selected this mining backdrop against which to set my fictional murder.

Darko Dawson is promoted to the rank of Chief Inspector, but he has to decamp and move far from home. He is interacting with a new and slovenly division and is deprived of the support of his family as well as his reliable and politically connected colleague, Chikata. Was it a deliberate decision to take him out of his comfort zone?

Yes, and not only that. It was a demonstration of how the bureaucracy of a behemoth government organization like the Ghana Police Service (GPS) can be quite family unfriendly, something that was frankly expressed to me by a police officer during one of my trips to Ghana in 2015. In western police procedurals, we often see officers posted to a comfy home somewhere with moving expenses paid, but that invariably isn’t the case in the Ghanaian counterpart. Secondly, as Darko quickly finds out, moving up in rank in the GPS doesn’t mean you get to pick and choose your postings.

There is a strong sense in the book that Kumasi is nothing like Accra. Sometimes the policemen and women have to stop the car and walk because the roads are so bad or the floods so threatening. Electricity and water work only sometimes. Did you set out to show us a very different town lifestyle in Ghana?

Yes, and also what sorts of obstacles get thrown up in the path of a detective trying to do his/her job, and what a royal pain investigation can become. Apart from Darko wrestling with electricity cuts and leaking roofs, he doesn’t have a police vehicle as we’re used to seeing in the West, autopsies aren’t done on time in a gleaming, sterile morgue, the way it’s shown in movies, and so on. Making progress with a case can be tough, and I like to show that.

Corruption in high places plays a role in GOLD OF OUR FATHERS as well. This seems almost universal in African police procedurals. Does it reflect an inevitable cultural bias?

Unfortunately, if I didn’t show corruption in Ghana, the story would not be faithful to reality. Now, whether I’m passing judgment or not is something the reader might have to decide for him/herself, but I think it’s more a personal matter to me than any formulaic approach to writing the African police procedural. My late father, a Ghanaian journalist and stickler for honesty, took a very public stance against bribery and corruption, and I think that made a deep impression on me.

There’s a lot in common between Darko and our own Assistant Superintendent Kubu in Botswana – close family life, absolute commitment to solving the case and identifying the guilty party. Do you think that too reflects a cultural approach or is it just the preference of the authors?

Maybe both? I think Chandler said something about an investigator in fiction should never be married, but you know as well as I do that being unmarried can be problematic in sub-Saharan Africa. I didn’t see Darko that way. I think in Ghana a man can go unmarried up to about 35—much younger for a woman—before people start to wonder what’s wrong with him. Marriage is much less a choice in Ghana and other African countries than it is in the West. In the Darko series, a family life renders a more valuable counterbalance to the harsh world of a police detective, as well as bringing up matters of temptation, infidelity, and the art of living with a spouse and children. In Ghana, there’s another dimension because the extended family often prevails over the nuclear. In the years I lived in Ghana, my American mother found that tough reality one of the most challenging and sometimes maddening issues to swallow as a cultural outsider. As for the other characteristics of commitment to solving the case and hunting down the guilty party, well, that’s the way it should be, isn’t it? On the other hand, the converse might make for interesting reading. Let me think about that. You might have given me an idea for a new character.

What’s next for Chief Inspector Darko Dawson?

I’m taking him even further out of his comfort zone in my next novel, By the Grace of God. In this, the fifth in the series, Darko has to face religion and his demons when someone butcher’s his wife’s cousin to death. Yes, I know your latest novel is called A Death in the Family. The parallels between your stories and mine can be quite eerie. I do have a slightly different twist, though. In Darko’s case, unlike A Death in the Family, he doesn’t want to take the case. That sets up tensions with his wife and his mother-in-law. Meanwhile, Darko’s father is progressively more demented, and Darko’s tween son is hanging around the wrong crowd. Lots of trouble on the horizon.

That’s what creates tension! I’m looking forward to it already.

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024